|

Interview

Eyes Wide Open

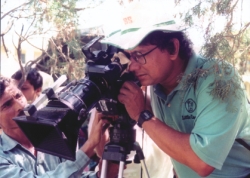

Tanvir Mokammel talks to Mustafa Zaman about the documentary he has made on the indigenous people and his fight to lift the ban that the government has slapped on it

Star Weekend Magazine (SWM): When did you first envision the film Teardrops of Karnaphuli? Star Weekend Magazine (SWM): When did you first envision the film Teardrops of Karnaphuli?

Tanvir Mokammel (TM) :Since my childhood I was fond of the stunningly beautiful nature of Chittagong Hill tracts (CHT) and the simple and friendly indigenous people of the hills. After all those bad things happened there, like many of my fellow countrymen, I too was very sad and felt that their story should be told. But because of the turmoil there it was not possible earlier to shoot in CHT and it only became a possibility after the Peace Treaty was signed.

But here I want to add that Gunter Grass, the German novelist, also had a role in it! He once said to me that we Bengali artists were not doing enough to portray the sufferings of the hill people. That discussion made my earlier resolve more firm.

SWM: You are mainly a feature film-maker, why did you choose to shoot a documentary instead of a feature film on the life of the indigenous people? What was your inspiration?

TM: I have made a few feature films but I have also made some documentaries. I normally try to make a documentary after each feature film, which I believe, brings me down from the art world of imagination, again to the everyday ground reality of our country.

Regarding inspiration, I guess, the injustice that was meted out to the hill people that had driven me to make this film.

SWM: Did you face any difficulty during filming Teardrops of Karnafuly? Did the authorities of the Hill Districts come in your way?

TM: It was not easy to move around in the trouble-ridden Chittagong Hill Tracks with a professional shooting unit. We had to remain careful. But I guess our planning was elaborate and meticulous. So we didn't have to face any harsh difficulties.

SWM: When did you complete shooting?

TM: We shot the film in two different phases in 2004. But I researched for the film for more than a year.

SWM: There must have been some sort of interaction with the people that you were filming. Was there any interesting anecdote that you still remember.

TM: During both research and shooting I had quite a few interesting interactions with the indigenous people. Let me just mention one such incident which touched me a lot. I arrived in a lonely hill just before evening. It was getting dark. So I had to stay with a Mrung family. They were very poor. Though I insisted against it they slaughtered their last chicken to serve me! I was very moved by their kindness and hospitality. I always feel a strong bond towards the indigenous people of the hills. TM: During both research and shooting I had quite a few interesting interactions with the indigenous people. Let me just mention one such incident which touched me a lot. I arrived in a lonely hill just before evening. It was getting dark. So I had to stay with a Mrung family. They were very poor. Though I insisted against it they slaughtered their last chicken to serve me! I was very moved by their kindness and hospitality. I always feel a strong bond towards the indigenous people of the hills.

SWM: What are the issues you strove to highlight in the film?

TM: The intention of the film was not to blame anyone in particular but to find a solution to the problem.

My assessment is, the greatest hindrance to have a healthy relationship between indigenous people and Bengalees is non-communication. The two parties hardly know each other. From this gulf of unknowing of each other emerges the serpent's egg. I believe, not only about Chittagong Hill Tracks, but in life in general, people will cease to hate each other if they know the other one better because then he knows his or her point of view as well. My film tried to highlight that.

SWM: Did the order of government forfeiture accompany any kind of statement that pointed out the reasons for which the film was banned?

TM: The government order of forfeiture of the film mentioned that the film contains 'objectionable comments against the national reputation and interest'! Now this is a very vague statement, and very subjective, of course. But it saddened me as it casts aspersion on my patriotism! I am not at all amused and it is rather insulting. I've made some films related to our liberation war. People of this country know me and I believe I don't have to prove anything to anybody!

SWM: Describe your best moment in the film, the portion that really made you feel at the top after you have looked at the completed work.

TM: As a film-maker it is difficult for me to point out a particular scene like that. My view may be subjective. I may be biased. But when a hill lady, while working with her crops, declares with deep sense of dignity and self-belief that 'this is my land, this is my hill. I am a hill person, why should I leave my hill? I will never leave it!' That you may say is the highest point of the film, and also the quintessence of my documentary. declares with deep sense of dignity and self-belief that 'this is my land, this is my hill. I am a hill person, why should I leave my hill? I will never leave it!' That you may say is the highest point of the film, and also the quintessence of my documentary.

SWM: How did the ban affect your morale? How do you feel about taking up any future project?

TM: It is very disheartening, I mean this kind of banning. But perhaps you know that these are not new to me. One of my documentaries "Smriti '71", about the murder of the Bengalee intellectuals by the Islamic fundamentals during our Liberation War in 1971, is still banned. Another of my feature film "The River Named Modhumoti" (also on the backdrop of 1971 Liberation War) had to undergo court cases for two years and could be released only after the High Court gave the verdict in favour of the film.

This kind of banning shows, how little civil rights or freedom of expression, we the artists of Bangladesh actually have, let alone our artistic freedom! But I don't think it will affect my future projects much. We're not the giving up type, I'll do what I've to do. I always worked like that.

SWM: Except for resorting to the highest court of the law, what other steps do you think you can take to convince the government that a ban on such a film is against the freedom of expression?

TM: The constitution of our country in Article 39 has guaranteed our right of freedom of expression. To build a democratic society it is imperative that the artists of the land should have full freedom to express themselves. Media can play a pivotal role here. No artist wants to go to court, I guess. I think if the media plays a more proactive role in upholding the rights given to us by our constitution it will work as a bulwark against the government overdoing thingslike banning a film. You have seen Michael Moore's "Fahrenheit 9/11". You have seen how sharply Moore criticized the US government, US Presidency and the US establishment. But no one in the US dared to ban the film. That should be the norm if we want to build a democratic society.

SWM: Do you think that there is a need for greater awareness among the people in Bangladesh regarding such action by the government against films, or any other creative medium?

TM: Of course, people should have greater awareness about these things. At the same time I would also like to say that people of Bangladesh should have more awareness about the ordeal of the CHT people and should have the moral courage to express it.

SWM: Tell us a little about the legal actions that you have resorted to, and also let us know about the actions, if any, by the civil society. Are you planning anything to raise a voice in favour of the freedom of expression?

TM: As you know we have obtained a verdict in favour of the film from the High Court. For that I am deeply grateful to eminent lawyer of the country Dr. Kamal Hossain and to Barrister Sara Hossain who did all the ground work. The High Court has directed the Government to show cause as to why Section 99A (according to which the film was banned) should not be held unconstitutional in violation of the fundamental right of freedom of expression. I think it is a very important legal victory. This Section 99A of the our Criminal Procedure is an undemocratic law which hangs like a Damocles's sword over the head of the artists of Bangladesh. And now with this verdict that very law has been challenged and I think the media and civil society of Bangladesh should be more vocal against this draconian law which remains as a continuous threat to creativity and creative pursuits in our country.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |