|

History

When Gandhi met Jinnah

Malabar Hill, 1944

Azizul Jalil

From the top of the Malabar Hill in Bombay we could see a wide vista of Bombay city and its seacoast. In 1979, we were visiting the park there, which had a host of animal figures cut out of hedge plants. More importantly, we passed by the house of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, which was situated on the Hill. At that time, the Pakistan High Commission in India had rented the building for its consulate-general. This was the historic building where Gandhi and Jinnah had met in 1944 for talks on the future political settlement of India.

|

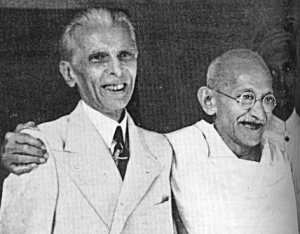

Mohammed Ali Jinnah and Mahatma Ghandhi |

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (C.R.) was a South Indian Congress leader, who later became the Governor-General of India. Popularly known as Rajaji, he proposed a 'formula' for the solution of the Hindu-Muslim problem in India. He had informed Jinnah that the plan was acceptable to Gandhi. In short, it provided for a homeland for the Muslims in the six provinces with Muslim majority, except that the bordering districts will have a vote on whether to be a part of Pakistan or India. Jinnah took Rajaji's statement with a pinch of salt - he was not convinced that Gandhi had consented to the plan, which implicitly recognised a separate state of Pakistan. On July 17, 1944, in a letter to Jinnah, Gandhi proposed a direct discussion. He wrote in their common mother tongue - Gujrati, to which Jinnah gave a gracious reply, inviting him to his house.

Hector Bolitho's book 'Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan' published in 1954 gave a vivid account of the Gandhi-Jinnah meeting. Stanley Wolpert's mammoth biography, 'Jinnah of Pakistan' published in 1981 quoted from a series of correspondence between the two giants, giving a flavour of the emotional and intellectual arguments about the future shape of India. Essentially, Jinnah wanted Pakistan on the basis of the Muslim League's Lahore resolution of March 1940, which raised the demand for Pakistan comprising of the six Muslim-majority provinces in North-East and North-West India. He persistently maintained that Muslims in India constituted a separate nation. Gandhi, while appreciating that Muslims needed special rights and guarantees, was unable to appreciate how Indian Muslims who were converts from the Indian people could be a separate nation. According to him, Muslims belonged to a separate faith but remained the same nation.

Gandhi (born 1869) and Jinnah (born 1876) grew up in the late nineteenth century. They went to England at an early age after passing their matriculation examination, which was the minimum educational requirement for admission to become a barrister. Interestingly, Jinnah, a secular minded person, had joined the Lincoln's Inn because Prophet Muhammad's name was written on its main entrance as one of the great lawgivers. Both later joined the Indian National Congress, which Jinnah left in 1921 because of disagreements with Gandhi over the non-cooperation movement.

Though there was a lot in common in their background, they could not be more different as individuals. Jinnah was a disciplinarian and believed in constitutional politics for gaining Indian independence. Gandhi, particularly after his initial South African experience of fighting against apartheid, became a mass politician, believing in a non-violent struggle against the British Imperialists. Jinnah had adopted a western style of life and preferred to remain aloof from the crowd. Gandhi, a vegetarian in loincloth led a simple ascetic life among his disciples and common people. Bolitho gave the impressions of a doctor, who treated both Jinnah and Gandhi, in terms of their personal cleanliness. To Gandhi, cleanliness was Godliness. He was scrupulously clean, yet he would perform dirty work and soil his hands, in doing some kindness for the poor people. For Jinnah, cleanliness was a personal mania. But he would not wish to touch people and wished to be immaculate and alone.

The talks started on September 9, 1944 at Jinnah's Malabar Hill house. All the face-to-face sessions were in that house. Gandhi wrote to C. R. about the first day's discussions calling it a test of his patience and reported that he told Jinnah, “I endorse Rajaji's formula and you can call it Pakistan if you like.” In the second meeting, which was also not fruitful, Gandhi reported to C.R. that Jinnah had drawn an alluring picture of democracy, claiming that it would be a perfect democracy. There were a number of other meetings, but from September 19 until the 26th, when Gandhi sent his final letter to Jinnah, the negotiations were conducted entirely through letters.

Half way through the negotiations, Gandhi had shunted Rajaji's formula and started to apply his mind to the Lahore Resolution. But he argued that the Resolution had not made any inference to the two-nation theory. According to Gandhi there was no parallel in history for a body of converts and their descendents claiming to be a nation apart from the parent stock. “If India was one nation before the advent of Islam, it must remain one in spite of the change of faith of a very large body of her children.” Jinnah maintained that Muslims and Hindus were two major nations by any definition or test of a nation and that the true welfare not only of Muslims but also of the rest of India lay in the division of India proposed in the Lahore Resolution.

They met last on September 18, but the talks did not bring them any closer. Mahatma who had started addressing Jinnah as 'Dear Quaid-e-Azam' wrote the next day “The more I think about the two-nation theory, the more alarming it appears to be. Once the principle is admitted there would be no limit to claims for cutting up India into numerous divisions, which would spell India's ruin.” In the end, Gandhi was prepared to recommend to the Congress acceptance of the Lahore Resolution but under certain conditions. These were that India would not be regarded as two or more nations, that there would be provisions for central coordination of defence, foreign affairs, customs, commerce and the like, and separate states will be formed only after India was free from foreign domination. Jinnah felt that this proposal did not concede full sovereignty to Pakistan, which he wanted before the independence of India.

Bolitho's biography of Jinnah contains interesting anecdotes about the graciousness of the two political opponents. One day at the end of their talks, Jinnah had mentioned about a rash in one of his feet. Gandhi immediately sank to the floor, had Jinnah remove his shoe and sock, held the troubled feet in his hands and said, “I know what will heal you. I shall send it tomorrow morning.” Next day a box of clay mixture arrived but Jinnah did not use it. When they met that evening for more talks, Jinnah informed Gandhi that the medicine had relieved the pain. A few days after the talks failed, Jinanh had wondered aloud in the presence of a friend: “Why did Gandhi come to see me if he had nothing better to offer?” But when the friend asked whether it was because Gandhi wanted to create public opinion against him, Jinnah said: “No, no. Gandhi was very frank with me and we had very good talks.”

Correspondence between the two went on until September 26. The day before, Jinnah had rejected Gandhi's request to be allowed to address the Muslim League session on the ground that only a member or delegate could participate in the deliberations. Jinnah admitted that he had failed to convince Gandhi about the two-nation theory, as he was hopeful of doing so. In his final letter on September 26, Gandhi stated that because of differences in their approach to the problem, the best way would be to give body to the demand as it stands in the Resolution and work it out to mutual satisfaction.

On September 26, 1944, Jinnah informed the press that he had failed in his task of converting Mr. Gandhi. Gandhi in his address to the press corps said: “The breakdown is only so-called. It is an adjournment sine die. Each of us must now talk to the public and put our viewpoints before them.” In his diary, Lord Wavell, the British Viceroy of India recorded: “I must say I expected something better. The two great mountains have met and not even a ridiculous mouse has emerged.”

Azizul Jalil writes from Washington.

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2006 |