|

Musings

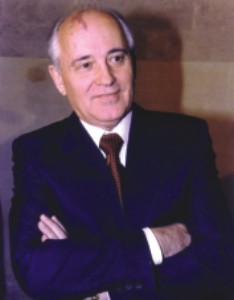

Of Gorbachev, Birth Marks and History

Syed Badrul Ahsan

On a warm summer's day in London some years ago, Mikhail Gorbachev and I engaged in a brief conversation. It was not much of a conversation, for he was the star of the show and I happened to be one of the many who had gone to watch him and hear what he had to say. No, he was no more president of the Soviet Union or general secretary of the Communist Party. At that point, power for Gorbachev had dwindled into a thing of the past. The more painful truth was that the Soviet Union he had once presided over did not exist any more. It had collapsed under its own weight, the fall having been precipitated by the glasnost and perestroika Gorbachev had initiated once he assumed charge of the superpower back in March 1985. On a warm summer's day in London some years ago, Mikhail Gorbachev and I engaged in a brief conversation. It was not much of a conversation, for he was the star of the show and I happened to be one of the many who had gone to watch him and hear what he had to say. No, he was no more president of the Soviet Union or general secretary of the Communist Party. At that point, power for Gorbachev had dwindled into a thing of the past. The more painful truth was that the Soviet Union he had once presided over did not exist any more. It had collapsed under its own weight, the fall having been precipitated by the glasnost and perestroika Gorbachev had initiated once he assumed charge of the superpower back in March 1985.

In 2003, all of that was in the past. Gorbachev was now head of a foundation he had named after himself. Politically, he was a dead duck, with opinion polls suggesting that if he were to be a candidate for the presidency of the Russian Federation, he would come by no more than one per cent of the popular vote. His wife Raisa, clearly the first Soviet political spouse to make an impression on the outside world with her grace and beauty, was dead. At home, Gorbachev was reviled by many for his contribution to the fall of communism and the death of the Soviet Union. Abroad, and especially in the West, he was predictably hailed as a man who had brought democracy to Russia. It did not matter that in the process the Soviet Union had shattered and all the evils which consumerist societies are infested with made their way into his country. In the West, he was a democrat, a media darling.

On the day I met him, media men with cameras swarmed all over the room to record all that Gorbachev had come to say. He was to speak on the issue of money laundering in Russia and what the Gorbachev Foundation meant to do about it. As he mounted the stage and took his seat, he cast a quick, surprised look at me. I was, of course, in the front row among the rest of the audience in the room. It did not take me long to understand why the former Soviet leader looked at me and then clearly stared at me. Well, the truth is that his gaze was fixed on my forehead. There was something he and I shared. He had a huge red birthmark on the right side of his forehead. I had a huge dark birthmark on the left of my forehead. That was it. For the next half an hour, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke energetically in the Russian language, with me and the others listening in on the English translation through our headphones. It was not a speech I was too keen on. I was there because I needed to see, now that I had been given an opportunity, Gorbachev up close. He had always fascinated me, particularly when he replaced Konstantin Chernenko as Soviet leader in 1985. At the end of that year, when Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan met in Geneva, it was Gorbachev who stole the show. There was a spring in his step as he walked toward the suddenly frail-looking American president. People of my generation were impressed.

Nearly twenty years after that, Gorbachev was still an impressive man. There was an eloquence in his eyes that spoke of the vibrancy in his being. He shook his head vigorously to make a point. The body language said it all. It was sad, on that day in London, to remember that a man as full of ideas, as modern as Gorbachev, had no stage remaining in the world for him to stride across, or up and down. When he finished speaking, the audience gave him a standing ovation, more for who he was than for what he had just stated. After all, when the former leader of a former superpower finds himself in the unenviable position of having to reflect on the evils of money laundering, there is not much chance he will deliver a rousing speech before you. As Gorbachev came down from the stage, I made my way to him. There was a twinkle in his eyes, enough to tell me that he looked forward to the pleasure of our getting acquainted with each other.

I offered him my hand and, as he took it, I told him it was indeed a huge pleasure meeting him. He pointed to the mark on my forehead, smiled and said something in rather brisk Russian. His interpreter told me that Gorbachev wished to know how I had got that mark and whether in some way we were not related to each other. 'Do inform Mr. Gorbachev', said I to the interpreter, 'that perhaps we are long lost cousins, that maybe a gale blew me out to the warmer regions of the world and so I had the mark on my forehead turn dark.' Once the interpreter had gone through the translation, Gorbachev exploded in laughter. We shook hands again, his one larger and stronger than mine. The twinkle in his eyes played on. In that flash of a few seconds, I thought of men like Nikita Khrushchev, Anastas Mikoyan, Leonid Brezhnev, Alexei Kosygin and Yuri Andropov. Gorbachev was unlike any one of them. He was more brilliant, more in tune with the world around him and certainly smarter. Yet they were the ones who had preserved the Soviet Union. He had destroyed it.

I walked out into the London sun thinking of the inscrutable ways in which the forces of history work. Gorbachev on that afternoon was history.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |