| Cover Story

Revisiting the Wounds of Liberation

Aasha Mehreen Amin, Srabonti Narmeen Ali, Hana Shams Ahmed and Elita Karim

The latest demand for the war criminals of our Liberation War by the people of Bangladesh to be tried and punished is evidence of the trauma and pent up outrage that the nation has been bottling up for the last 36 years over wounds that have never been allowed to heal. The agony of those who lost their loved ones to the most heinous conspiracies in our history is still overwhelming even today; there has been no solace from the pain as even after more than three decades those responsible for the murders walk freely, some even on the very soil they betrayed. It is a shame that we must collectively bear and are obligated to make amends for.

The systematic and cold-blooded abduction, torture, rape and killing of civilians from all walks of life by the Pakistani Army are a painful part of the history of our independence. What is even more irreconcilable is the fact that our own people, i.e. Bangalis joined hands with them and became collaborators of this gruesome plan to cripple a population physically, intellectually and psychologically through Nazi-like operations.

The legacy of the Pak Army -- with the help of the collaborators they thought they would maim the nation by murdering the intellectuals |

The paramilitary force Al-Badr, along with Al Shams and Razakar Bahini was formed in September 1971 under the auspices of General Niazi, chief of the Eastern Command of the Pakistan Army. Their objective was to strike panic into the people by abduction and killing. It was the military adviser to the Governor, Major General Rao Forman Ali who masterminded the whole conspiracy to extinguish the intellectuals and the higher educated class. The Al Badr paramilitary force was a special terrorist faction of the then Jamaat-e-Islami.

The collaborators helped the Pak Army to find those on their deadly list, round them up or abduct them and then take them to various places where the victims were brutally tortured and murdered. Their bodies were dumped in various killing fields, the most infamous one being the Rayerbazar Bodhobhumi (killing field) where the mutilated bodies of victims were later found. Many of the bodies were unrecognisable, some had body parts missing, while others' eyes had been gouged out. Among the victims were many intellectuals, university professors, doctors, writers and journalists. The bodies of other victims were never found. The Pak Army and their collaborators also picked up many women and young girls who were subjected to systematic rape and torture.

There is no question that such abhorrent acts against humanity have to be punished and there is more than enough international precedence to support such seeking of justice.

There is a saying that the power of the collective memory is so strong that it can pass on from generation to generation for years to come. It is usually the case that when grievous crimes have been committed against a people, somehow, somewhere along the way, the perpetrators will be punished. This is the case with soldiers from Nazi Germany, who are still paying for their crimes in World War II; or with the Korean “military comfort women” who were forced into prostitution for and by the Japanese army. The Nuremberg Trials and subsequently many other tribunals set up under UN guidelines (in former Yugoslavia and Rwanda for example) have created an international obligation to try and punish crimes against humanity especially those committed during armed conflict. Cases such as these prove that no matter how long it takes, justice will inevitably prevail. In the case of the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, however, one cannot make any guarantees. Not only did thousands of people willingly give up their lives for an independent nation, many mothers had to witness the brutal deaths of their sons, while others, to this day, did not have the comfort of burying the bodies of their loved ones. These are the people who have sacrificed their families for the birth of a free nation.

"They have made our Shahid Minar unholy." -- Ferdousi Priyobhashini |

But there was another group of people who fought an altogether different war in 1971, and the society treated this group of people quite differently. After the war ended, they did not get laurels as reward for all the pain and humiliation they endured for nine long months, nor did people welcome them with open arms when they came to their houses. On the contrary, for them, after the war ended with the Pakistanis, a very different war began. Their weapons were their self-confidence and a will to live; their foe was the complete isolation from an unforgiving society.

One such survivor is sculptor Ferdousi Priyobhashini. For many years she and her children bore the burden and stigma of being in the 'company' of the Pakistani Army, finally revealing her story in 1999 about what the Pakistani Army in collaboration with the razakars did to her, and many like her. Now 60 years old, she was just 24 when the war began and her husband left her with three children to feed and care for. She took up work at the Khulna Jute Mills as a telephone operator to make ends meet. Coming from a hard-up family it was bad enough that she had to stop her education early and get married. But her vulnerable position as a single mother made her a perfect target for the debauched Pakistani army.

Ferdousi had one encounter with a collaborator which is forever etched in her memory. While travelling by bus she describes a man with a distasteful appearance coming and sitting beside her. "I had no idea that he was a razakar. He kept asking me who I was and what I did for a living." When she refused to cooperate with him, he slapped her and threatened to kill her. The bus passengers warned her that he was an infamous razakar of the area and it would be best if she asked for 'forgiveness' from him. Ferdousi was unyielding. He pointed to the Shahid Minar and said that he had already hung a few heads there and would add hers if she didn't go with him. "To my horror when I looked over there, there really were three heads hanging from there.

"These are the razakars of 1971," says Ferdousi, "and this man was planning to take me to the Pakistani Army where he would get a reward in return for me." "These are the razakars of 1971," says Ferdousi, "and this man was planning to take me to the Pakistani Army where he would get a reward in return for me."

"I used to sit in my room and watch every day when they brought truckloads of men [freedom fighters] with black cloths on their head," says Ferdousi, "I saw one person after another being beheaded and their bodies dumped into the river.

On the pretext of being a witness to a murder the Pakistani army made her a suspect and took her for questioning several times. Each time she was raped by one or more officers of the Pak Army. The officer said she would live only if she signed a contract stating that every time a car was sent for her she would have to come in for 'questioning'.

"I didn't have the power of wealth, education, status or even age to save me," says Ferdousi, "I also had to think about my children. I had lost my sense of respect. I didn't know when the country would become independent so I sat in my room and said to myself, maybe it would be easier on me if I compromised, maybe that would make it less painful. And then when I see all these razakars freely moving around in society, I cannot explain how it makes me feel. This pain cannot be shared with anyone."

"What the razakars did at that time was seek out pretty girls from everywhere and bring them to 'serve' the army personnel. I couldn't sleep for nights, because they would appear suddenly at night to take me away.

"Everyone saw me getting in and out of the army cars and this is how rumours spread about me that I was a collaborator. There are others who have suffered even more than me," says Ferdousi, "and many people told me not to talk about my experiences because it was shameful. I found it very insulting. They tried to make me feel as if it was my fault"

They Rayerbazaar Mausoleum honours the martyred intellectuals but their murders have still not been punished

"The government should immediately arrest the war criminals," says Ferdousi, "this government has shown great proficiency in arresting. Let them show that they are capable of arresting the war criminals. The government should be a plaintiff and file the case. These razakars have committed a crime against the Bangladeshi people. We can give all the evidence we have." Ferdousi is saddened that the war criminals, right after independence, managed to make a niche for themselves. "Unfortunately none of the governments were Liberation War-minded," says Ferdousi, "and the last straw was when they were voted into parliament. There was always public debate, but the war criminals sat next to all other politicians in the parliament. How could we allow that? The biggest blow to our lives was when Golam Azam received citizenship of our country. And then when they went to Shahid Minar at midnight on the 16th of December to lay wreaths on the martyr's grave it was another shock for us. They have made the Shahid Minar unholy. We had to watch them lay wreaths there, after that what more can you possibly expect?"

Ferdousi, in her personal life, is a rebel. She had to work to feed her brothers and sisters when she was only in class 9. "The humiliation I had to endure is inexplicable, and I lost all meaning in my life. After the war when I was disgraced from all sides, I just felt like going off to a prostitute quarter. I thought that would be my only escape," says Ferdousi, "that day when I heard [Ali Ahsan] Mojaheed say those words I noticed one thing -- he could not say all these things with a straight face or look anyone in the eye. My first thoughts were -- why isn't he getting arrested straight away? If the government is sincere then they should be arrested immediately. What Mojaheed has said is like death for us [as a nation]. I have no personal enmity with Mojaheed or [Matiur Rahman] Nizami but they should answer for the crimes they have committed against the whole nation."

Journalist Selina Parveen was one of the intellectuals brutally murdered and her body dumped in the Rayerbazaar killing field

On the top landing of well-known Rabindra Sangeet singer Saadi Mohammad's house in Mohammadpur hangs a painting of a young, handsome man. This portrait, of Saadi's late father, Mohammad Salimullah, is the only likeness that the family has of him. All that Saadi's mother and her ten children have left of their father are memories. In the late 1960s Mohammadpur was an area in which both Bangalis and non-Bangalis lived. There was already an Urdu school for the non-Bangali speakers in the area and in 1966, plans were made to build a school for the Bangalis called the Mohammadpur Government High School.

Saadi Mohammad was only a schoolboy when he saw his father being stabbed and ambushed by the Pak Army |

“We were all very excited about the new school until one fine day in 1967 Fatima Jinnah landed with a helicopter in our football field and announced that the previous Urdu school would be a girls school and the new school being built would be a Urdu speaking school for the boys,” says Saadi.

After this the entire Bangali community of Mohammadpur signed a petition protesting this, and Saadi's father, being at the helm of these protests became a target for the Pakistani Army's hit list. Back in those days Saadi's house was a hub of sorts for all the Bangalis in the area. On the 25th of March, word came that the Pakistani Army was targeting Saadi's father. Saadi, a schoolboy then, remembers that they were all told to pack a bosta (sack) as they would leave the next morning. He packed a few books and a fresh change of clothes. It was the first night Saadi remembers not sleeping at all, not even for a minute. In the morning even though the driver and car were ready they could not leave because there were young boys wearing bandanas on their heads wandering around their house and keeping a watch on Saadi's family.

“I will never forget the name of the man who killed my father,” says Saadi. “I still remember which house on the para he lived in, and what he looked like and even what he was wearing that night. He was walking very slowly towards us. I was standing in such a position that I could see him coming. At first I thought he was coming for me but when he passed me by I realised that he was going for my father. I was so paralysed with fear I did not call out to my father -- whose back was turned because he was looking out of the window to find my other family members -- to warn him. The man took out a dagger and stabbed my father in the back. He dug in so deeply that it took him some time to take the dagger out before he left.

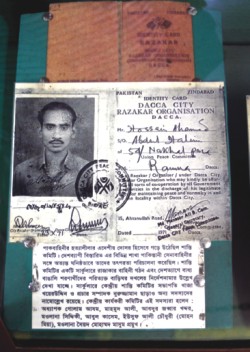

ID Card of a member of the Razakar Organisation preserved at the Liberation War Museum |

“I still remember the feel of my father's hot blood gushing out no matter how deeply I pressed his wound. At that point I actually thought he wouldn't die and tried to figure out a way to get him to safety. I took my father out on the street only to find a mob running towards us ready to kill my father. The last thing he said to me as he pushed my hands away was 'tui bach,' (save yourself) before I ran away. When I looked back I saw the entire mob ambushing him.”

After witnessing his father's murder, Saadi Mohammad and his family could not believe their ears when Shah Abdul Hannan, a former civil servant and a Jamaat-e-Islami sympathiser called Bangladesh's Liberation War a mere civil war. The very comment coming from the mouth of someone who is accustomed to undermining our people's aspiration for freedom has indeed been demeaning for the blood of the martyrs such as Saadi's father. As Hannan made his statement, Saadi's mother, who has not been able to shed a single tear since 1971, stared silently at the screen, not being able to believe the injustice shown to her family and the countless other war crime victims all over Bangladesh.

“I have no idea how these people have the courage to say such things,” says Saadi. “I just cannot understand where they get the nerve to deny what we have gone through. It shocks me to the core that they can even get away with saying this, that they have no fear of God. The Pakistani army and their supporters hacked my father to death in front of my eyes and these people have the nerve, the audacity to claim that this war was a civil war and there were no war crimes? How are they even allowed to say such things?”

For Meghna Guhathakurta, whose father was murdered by the Pak Army when she was only fifteen, her freedom is something that she guards with her life and something that she will never give up at any cost. For Meghna Guhathakurta, whose father was murdered by the Pak Army when she was only fifteen, her freedom is something that she guards with her life and something that she will never give up at any cost. |

Meghna Guhatakurta, Executive Director of Research Initiatives Bangladesh, on the other hand, is not at all surprised by Hannan's statement. Being a student of political science and international relations, she chooses to look at the situation from a more analytical perspective. “It's a very old argument that I have heard many times,” she says. “It is a view which is often expressed by the Pakistani media. Even during 1971, the Pakistani press were continuously protesting against international intervention, insisting that this was a civil war and therefore, an internal matter.

“This just proves that even after Bangladesh came into being as an independent nation, there are still many people in this country who have very Pakistani perspectives. They have not shifted from their '71 position in which they did not recognise Bangladesh as an independent nation.”

Meghna feels that the people who think this way are sitting on the fence. “I just do not think that these people should be involved in the politics of our nation. Either you acknowledge that Bangladesh is an independent nation and apologise to the nation, or openly admit that you are a Pakistani supporter. Why are they sitting in the middle, claiming that they are Bangali and denying that these crimes ever took place? The fact that we are an independent state is proof enough that these crimes did happen.”

Meghna's father, Jyotirmay Guhathakurta was a Reader (equivalent to today's Associate Professor) in the Department of English in Dhaka University. On the evening of March 25th the Pakistani army came to their flat located in a building that they shared with other university professors who lived on campus, and asked for her father. They took him out the back door of their building. At the time Meghna's family thought that they would take him to the cantonment, ask him some questions and let him go. It was only when they heard the army officers open fire that they realised that her father had been shot.

“My father was shot twice,” says Meghna. “There was one bullet in his neck and one bullet in his waist. The bullet in his waist paralysed him and the bullet in his neck hit his nerve. He was still alive and conscious when we found him in the back. He told us that they asked him his name and his religion and then came the order to shoot.”

Because of the curfew they could not take her father to the hospital and so for two days they kept him alive at home. On the 27th when the curfew was finally lifted, they took him to the hospital and the doctor said that there was no hope. He succumbed to his injuries almost five days after he was shot, on the 30th of March.

Aroma Dutta was 21-years old when the Pakistani army came to take her grandfather, Dhirendranath Datta on March 30, 1971. Datta was a Constituent Assembly member in 1948 and on February 5th of that same year he passed a motion stating that Bangla should be the official state language of Pakistan since it was the language spoken by the majority of the people in Pakistan. Aroma recalls that she was a student at Dhaka University, staying in Rokeya Hall in 1971 when her grandfather sent for her to come back to Comilla and stay with him.

“He knew that they were going to take him,” says Aroma, “but he would not leave our house claiming 'ami jei jonno ei desh chari nai ami shei jonno ei mati charbo na' (I am not leaving this land for the same reason I didn't leave this country). I still remember the night they came and took my Dadu and Kaku away. He made me read the Gita with him in the evening, and asked me to sit down. He explained that if the Pakistani army killed him in the house that we should not move his body so that the city would awaken. If they took his body, however, I would have to accept that we would never find his body. I remember not wanting to listen to him and kept asking him not to speak like that.

“As we got ready for bed I had this uncanny feeling. It was almost eerie. When the army came in the middle of the night I was still in my nightgown. Four or five officers each kept my mother and me prisoner while the rest of them took my grandfather and my uncle away. I remember one of the men taunting me, telling me to say 'Joy Bangla' in his ear. Another man hit me in the face with his torch. Then one of them came and said something and they all left. I never saw my grandfather or my uncle again.”

It was later revealed that Dhirendranath Datta, then 85, was taken to the Comilla Cantonment and tortured. They gouged his eyes out and beat him senseless before they finally killed him. Aroma returned to her home in Comilla after the war ended only to find that everything inside was burnt to ashes, and the blood of her grandfather and uncle was still on the walls. “What I cannot understand,” says Aroma, “is how we allowed this to happen. How did we, a nation that has suffered so much, come to the point that razakars and traitors are allowed to stand up in the parliament and make statements denying our history? This man denied that there was ever such a thing as muktijuddho (liberation war). He lives in our country, on the soil that we fought with tears and blood and he has the courage to say this openly. How are these people allowed to participate in the politics of our nation? They have total control over everything in our country on a state level. Bangladesh was founded fighting such oppression and yet, we find ourselves back to square one. Why have we compromised everything that we believed in and how did we get here?”

The cold-blooded murders of Bangali professionals were part of a diabolic plan to cripple a nation intellectually

Forty-eight-year old Ruksana Begum was very young at the time, but she remembers the tension in the air, the despair amongst her family members and her grandmother wailing in the next room. They had just heard that many areas in Chittagong were attacked that day and lots of men were being taken away from their homes and killed. “My family hails from Chittagong and we were all worried about my paternal uncle who was a doctor,” says Ruksana. “He had sent my aunt and cousins to the village and had stayed back himself. This was the state of many families back then. The men could not leave their workplaces, but would send their families off to safety.”

Ruksana's uncle, Shah Amin Hossain had just returned home that evening when a few men knocked on his door. “Back then, everyone was extra careful and would stay wary of everyone, including neighbours,” explains Ruksana. “Posers tricking people into coming out of their homes and informing the Pakistani army about the whereabouts of ones hidden were spreading like wildfire. According to the neighbours, two men in ordinary clothes came to pick up my uncle. They were completely helpless.” Shah Amin's body was never found. His family was stranded in the village for a while, after which they had to move from one relative's place to another, until they reached Ruksana's home in Wari, Dhaka. “My aunt was devastated,” she remembers. “But my father had lost it completely upon receiving the news about his younger brother. He stopped eating, going to work and mingling with people in the area. Eventually, my father died four months afters the death of my uncle.”

Mohsin Haroon was a toddler during the liberation war. Even though he doesn't remember anything, the stories that he has heard from his family members haunt this forty-five-year old even now. Haroon does not remember his mother, since she herself was one of the many victims of the Pakistani Army. “My maternal grandfather was the headmaster of a school in a village in Mymensingh,” he says. “Back then, it was the only well-known school where children, even from far away villages used to attend. My grandfather was a well-known teacher and was respected by the residents of the village.”

Haroon, the youngest of three, had come to live with his maternal grandfather along with his siblings and mother, since it was too dangerous to live in the city. “My father sent us to the village when one of his cousins were randomly picked up by the army and killed,” he says. Little did he know that tragedy would strike his family soon after.

In the middle of one night, there was chaos in the village. Homes were being looted and burnt, men and women were being shot dead. The Pakistani army had arrived in the village and were shooting everyone on sight. “There were many in our village at the time who would convince young men to work with the Pakistani Army and save the nation Pakistan,” says Haroon. “It was a group of these young enthusiasts who tricked my grandfather, his sister, my mother and an elderly maid servant into opening the door of the house. The army got inside, tied everyone to the chair and burnt them alive.” Two-year-old Haroon was heaped up in one corner of the house hiding with his older siblings and a young boy who used to help around in the house. Since then, Haroon's older sister, the eldest of the three, had become slightly disoriented and even now has sudden shocks. “I am thankful to God that I never saw my mother and family members burning to death in front of me,” says Haroon. “The story itself shakes me up even years after the incident.”

Remains of victims of the genocide by the Pakistani Army

and their collaborators at the Liberation War Museum

On July 20, 1973 the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act (ICA) was promulgated empowering the government to try individuals on specific crimes against humanity and peace, genocide, war crimes, violation of the Geneva Convention and international laws, for assistance or conspiracy to commit such crimes. The Act is still applicable today according to legal experts. All the government has to do is set up a tribunal under the Act and hold the trials.

There is a misconception that the general amnesty granted by the government in 1973 to the war criminals of 1971 enabled these individuals to go scot-free and be absolved of their barbaric acts. But the amnesty only applied to those who had been arrested at the time and against whom specific charges could not be made. Meanwhile all those accused with specific charges of war crimes (around 11,000) were not given amnesty but were kept in jail and their trials were to be conducted.

A Daily Star report published on November 9 of this year says that according to one of the writers of the draft, former ambassador Waliur Rahman, the ICA was initiated by Bangabandhu immediately after his return from internment in Pakistan in January 1972, and was drafted under the direct auspices of two prosecutors from the Nuremberg Trials.

The horrifying events of 1975 that deprived the nation of its leader and four of his most important ministers, that gave way to a series of intrigues and dictatorships, also paved the way for many of the incarcerated war criminals to be set free. Not only were these diabolic characters set free, they were given Bangladeshi citizenship and eventually allowed to seep into mainstream politics, thereby giving them a place of respect and eminence in a nation they had vowed to destroy. While there were many attempts from the civil society to bring the war criminals to justice, late Jahanara Imam being a forerunner in the movement, successive governments including the Awami League avoided the whole issue and even at times joined hands with them for political gain. This has been the biggest let down for the people of Bangladesh, the fact that of all the governments that followed after August 1975, not one of them showed their intention or sincerity in trying the known war criminals and stripping them of the undeserved right to take part in the governance of the country.

This explains the urgency of the present situation. People have started to hope again that under a neutral, non-political government, the reasons that kept various governments from dealing with the issue of war criminals are no longer there. The public is appealing to this government to take a positive stand on the issue, to set up a tribunal and try war criminals, both the Bangali collaborators as well as the Pakistani army personnel involved in the atrocities. It is urgent also because we still have eyewitnesses, people who can identify these criminals; their accounts will be crucial in any future trials.

We have waited 36 years to cleanse ourselves of this terrible affliction; we cannot afford to wait any longer.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |