|

A Roman Column

The Company of Women (Part 2)

Flocking and Roosting

Neeman A Sobhan

|

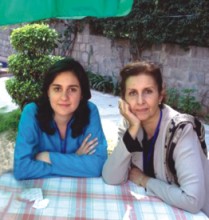

Pakistani writer Kamila Shamsie and mother, the editor, critic and writer Muneeza Shamsie. |

(I am in Delhi. It is the 20th of February, nine months ago, and the day before the start of the 3 day South Asian Women Writer's Colloquium organised by Women's WORLD, an international network of writers that address issues of gender-based censorship. In the first part of this article (SWM, Fri 2nd Nov) the writers are arriving, gathering, flocking…..) "So, I am finally meeting the writer of 'Kartography', which blew me away!" I am in the lobby of the Habitat World Hotel, Delhi, with writer Kamila Shamsie who seems visibly awkward with praise, but I tell her that it means the world to me to be meeting someone who writes with a conscience as limpid as her prose.

Last year, I came across her novel that I would have loved anyway for being located in Karachi, for me a city of childhood nostalgia now lost in the violence of politics. But her beautifully crafted narrative sprang some passages that brought tears to my eyes. I hadn't known till then that the younger generation in Pakistan could think like Kamila's characters about the present, the future and most importantly, the past:

'I am terrified, Maheen, because this country has seen what it is capable of.....yet not paused to take account, to reach inwards towards that swirling darkness and hold it up to light.

We should not have kept our name.

|

Some writers at the South-Asian Women Writer's Colloquium at Delhi. |

Pakistan died in 1971. Pakistan was a country with two wings--I have never before thought of the war in terms of that image: a wing tearing away from the body it once helped keep aloft--it was a country with a majority Bengali population and all its attendant richness of culture, history, language, topography, climate, clothing…oh, everything. How can Pakistan still be when…. the whole is gone and we are left with a part? (When we are willing to treat a part as the whole don't we fall victim to circumscribed seeing, a thing we can ill afford?) We should have recognised that the Pakistan of dreams died and was buried in the battle fields of '71……is it possible to reclaim a name?.......We act as though history can be erased….But if we allow for erasure we tell ourselves that things can be forgotten, put in the dustbin. We tell ourselves it is possible to have acts without consequences.' (page 312-313, Kartography)

I look at the youthful face of the writer before me hiding so much depth of human and political wisdom, writing with so much courage. I also think that had it not been for an organisation like Women's WORLD creating a South Asian platform, I may not have had the good fortune to meet writers like Kamila Shamsie and thank them personally for writing words that fearlessly stand for truth seeking and soul searching. The idea of translating this book to reach Bangladeshi readers plays on my mind.

As the congress of women writers proceeds over the next days the realization crystallises of how important translating is to the awareness of each others literature in a multi-lingual world, and the continuing importance of English as the link language in any cultural dialogue. This last is a matter I will dwell upon elsewhere and at length in the context of us Bangladeshis with our myopic, monolingual bias.

For the moment Kamila and I chat (our conversations will be published separately in a forthcoming article) and look forward to interacting more closely at the colloquium. The next day's opening session intrigues, titled 'Writing in a Time of Seige'. A glance at the programme had told me that there would be presentations on the theme by one writer from Nepal, Manjushree Thapa, and one from Sri-Lanka, Ameena Hussein. Manjushree Thapa's first novel, the 'Tutor of History' was also the first major English novel from Nepal. Her other book, a literary non-fiction, 'Forget Kathmandu' was a personal account of the 75 year struggle for democracy in Nepal, plus reportage from Maoist-held territories.

The Sri-Lankan Muslim name made me curious and I would grow to admire the articulate, many-faceted Ameena Hussein, not only a writer, and editor of a magazine 'Nethra', and who has produced a report on the violence against women in rural areas, 'Sometimes there is no Blood', but is also a publisher. She and her husband run Perera-Hussein Publishing dedicated to printing innovative work by South-Asian fiction writers.

I would also get a chance to hear our homegrown and controversial Taslima Nasrin; glamorous, radical Pakistani writer and filmmaker Feryal Ali Gauhar; and five Indian writers from various states and regions of India: Mamang Dai (Arunachal Pradesh) writing in English and bringing her hilly world to the rest of India through stories, poetry and a prize winning journalistic book 'Arunachal Pradesh: The Hidden Land'; Chandra Latha, soft spoken Telugu writer, who describes her riverine world of Coastal Andhra Pradesh in novels that deal with an analysis of riverscapes and water management as well as the green revolution; Mridula Garg, an award winning writer of issue oriented Hindi fiction, one of which won her the Hammet-Hellman award for courageous writing from Human Rights Watch; Esther David, who brings a neglected aspect of India's rich diversity into focus with books about her Jewish heritage; and the wonderfully feisty and courageous Gujrati writer Saroop Dhruv, whose writings, plays and involvement with relief work after the Gujarat genocide of February 2002, shows the other side of communalism---the India fighting it with compassion, justice and truth-seeking. The title of Saroop's latest collection of poems is 'Hastakshep' (Intervention) which asserts that a writer can intervene. Her play on the riverfront project and communalism 'Suno Nadi kya Kahti Hai' was censored by the Gujrati censorship board in 2005. She has just completed putting together 200 narratives based on interviews with survivors of the 2002 carnage, to be published as 'Ummeed.' She gave up writing in Gujrati as protest and turned to Hindi.

I mention her at length because we in Bangladesh need to be acquainted with such writing and acknowledge the importance of English if we are to translate these works, for example from Gujrati or Tamil into Bangla, and we also need to translate our excellent and topical writings into English if we are to make ourselves heard by our sister writers in a land not so different from our own and which affects us.

Some of the Indian writers mentioned above I would meet that very evening, at the intimate pre-colloquium dinner at India International Center; the rest I would meet the next day. I greet everyone at dinner, introduce myself and am chatting over my plate with the talented young Bengali poet from Kolkata, the lovely Mandakranta Sen with her warm smile, when in walks a lady in kurta and short cropped hair. She looks shy, vulnerable, slightly detached and vaguely familiar. Someone whispers to me, "Taslima has arrived."

(Continued next week)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |

|