| Cover Story

Rice is Life

Syed Zain Al-Mahmood

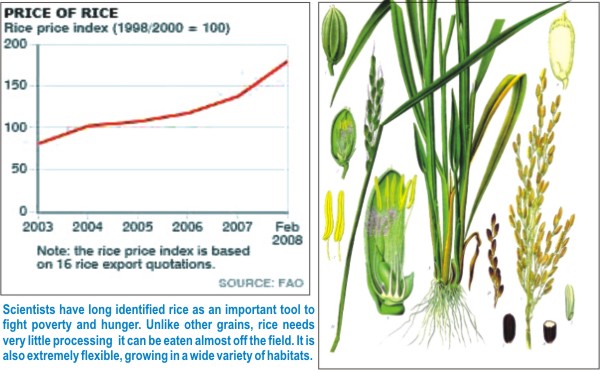

Rice is rooted in the very essence of Bangladeshi culture. Fish and Rice make a Bangali, so the saying goes. In recent times rice has made the headlines for the wrong reasons. The spiraling price of this basic staple has threatened to push millions of people into poverty and malnutrition. The growing number of middle class people queuing for subsidised rice at BDR shops showed how desperate the situation had become. To our relief, the ever-resilient Bangladeshi farmer responded with a bumper Boro crop. But the respite may be short-lived. Bizarre weather patterns, increased cost of fuel and fertiliser coupled with pressures of a rising population pose formidable challenges. Experts warn that soaring global food prices mean that we must look within to attain food security. Will Bangladeshi farmers rise to the challenge? Perhaps it is time we took a long hard look at rice.

Every day at dawn, Rustam Ali, a rice farmer, emerges from his thatched hut and makes the short trip to his two-acre plot of land. Hands on hips, the septuagenarian farmer surveys his domain. He knows the cycle of rice production as intimately as the back of his hand. It is early May and the fields are golden with rice ready to be harvested. Rustam scans the horizon anxiously for signs of storm clouds. He intends to start swinging the sickle in a day or two. A sudden thunder storm could damage the hard-earned crop. In the remote reaches of northern Sunamganj his eyes and ears are his weather service. Every day at dawn, Rustam Ali, a rice farmer, emerges from his thatched hut and makes the short trip to his two-acre plot of land. Hands on hips, the septuagenarian farmer surveys his domain. He knows the cycle of rice production as intimately as the back of his hand. It is early May and the fields are golden with rice ready to be harvested. Rustam scans the horizon anxiously for signs of storm clouds. He intends to start swinging the sickle in a day or two. A sudden thunder storm could damage the hard-earned crop. In the remote reaches of northern Sunamganj his eyes and ears are his weather service.

This year Rustam is lucky. The weather has been holding, and he knows he will take home a bumper harvest. “We got just the right amount of rain at just the right time for Boro,” says Rustam, his sun burnt face cracking into a smile. “There have been no thunder storms, no hail stone, and no flooding. Allah is kind.”

A bumper crop was badly needed. Stricken by two floods and a devastating cyclone, the country's food crisis was worsening by the day. The soaring price of rice had placed the vulnerable poor at risk of starvation. A plentiful harvest would come as welcome relief.

Bangladesh has been preoccupied with power shortages, political uncertainty and corruption scandals. But when the price of rice started to spike, it pushed everything else off the agenda. There were dark mutterings about “1974”. Surging rice prices spark primal fears among 150 million Bangladeshis. The reason for that is simple. Rice is central to our existence. When a hungry child asks for food, he says, “Ma, bhaat dao” literally “Mother, give me rice.” People in the rural areas will often eat a bowl of rice with only a pinch of pepper and fish caught from the pond. Fish and rice is not just a meal, it is a way of life. We not only get most of our calories from rice, it is also our most important economic activity. The majority of the rural population is engaged in rice cultivation. Their fortunes literally rise and fall with the success or failure of the rice crop.

Unlikely Hero: The Bangladeshi farmer Unlikely Hero: The Bangladeshi farmer

|

The rice plant takes about three months to mature. When the rice turns golden and is ready to be harvested, the paddies are completely drained and the field allowed to dry. Harvesting has several steps: cutting the plants, moving the crop to another location, threshing (separating the grain from the rest of the plant), cleaning, and storage. |

Rustam Ali's weather-beaten face tells the bitter-sweet story of rice production. Rice is a labour-intensive process and farmers like Rustam are at the mercy of the elements. Burnt by the sun, lashed by the rains, they struggle to grow a plentiful crop every year. Sunamganj is a low-lying area and floods are a fact of life. In the rainy season water stands waist deep on the plains and it is impossible to grow anything. So Rustam and his neighbours have to rely on one single crop-- the Boro. It is like a throw of the dice.

|

Rice fields cover roughly 13% of the earth's arable land. Rice

has been feeding us for over ten thousand years. In many

countries it is worshipped as a gift of the gods, while strategists

consider it a vital tool in the fight against poverty and hunger. |

Rustam Ali remembers a fateful night several summers ago. The Boro had been good that year. Rustam was expecting at least 170 maunds of rice (around 6 tonnes). His son Amjad who earned a precarious living as a construction worker in Dhaka had come home to help with the harvest. With the golden grain set to be gathered the next day, Amjad and his friends had been in high spirits. They had organised a jatra- A singing troupe had been hired. Singing and dancing was to go on throughout the night. For several days, there had been talk of heavy rains upriver in India. The river Surma had been rising, but not enough to alarm everyone. Rustam, an elderly citizen, knew better than to join in the revelry of the young men. He went to bed with the music echoing in his ears. Just before dawn, the Surma broke its banks. Rustam Ali gathered his family and neighbours rushed to the fields to try and salvage the crop. It was a losing battle. The water wiped out the crop-- and with it Rustam's hopes for the entire year.

The memory of that year and other similar ones haunts Rustam and drives him to harvest the crop as early as possible. That is why he opts for the BRRI-28 variety of rice over the BRRI-29. “BRRI-29 has a higher yield, but it matures more slowly,” explains Rustam. He prefers to play it safe.

There are no floods this year. The next day dawns bright and clear. Harvest is a joyful occasion-- the entire family joins in. Amjad is now pulling a rickshaw in the City, and is unable to come. But Rustam's wife Zarina, daughter Rabeya, and younger son Russel accompany Rustam to the field. They are joined by neighbours. The sickles swish through the air, and the reward of four months' hard work is reaped before their shining eyes.

The farmers bend down among the golden rice plants, cutting the stalk with their curved knives. “It is the result of a long and difficult process,” explains Rustam Ali, wielding the sickle with consummate skill, “First we had to till the ground and loosen it, then add fertiliser. We sow the seeds, then transplant the seedlings to the main field. Rain or shine, we have to be in the paddy field at dawn.”

|

| Women play an important role in the post-harvest activities. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

In Rustam's area most of it is done by the traditional manual method. It's back-breaking work, but Rustam Ali and his family take to it like duck to water. “It's what we do, its all we know.” says Zarina. They simply cannot imagine anything else. Deen Muhammad, a farmer in the Manirampur area of Jessore, is luckier than Rustam Ali. Unlike the farmers of the Sunamganj lowlands Deen Muhammad can grow the full three crops-- Aush, Aman and Boro. But still there are problems galore.

“It is very important that we get enough water and fertiliser,” says Deen Muhammad. “Quite often we don't get fertiliser when we need it. The government must make the distribution system work!” He, however, praises the government for ensuring smooth supply of power to run the irrigation pumps and deep tubewells. “I've heard that there are power shortages in the towns, but we have had enough electricity for irrigation. That was an important factor in the bumper harvest.”

Deen Muhammad is well-off by rural standards. But small-scale farmers often struggle to find the money to buy fertilisers and pay for tractors and “shallow pumps”. They have to borrow money or sell their crop in advance to pump owners at low prices. As a result, they don't reap the rewards of their labour.

Despite the hardship, however, the mood is upbeat this year. “We are getting good prices,” says Deen Muhammad with a smile. And that is always an incentive to do better.

The threshed rice is loaded onto trucks, and hauled away to large “boilers” for milling. At the rice boiler mill, the golden rice is spread out in the yard to dry. The rice that we eat is actually the grain that is found inside the seed hull. During milling, the hull or outside layer is removed, leaving brown rice. White rice is the result of more processing that removes the outer layers of bran until it is a translucent white grain.

|

| Drying the rice husks. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

When the price of rice almost doubled this year, it caused demonstrations and riots from Haiti to Indonesia to Burkina Faso. It's a stark reminder of how important rice is to the global population. Indeed, this semi-aquatic grass has been feeding us for more than ten thousand years. Chinese records of rice cultivation date back 4,000 years. Evidence has been found of similarly ancient rice plantations in the Korat area of Thailand. But perhaps the oldest record of domesticated rice (15,000 years old) was found by archaeologists in Korea. A staggering 120,000 varieties of rice are known to exist worldwide. 4 billion people depend on it for sustenance. For many nations rice has a deep socio-religious significance. In India, rice is associated with prosperity and with the Hindu Goddess of Wealth, Lakshmi. In Japan, it is said that the first cultivator of rice was the Sun Goddess Amatereshu-Omi-Kami. She grew rice in the fields of heaven, giving the first harvest to Prince Ninigi. In Thailand, it is believed that, like a mother who feeds her children, the rice goddess Mae Posop gives her body and soul to sustain human life.

According to estimates, Bangladeshi farmers have produced around 19 million tonnes of Boro rice this season. As the Boro hits the market, the prices of rice at city shops have leveled off. Fears of a famine have receded. But prices will still remain high, experts warn. This is a global trend and it may mark the end of the cheap food era. There is a worldwide food price hike and cheap imports to supplement domestic production may no longer be an option for Bangladesh. We have to grow more rice to feed our 150 million mouths. Indeed, with a little effort, we could become rice exporters. In this changed scenario, agriculture often dismissed as unfashionable assumes renewed importance, and the Rustam Alis of Bangladesh may be cast in the role of unlikely heroes.

|

Experts warn that the price of rice will remain high. Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

A lot of research has gone into developing high-yield varieties of rice that are able to withstand different weather conditions. At the forefront of this effort is the International Rice Research Institute based in the Philippines. Established in 1960 by the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations in cooperation with the Philippine government, IRRI developed the high-yielding, short-stemmed rice varieties that sparked what became known as the Green Revolution in rice. “This is estimated to have saved millions of Asians from famine and provided a platform for the region's subsequent economic growth, which lifted more people out of poverty than at any other time in recorded history,” says the Institute's website. To Bob Ziegler, plant pathologist and director of IRRI, rice is a powerful engine that can drive away poverty and hunger.

A pivotal moment in the study of rice to alleviate poverty came when scientists decoded the rice genome. In 2002, researchers from the University of Washington and China cracked the genetic code of rice. And then in December 2004, the International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (IRGSP), a consortium of publicly funded laboratories completed the sequencing of the rice genome. The high-quality and map-based sequence of the entire genome is now available in public databases.

The results have been swift. The genetic information has speeded up the breeding of tougher and higher-yielding varieties. Scientists are developing rice that can be “packed with vitamins” to fight malnutrition. Researchers at the University of Tokyo have created a strain of rice that carries a vaccine for cholera.

High hopes are pinned on 'flood-proof rice' developed in 2007 by IRRI. Scientist Dave Mackill and his team discovered a gene that allows rice to 'hold its breath' underwater for up to two weeks. It's called the submergence 1 gene sub-1 for short. This waterproof rice could bring hope to farmers like Rustam Ali Mondol who live in flood-prone areas. Flooding is one of the main reasons of crop failure in Bangladesh. The rice type, called Swarna Submergence 1, has done very well in trials in Bangladesh and elsewhere. “It's a spectacular demonstration of the power of science to make a difference in people's lives," says Robert Ziegler.

|

| Husking the paddy(left). The silver lining of the current crisis could be that climbing food prices could be an incentive for farmers to grow more rice (right). Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

The role of science in the cultivation of rice is easily apparent. 75% of rice strains being cultivated today have been developed as a direct result of scientific research-- not counting genetically modified (GM) crops. The average Bangladeshi farmer may be illiterate, but they are at the cutting edge when it comes to rice production thanks to the efforts of the government and non-government agencies working in this sector. Speaking to farmers like Rustam Ali and Deen Muhammad, it is surprising how well informed they are. They speak about the latest high-yielding varieties of rice and the current methods of using fertiliser with easy familiarity. They are truly part of the Green Revolution.

|

Farmers take home a bumper harvest. |

The Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the world in the seventies and eighties, and dramatically increased food production. Many strategists thought the food problem had been solved. Food fell off the agenda as aid agencies focused on issues like health and education. Experts were caught unawares by the sudden surge in food prices in the last few months. There had been an upward trend in recent years, but from June 2007 to May 2008, rice prices almost doubled. The results were far reaching. Food riots erupted in Cameroon, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia and other countries. In Pakistan and Thailand troops were deployed to prevent the looting of food from fields and warehouses while the Sri Lankan government threatened to use force against rice hoarders.

“A silent tsunami that knows no borders sweeping the world,” is how Josette Sheeran, head of the UN's World Food Programme, described the current global food crisis.

|

| Photo: Zahedul I Khan |

But what has caused the food crunch? It's probably a combination of factors: higher energy and fertiliser costs, greater global demand especially from emerging middle classes in China and India, extreme weather especially cyclones in South Asia and droughts in Australia, loss of farmland to bio-fuel plantations, price speculation etc.

Some experts are also pointing the finger at bad policies. The World Bank and IMF are at the forefront of the new economic orthodoxy that tells us to cut subsidies and open up markets. In many developing countries the WB-IMF prescription has hit agriculture hard. Farmers in developing countries like Bangladesh are poor, and can ill afford to buy fertiliser and power at international rates. Without government protection, external investment or subsidies, small-scale farmers are unable to produce the required food.

The food versus fuel debate is another topic guaranteed to provoke fist-fights among strategists. Biofuels are all the rage these days 'green' energy created for a cleaner environment. The most important biofuels are ethanol - produced from corn or sugarcane and bio-diesel derived from vegetable oil. Critics have attacked bio-fuel production saying it is taking over land needed for growing food and pushing up prices. The UN's independent expert on the right to food, Jean Ziegler called bio-fuels a “crime against humanity” and called for a moratorium on their production.

“The US currently grows one-sixth of its grain harvest for cars, which is madness," another expert commented. "It is perfectly possible for the world to feed itself, but it depends on how we are growing food. If we continue to grow crops to feed cars rather than people, we're in trouble." Supporters of bio-fuel are fighting back. Ecologist David Tilman pointed out that the way forward should be to grow inedible bio-fuel crops on otherwise unproductive farmland.

|

The threshed rice is loaded onto trucks, and hauled away to large “boilers” for milling. At the rice boiler mill, the golden rice is spread out in the yard to dry. The rice that we eat is actually the grain that is found inside the seed hull. During milling, the hull or outside layer is removed, leaving brown rice. White rice is the result of more processing that removes the outer layers of bran until it is a translucent white grain. |

One thing is certain. High food prices are here to stay for a while at least. But the crisis may be more of a price problem than a supply problem. The worry therefore is not so much famine as widespread social unrest and malnutrition. Research has shown a direct correlation between rice prices and nutrition in Bangladesh. For example, surveys found that a 20% fall in the price of rice increased household consumption of rice by 38%, as well as other foods such as milk, meat, and eggs. Overall calorie consumption improved on average by 12% (10% for adults, 20% for children under 5 according to an IFPRI survey 1991-1992) Conversely, a sharp increase in the price of our basic staple would see people cutting back on meals to make ends meet. In a country like Bangladesh, where most people spend 70% of their income on food, it is impossible to cope without consuming less. Unless of course, incomes rise to keep pace with the price hike.

There could be a silver lining in the current food crisis. The ultimate remedy for high price is high price. Climbing food prices could be an incentive for farmers to grow more rice and we could see a supply response. And the government could be forced to try to achieve self sufficiency in food. Bangladesh will probably produce about 38 million metric tonnes of rice this year. That would still leave a shortfall of around 10% -- roughly 3 million tonnes. We must close the gap. Bangladesh produces more rice than Thailand-- the world's biggest exporter but we consume more. If we can increase production and dare we say it diversify our diet, we could be in the premier league of rice exporters.

|

L-R: Rice production is often a family business.

Golden Carpet: Rice is spread out to dry at the boiler mill. |

|

| With the harvest over, there isn't much else to do except fish. |

In this era of food shortages and high prices, “those who have food are going to have a big edge,” suggests Donald Coxe, global portfolio strategist at BMO Financial Group. With a bit of prudence and a pinch of luck, Bangladesh could be one of those countries.

Back in Tahirpur, Sunamganj, Rustam Ali Mondol has completed the harvest. A fat haystack stands in the middle of the yard a monument to the bumper Boro. Rustam Ali surveys the golden grain with satisfaction. He is not aware of the goings on in the global market, but he is pleasantly conscious of a job well done. He can spend time fishing during the next few months. But as soon as the water recedes in November, he will be back in the paddy fields planting seed. The cycle of rice will start all over again.

Photographs: Syed Zain Al-Mahmood Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |