| Cover Story

Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kraft |

The Power of the Handloom

Judging from the choking traffic at any point of the day, it is clear that shopping for Eid has already begun. As the countdown to Eid-ul-Fitr kicks off, hordes of people hit the shopping malls, street shops and the many different bazaars all over the country. Buying new clothes being a major part of the Eid and coinciding Puja celebrations, the market for trendy clothes could not get any busier.

Elita Karim

But there seems to be a change in the way consumers are behaving these days. The urge to establish one's cultural and national identity has resulted in many Bangladeshis being enamoured by local products. It is not just patriotism that is making people buy Bangladeshi clothes; it is the high quality of local fabrics that are making people wakeup and pay attention. Designers of top fashion houses have been experimenting with local fabrics, blending different genres of local material, combining them with various techniques in stitching or embroidery, to develop unique textures, patterns to create comfortable, durable and chic clothes.

Bangladesh has gone through several changes in the last few years. With the telecom sector and the multinationals influencing a good part of the economic and social being of the country, the young men and women have also developed new ideologies where fashion, trends and ‘looking good’ is concerned. The days of scavenging the shops for the exact copy of the black chiffon worn by an Indian actress in a Bollywood Blockbuster or loosening one’s wrath on the tailor for not possessing the ability to ditto the cut on the kameez collar seen on some famous television series on Star Plus, are slowly fading away. Individual styles are developing. The crowd today, especially the young generation of trendsetters, are looking for something more original.

“When I was younger I had to go with what my mother would choose for me on every Eid,” says 37-year-old Fashion Consultant of a buying house, Priyanka Iqbal. “They were mostly ready-made Pakistani three pieces and Indian saris once I got older. Even my casual wardrobe consisted of imported clothes, which would be bought from the local stores in Dhaka. But now, it is very refreshing to see young college students and professionals wearing stylish clothes made in Bangladesh.” A glance at the streets of Dhaka City, and one will find both students and the working people wearing short kurtas, fotuas, churidars with short shirt-collar kameezes, and colourful scarves over shirts and jeans, and jazz them up a little with beads, bandanas, jute bags, casual sandals and clay jewellery. The get-up is trendy, reasonably priced, refreshing and Bangladeshi.

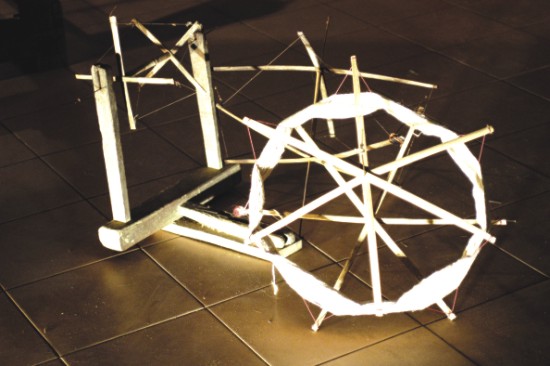

While the material maybe used for contemporary fashion, the fabric is made in the most traditional way. Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kraft.

Over the last few years, the country has been witnessing a spectacular growth in the garments sector. With the implementation of the compliance law in the year 2004 / 2006, this sector is now all the more well equipped compared to the drastic conditions of even half a decade ago. This, along with the fact that people’s idea of fashion is slowly changing with time, has been an important factor behind the sudden re-emergence of the textile and the cottage industry.

The arduous art of weaving. Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kra |

Local fabrics such as jamdani, different kinds of silk, Tangail cotton and silks, kantha stitched material and so on, are finding their way into the most coveted designer wear and being displayed with much grandeur on the ramps. Experimentation with fabrics has also become a popular phenomenon with discerning designers who are eager to establish their exclusivity through new blends and patterns in the material they use to create fashion. The result is a wide variety of local fabrics that have unique textures and designs, luring the consumer and ensuring an enduring fan following that is unlikely to dwindle.

Behind this slow revolution, however, are the weavers of Bangladesh, remarkably skilled, creative artisans who spend gruelling hours on the loom to create patterns with mathematical precision. Khaled Mamud, the director of Kay Kraft, a famous name in the boutique industry, which recently completed fifteen years, elaborates that it is a long and drawn out process that goes behind each kind of fabric.

There are eight major weaving pockets in the country, namely Chapainawabganj, Tangail, Narsinghdi, Rangamati, Manikganj, Comilla, Sirajganj and Narayanganj. “Believe it or not, but each region boasts its own signature where producing fabric and cutting threads are concerned,” says Khaled. Plenty of experiments are being done with the threads from these weaving pockets to produce new materials, he adds. “For years, Rangamati has been producing a material which was hard and very rough,” says Khaled. “The people there were used to it. But then we spoke to the weavers and worked with them on making the fabric a little softer. They did that and now the particular fabric is very popular amongst the locals of Rangamati.” There are two ways to produce fabrics. One  would be to create a new line of material and the other would be to experiment and work on the existing material and develop it. One of the most popular materials in this part of the world was muslin, which, according to Khaled, is not produced anymore. “The muslin clothes that we get now are not actually pure muslin,” he says. “We used to get the pure ones decades ago. It is a shame and a mystery how the muslin industry simply closed down. If the production of the material had continued, we would have made a mark in the world market for sure.” Where technology develops with time, the mystery of disappearance of the muslin clearly breaks that rule. would be to create a new line of material and the other would be to experiment and work on the existing material and develop it. One of the most popular materials in this part of the world was muslin, which, according to Khaled, is not produced anymore. “The muslin clothes that we get now are not actually pure muslin,” he says. “We used to get the pure ones decades ago. It is a shame and a mystery how the muslin industry simply closed down. If the production of the material had continued, we would have made a mark in the world market for sure.” Where technology develops with time, the mystery of disappearance of the muslin clearly breaks that rule.

Nevertheless, a variety of fabrics has been developed, fused with silk and cotton. A simple fabric is made with weaving the threads together. However, what defines the fabric is the way the thread has been cut itself, generally categorised under 'thick and thin'. The way a thread is cut and a fabric is designed define the thoughts and ideas of the weaving pockets situated in eight different areas of Bangladesh. “We usually have a very wrong idea of what the khadi fabric is,” says Khaled. “We tend to think that khadi is made with cotton threads cut thick and is always very warm. That explains the huge sale of khadi clothings and products over the last few years when Eid would coincide with the winter season. The khadi clothes were actually made thick and warm keeping the season in mind.”Khadi is a handloom, or a fabric which is handmade. In fact, it is handmade right from scratch. “Even the thread used to make the fabric is hand made from the cotton or silk,” says Khaled. “It does not necessarily have to be cotton. It can also be silk.”

Bangladeshi fabrics have taken the ramps by storm.

Photo credit: Zahedul I Khan. |

Yet another very popular fabric made in Bangladesh is the endy. Khaled says that in the last few years, his team has been experimenting with endy. “Initially, the endy material used to have a very earthy colour, now we have managed to develop several shades and types of endy materials,” he says. Initially it was very difficult to dye the threads on an endy material. For quite some time then, fortuas and shirts would come in shades of two basic colours instead of one. “A handloom or a machine made cloth is weaved on two levels, horizontally and vertically,” says Khaled. “There was a time when we would dye the fabric as a whole once it was produced, but then we decided to dye the threads instead to get the complete feel. The problem was that we could not dye the threads on both the levels. We would either dye the thread weaved horizontally or vertically, but never both. Thus, many of our products would come in basic shades of white and blue, brown and maroon or blue and brown.” The endy also went through another change when the designers decided to take off a

Handlooms used to make trendy casuals.

Photo credit: Zahedul I Khan |

stitch after every block on the fabric, thus creating a checked design. “We used to do this on print at one time,” says Khaled. “That was so much easier. But working on it with threads was more challenging and had a different essence to it all together.” Other experiments have resulted in products fused with khadi-silk, cotton silk, endy-cotton and much more.

With the fashion industry changing rapidly, a lot of western fashion are now being fused with deshi styles. In fact, garments such as trousers, shirts, vests are made with Bangladeshi fabric. Well-known designer Bibi Russell very recently launched her first outlet in Dhanmondi Road 27, which flaunts such a set of fusion of the traditional and western. One of the ideas that trendsetters would not like to miss out on is the line of jeans that she has created with Bangladeshi fabric.

For those who prefer to follow the conventions, boutique houses and big outlets in the country have created a series of churidar kameezes, colourful punjabis, fotuas and saris. Munira Emdad, Handloom Developer and also the proprietor of Tangail Shari Kuthir says that she has been working on bringing back the ancient designs in Jamdani. “I have noticed that there are a few designers who have introduced new designs for Jamdani saris,” she says. “People seem to like this experiment and are accepting this trend very well. But I don’t like it very much myself. There are thousands of elegant ancient designs which are getting lost and I think they should be revived instead.” Yet another project that Munira has been working for a long time is recreating the original Mirpuri Benarasi sari. “This is quite difficult since the original Benarasi sari takes a long time to make, and is handmade just like a Jamdani sari,” she says. “Each design is unique and consists of intricate work done by the weavers.”

A lot of these mixes are also seen in Aarong products, a pioneer in bringing together the deshi weavers and bringing their skills in front of the world. Their products include saris, fotuas, punjabis, kameezes and other products like satranjis, carpets, bags and much more. Aarong constantly tries to mix silk and cotton, khadi and cotton and even produce their own version of muslin.

|

| A model displays a new design of a locally made sari. Photo credit: Zahedul I Khan. |

A traditional jamdani>, always in fashion (top); making the basic raw material -thread (below). Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kraft. |

Natural dye fabrics continue to be trend setters in the market and a fashion house such as Arannya has been relentlessly perfecting this technique on handlooms, creating subtle hues and shades that cannot be achieved by synthetic dyes. Reviving the ancient art of indigo and other vegetable dyes on dramatic silks or comfortable cottons has made a major breakthrough in the market for authentic, Bangladeshi garments.

|

| The golden hues of silk thread. Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kraft |

|

The fabrics made in Bangladesh are unique and trendy. Local handloom fabrics, are better looking than synthetics, more comfortable and have the added appeal of being hand-made. However, competing with the massive foreign market prevailing in the country, the Bangladeshi market still takes a back seat. “We do have ways to improve this situation,” says Khaled. “Firstly, the customers should know how a fabric is made. If the benefits and the advantages of buying Bangladeshi products, along with the knowledge of how the basic fabric has been made are communicated to the customers, I am sure that many customers would be eager to purchase handloom fabrics. Secondly, the government must implement a law which actually exists in the country, which is, no foreign goods can enter the borders without paying the proper tax amount. I know of many such instances when even zero tax is paid on such products. If these border laws are brought under control, the situation will improve, but slightly.”

Showing off the richness and versatility of Bangladeshi silk. Photo credit: Zahedul I Khan

For fashion aficionados, always on the look out for something new, the development of local fabrics is welcome news. It means that designers have more material, literally speaking, to experiment with and create clothes that are not desperate copies of Bollywood fashion, but originals that set their own trend. In order to make sure that this kind of development of local fabrics continues, we as consumers have a responsibility to try to consciously buy Bangladeshi products when we think of going shopping. Supporting this industry will not only boost the demand for Bangladeshi fabrics locally but internationally too.

Made in Bangladesh

Locally made Products can make the Dream of Autarky come True

Ahmede Hussain

Photo credit: Imtiaz Ahmed Dulu / Kay Kraft.

Abandoned by her parents, twelve-year-old Masuma sleeps under the awning of a foreign bank, the latest to enter the country’s burgeoning capital market. Masuma does not know how to read and write, neither has she learnt the hidden laws of probability, according to which the stock exchanges work. She sells flowers at the intersection in Motijheel, near the DSE, as it is called by those who invest in the share market. She has remained outside the steady growth of 5/6 percent that Bangladesh’s economy has enjoyed over the last few years. Her father left them, she and her mother, in 2005, the year in which Bangladesh was listed with South Korea and nine other countries as ‘Next Eleven’, eleven emerging economies, by Goldman Sachs investment bank. Her mother ‘disappeared’, as she calls it now, a year after that. Her mother has got married again, Masuma found out later. Left with no other option, Masuma, barely in her teens, started to beg; with the hundreds that she had saved, Masuma bought a few bouquets of flowers to sell it to the commuters who halted at the crossway. Since then it has been her only source of income; “It’s better than begging,” she, who goes hungry on every alternate days, says proudly.

Over the last couple of decades Bangladesh’s economy, considered the 48th largest in terms of its total Gross Domestic Product, has grown. It is difficult to tell to what extent locally made products are contributing to its overall growth, but the advent of Bangladeshi consumer products has become one of its prime contributors. People belonging to the middle-income group are flexing their financial muscle, generating an ever-increasing demand.

The irony, however, does not escape us: Bangladesh’s booming economy is based on a system that forces its own children to go hungry year in and year out. Millions live on subsistence income; hundreds and thousands of children grow up stunted and malnourished. The law of capitalist economy requires growth and development to be heterogeneous-- while new shopping malls are being built and are quickly crowded with the overfed rich, jostling over gaudy, glitzy expensive clothes; we still have to live with the sight of famished, bone-all Masumas sleeping in the footpath. In this cruel city of over one crore, they are the silent, invisible majority. The path to free them from the clutches of the double-headed monster of poverty and exploitation remains a long and treacherous one.

“The boom has taken place because of the small and medium enterprises (SME), the growth of the garment industry and the remittance sent from abroad by migrant workers,” says MM Akash, economist and teacher of Dhaka University. The consumers of these locally made products belong to the lower and middle classes, who, he says, if are given proper government help, can work wonders. One reason why the SMEs have flourished in the country is because certain import restrictions are in force. “All the SMEs produce goods and commodities are import substituting, or they supply the raw materials to small agro-based industries,” he says. If these small enterprises are given the driver’s seat, they will generate more growth and the benefit of it will trickle down to the bottom. “The government should make bank loans cheap and easy for local small industries. It must also create cooperatives of small farmers and weavers and the government has to take the responsibility of marketing their products so that middlemen like big retail stores cannot exploit them,” Akash says.

Jamdani - a glamorous, traditional trademark of Bangladesh.

Photo credit - Zahedul I Khan

In fact in an economy like ours cooperatives and guilds owned by the farmers and small investors are necessary to relieve the burden of import expenditure. As their produces are primarily import substituting, encouraging their growth will mean more employment opportunities, which for its turn will generate demand.

Akash has made scathing remarks on the outlets that buy products from small producers only to sell it at a higher price. “They add value to the products that the poor weavers produce and market them at a higher price,” he says, “In the long run this process leaves the producers exploited.” He thinks it is high time that these outlets give up its ownership to the weavers and small producers who produce all its products. “Grameen Check is owned by the weavers, if Grameen can do it, why will other such organisations will remain an exception?”

To strengthen the growth and sustainability that our economy has been enjoying over the last couple of years, the government must take concentrated steps. One wrong decision can ruin everything. “If now,” Akash says, “the government lifts the restrictions following some dictums of the World Bank and open our market to cheap substandard Chinese goods, our SME-based growth, which has so far grown steadily, will not sustain.” Inflow of remittances, on the other hand, does not go to the productive sector. The government can take certain measures that will increase non-resident investments.

Taking the right steps in the right direction to sustain the demand for Bangladeshi products can be the first step towards autarky. It means that Masuma's freedom from hunger and poverty is entwined with Bangladesh’s economic independence.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008

|