|

Documentary

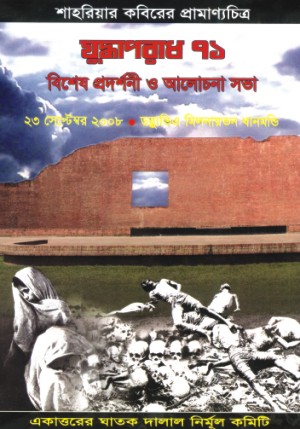

'71 at SOAS

Kajalie Shehreen Islam, in London

It was one of the many events which take place at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London every day. People from all over the world, along with British citizens and SOAS and other British university faculty, from Asia, Africa and the Middle East to the Americas come to SOAS to share their knowledge, relate their experiences and drum up support for different causes. Be it the state of women in occupied Iraq or political crimes in Asia, at a place as diverse at SOAS where in a class of 20 there will be people of 15 different nationalities, everything has a keen audience. Last Tuesday, they -- people from the school, students and faculty, from the city, Bangladeshis and non-Bangladeshis alike -- gathered at the Khalili Lecture Theatre to watch a documentary on war crimes in Bangladesh in 1971.

Shahriar Kabir's 'War Crimes 71' on the atrocities committed by the Pakistani army and more so the collaborators during the Liberation War had the audience at SOAS rooted to their seats. Some were shocked at the violent birth of a country they had never even heard about before, others gasped at the shot of a dog pulling at a rotting body while others cried at the stories of women violated during the war.

The documentary, however, was not an eye-opener only for non-Bangladeshis. With interviews of various members of the Razakar group claiming to have taken orders from Moitta Razakar (Motiur Rahman Nizami), it was difficult even for Bangladeshis to fathom how he and others like Ali Ahsan Mujahid now claim that there are no war criminals in Bangladesh, how they served as ministers in past governments and how they still continue to roam free in a country they tried so hard to stop from being born.

Members of the Razakar Bahini, recruited with promises of work and a steady income and who were later jailed for being collaborators or whose throats were slit by the Muktijoddhas, demanded the punishment of the leaders under whom they had served and who have so far gotten away with impunity. Women who were violated during the war, not even accepted by their parents after the tragedies, demanded the punishment of their violators. Several Pakistanis interviewed in the documentary -- poets, journalists, activists, some of whom were also harassed, jailed or ostracised for supporting the Bangali cause in 1971 -- all demanded the punishment of the war criminals, both Bangladeshi and Pakistani, and sought forgiveness from the people of Bangladesh.

In the panel discussion and question-answer session which followed and which was attended by Shahrir Kabir himself, a faculty of Pakistan Studies at Lahore University requested a copy of the film for his institution for, according to him, the whole episode has been wiped out from the history books in Pakistan and needs to be known. Among the panel discussants, chief guest Lord Eric Avebury of the House of Lords suggested that people in Britain form a group to drum up support -- logistical, legal, financial and moral -- for the cause in order to make the people of Bangladesh know that they are not alone in their battle for justice. In answer to a question from the audience he also said that two prominent war criminals who are in Britain can legally be extradited to Bangladesh if and when the courts in the home country make an application once the trial process starts. Abbas Faiz of Amnesty International noted that the failure to seek justice for the war crimes in Bangladesh has encouraged 'a persistent nature of impunity' in the country and that an official inquiry must be carried out along with the normal judicial process to bring the culprits to book. Irfan al Alawi of the Centre for Islamic Pluralism pointed out the role of Saudi Arabia in funding Islamic militant groups around the world and their links to the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan and the Jamaat-e-Islami in Bangladesh and that in order to counter these the supply of funds must be cut off. The discussants as well as members of the audience belonging to the probashi community in Britain also noted the significance of the upcoming elections and that the political parties contesting the elections should promise to take up the cause and follow it through when they come to power.

The film and the discussion which followed made it quite clear that the demand for the trial of war criminals in Bangladesh is neither an unreasonable, unrealistic nor unfeasible one. Several brave witnesses remain who are willing to testify against the culprits. With the support of the people not only at home but also from the international community, it is possible and indeed necessary that the war criminals be brought to book. Trial of the war criminals would finally mean closure for their victims, not only those who have suffered directly at their hands, but also the nation as a whole which they have wronged. People around the world realise this; what the people of Bangladesh and the leaders they vote to power do about it remains to be seen.

.Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2008 |

|