|

| Much has been made of how the employment of women in the garments industry is challenging traditional social norms, and rightly so. |

Food for Thought

Challenging Complacency

Farah Ghuznavi

As far Bangladesh has come in recent decades in its progress towards a fair deal for its senior citizens, we still have a long way to go. A cursory look at socio-economic indicators such as ownership of assets and access to higher education tell a fairly straightforward story in this regard. As do the everyday examples of violence suffered by women that so poignantly feature on the pages of our newspapers, day after day. So I am always fascinated (and invariably appalled) when I hear people dismiss current levels of discrimination against women in Bangladesh as being relatively minor, or not sufficiently important to be an issue requiring immediate action. There are many arguments (excuses?) used to justify such perspectives; sometimes these rationales are even offered in good faith. But that does not make it any less important to analyse and challenge such views.

For example, one reason offered for not taking immediate action in favour of greater equality between women and men takes the perspective that the necessary social changes leading to such equality are already underway as a result of wider social processes, and will go ahead regardless of what we do. That is an attractive possibility, and certainly frees us of the responsibility to look at our behaviour and examine our attitudes more carefully! But is it an accurate assessment?

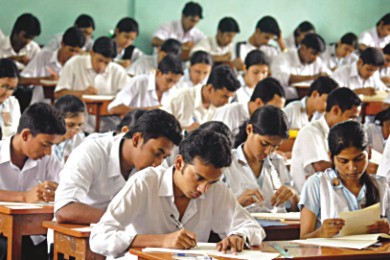

It is undoubtedly true that society in Bangladesh is experiencing a transition from being a predominantly agrarian economy to becoming one that is moving towards greater industrialisation. Those changes are well underway, with their resultant social implications for the status of women. One of the most evident changes has been the growing presence of women on the streets of Dhaka. Much has been made of how the employment of women in the garments industry is challenging traditional social norms, and rightly so. Not only has the creation of these jobs meant an unforeseen and quietly revolutionary presence for women in a public space that was previously the exclusive domain of their male counterparts, but the impact of these new employment opportunities has percolated well beyond the urban centres into the rural heartland of Bangladesh.

|

| In the urban centres of the country, a basic commitment to women's education has been in place for longer than it has in the countryside. |

What was previously unimaginable-- a rural woman, often unmarried, living without a male “guardian” in a city like Dhaka-- has become if not commonplace, then at least a widely recognised phenomenon, acknowledged even in the wilds of the countryside; after all, that is where a large number of those making up this new urban workforce originally hail from. Sometimes for the sake of respectability, families may choose to make up the existence of a fictional guardian or family member in the city, with whom their daughters are staying, but that does not take away from the changed realities on the ground. And notwithstanding the fact that many of the so-called “garments girls” face poor working conditions, social prejudice and various forms of exploitation in their new environment, these jobs have also given them an unprecedented degree of personal and financial independence; and along with it, some degree of social manoeuvrability.

Thanks in a large part to the efforts of NGOs like BRAC, the importance of educating girls has also taken hold at the village level in Bangladesh. Today, despite valid concerns about security and limited financial resources, there are few rural parents who will admit to supporting the idea that girl children don't need an education. That is a very big change from the situation that existed just two decades ago. Despite the almost inevitable shortfall in allocations and flawed implementation, government policies have also played their part in promoting girl's access to primary and (to a more limited extent) secondary education, and should be given credit accordingly.

In the urban centres of the country, a basic commitment to women's education has been in place for longer than it has in the countryside. There we have also seen social change taking place as a small number of increasingly visible young women manage to progress into tertiary education. Once again, this reflects some differences in attitude. Parents who are otherwise socially conservative have started to allow their daughters to leave a home in order to pursue higher education opportunities in other places, notably the capital city, Dhaka.

Many of these bright and hardworking young women then manage, often against the odds, to obtain coveted jobs in the private sector, in a range of organisations providing banking, telecommunication and other services. To get these jobs, these women have to establish a space for themselves in a highly male-dominated environment; yet increasing numbers of them are doing so. And they are making progress within their chosen fields, addressing a range of challenges-- from openly sexist attitudes among their colleagues, to more subtle forms of discrimination such as the withholding of promotions or having to accept it when senior colleagues, often male, take credit for their work. The latter situation can take place in the life of anyone, male or female, but men are likely to put up a stronger fight against such exploitation because they have been brought up with a stronger sense of entitlement in this society.

So my point is this: our society is undoubtedly a state of transition, and as a result social changes are also taking place. But these changes - particularly ones that are beneficial to the status of women - cannot be taken for granted. If we look at the growth of the garments industry it becomes clear that workers, both male and female, have been most benefited when policy measures or activist support have enabled them to negotiate a better deal for themselves. Indeed it has been seen that employers sometimes prefer to hire women precisely because they are perceived as having a weaker negotiating position than their male peers, and having a preference for avoiding trouble. So without support and intervention from garments activists, it is questionable how far the employment alone would have empowered or changed the lives of the women workers, in particular. As periodic unrest at the factories indicates, industrial employment without sufficient regulation is rarely an unmixed blessing.

Finally, if we look at the other changes I have mentioned, it is clear that many of them have arisen out of intentional policies. Whether it is the government's attempts to improve girls' access to education, or the efforts of NGOs and individuals to raise social and parental awareness about the importance of sending girls to school (and their provision of the necessary educational services to enable parents to do so), none of this has come about by a happy coincidence. It has required hard work, strategic thinking and considerable commitment to get this far and it will require an equal amount of those things, if we are to continue to make progress. So let's dump the denial, and tell it like it is.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |