Musings

The Legacy of Murder and Mayhem

Syed Badrul Ahsan

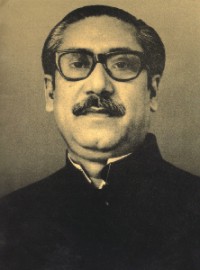

It is a bizarre legacy we are heir to, here in Bangladesh. You could call it a burden that we have borne for years. But, of course, now that the Supreme Court has decided that the murderers of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman deserve no pity and are privy to no mercy, we as a nation can tell ourselves that there is light after all at the end of what has been a long, deep tunnel. It is not, mind you, the prospect of the execution of the assassins of the Father of the Nation we look forward to. No one gloats over the spectacle of a man's death. But everyone celebrates the return of sanity in life, be it individual or collective. It is a bizarre legacy we are heir to, here in Bangladesh. You could call it a burden that we have borne for years. But, of course, now that the Supreme Court has decided that the murderers of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman deserve no pity and are privy to no mercy, we as a nation can tell ourselves that there is light after all at the end of what has been a long, deep tunnel. It is not, mind you, the prospect of the execution of the assassins of the Father of the Nation we look forward to. No one gloats over the spectacle of a man's death. But everyone celebrates the return of sanity in life, be it individual or collective.

If you recall, what occurred in the pre-dawn hours of August 15 1975 was but a precursor to all the evil, manifest and increasingly more macabre in its dimensions, that was to be. For the Bengali nation, such evil was not supposed to be. Indeed, an overriding purpose behind the emergence of Bangladesh as a free state in 1971 was the creation of an egalitarian society that would be a pronounced departure from what had gone before. And that, as you remember, was the increasing militarisation of the state of Pakistan through perceptible and relentless denials of democracy to its people. The rise of Bangladesh out of the ashes of East Pakistan was in essence a pledge in defence of a new order, one that would be secular and democratic in outlook and that would in turn inaugurate a new spring-dappled dawn for Bengalis.

The assassination of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman put paid to that lofty expectation. And then it did something more. It served as the inauguration of what would in time come to be identified as the pre-eminence of anti-constitutional politics, based on murder and mayhem, in the country. That violence could serve as a means toward a removal of elected government was the lesson we went through in August 1975. It was a lesson buttressed by the murder, along with the killing of Bangabandhu, of nearly his entire family. The president's chief of security, Colonel Jamiluddin Ahmed, was not spared. He died at the approach to the road leading to Bangabandhu's home.

August 1975 ought to have been the beginning and end of anti-politics. It was not, for a couple of reasons. The first was the decreeing of the infamous indemnity ordinance guaranteeing the protection of Bangabandhu's killers from future prosecution. That was shame of an unprecedented sort, for never before in the annals of history had the murder of a head of state and that too the creator of a country been given legal sanction. The shame only went up in intensity and dimension when Bangladesh's first military dictator, General Ziaur Rahman, made sure that Parliament, elected under his patronage in February 1979, ratified the ordinance and incorporated it in the Fifth Amendment to the constitution. And the second? It was in the mischief of the killers making their way to Dhaka central jail on November 3 1975, barely three months after Bangabandhu's assassination, and shooting the four leaders of the Mujibnagar government dead. It was not mischief any more. It had become moral outrage; and it would lengthen itself into bigger outrage three days later, on November 7. Khaled Musharraf and his junior colleagues in the army were done to death in gruesome manner. And not a soul raised the question of who killed them or what were the elements behind their tragic end.

The deaths of Musharraf, Huda and Haider were a new manifestation of the entrenchment of murder and illegitimacy in national politics. Indeed, between August and November 1975 it was more than politics that came under threat. It was the state which tottered on the brink of collapse. Observe what was to follow. In his five years as Bangladesh's military strongman, Ziaur Rahman went through no fewer than eighteen assassination attempts before biting the dust on the nineteenth. And the Zia legacy? It took off through the murder of Khaled Musharraf; it made sure that history was put in a straitjacket through an airbrushing of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, of Mujibnagar, out of national history. If Bangladesh's history has been undermined, has been abused, it was the Zia regime that did it all. If p olitics is today a tenuous affair, you need to mull over the ramifications of the so-called Bangladeshi nationalism that first found expression through Khondokar Abdul Hamid in February 1976. olitics is today a tenuous affair, you need to mull over the ramifications of the so-called Bangladeshi nationalism that first found expression through Khondokar Abdul Hamid in February 1976.

The images of historical distortion, the overturning of secular democratic politics --- all of that is what has spilled over on to our social landscape. The revolt by men in the air force in 1977 led to the execution of hundreds of soldiers, on Zia's watch. And there were other soldiers who died on the gallows every time a coup against Zia turned abortive. The climax, if you can see it that way, came through Zia's assassination on 30 May 1981. Should that have been the end of tragedy? Let the answer be. But do not forget that thirteen officers paid with their lives for that presidential murder. You do not know if they were guilty. But you do know that they were tried in dubious circumstances and hanged in precipitate manner. General M.A. Manzoor was already dead, through a bullet in the head. No one has ever explained that sorry end.

And when General Ershad seized power on March 24 1982, it was proof again of the preponderance of unconstitutional means in national politics. It was one more link in the chain of bad destiny. It would not stop in 1990. Observe the ferocity with which fifty seven army officers were assassinated at Peelkhana in February this year.

It is that destiny we seek to overturn today. For reasons that are as historically profound as they are morally uplifting.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |