Endeavour

Highway to Hell

Syed Zain Al-mahmood

What did former finance minister M Saifur Rahman, poet Mominul Mauzdin, and fruit vendor Absar Mia have in common? They were all killed recently in road crashes on the same stretch of the Dhaka-Sylhet highway.

The manner of the crashes varied. Saifur Rahman died when his SUV went off the road trying to avoid a goat and landed in a ditch. Mominul Mauzdin's car was crushed following a head-on collision with a speeding bus. Absar Mia was run over by a truck while trying to cross the road in front of his home. But the fatal crashes follow a common pattern -- they are part of a growing toll of death and injury on the Dhaka-Sylhet highway since the road was upgraded at the beginning of the century. Experts say they illustrate the fact that “better roads” are not necessarily safer. Traditional road design aimed to reduce the number of crashes by widening and straightening roads. But that has no impact on the rate of death and disability because people simply start to drive faster.

Almost unnoticed, the problem has assumed epidemic proportions. The Dhaka-Sylhet road, also known as Highway N2, may not be the most deadly road in Bangladesh. According to anecdotal evidence and crash data, Dhaka-Chittagong and Dhaka-Aricha roads are much more dangerous. Overall, Bangladesh has some of the most treacherous roads in the world. Road accident statistics show that the fatality rate in Bangladesh is nearly 100 deaths per 10,000 registered motor vehicles per year. Although the official figure for road deaths in Bangladesh is three to four thousand a year, independent studies by international agencies such as the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) have suggested the actual death toll in Bangladesh could be three times as high.

The number of people seriously injured in road crashes in Bangladesh is estimated at around 1,00,000 each year. It is an appalling price to pay. Even if we leave aside for a moment the emotional trauma suffered by the family and friends of victims, the economic burden in itself is staggering. It is estimated that road crashes cost Bangladesh roughly 2 per cent of GDP every year.

The iRAP methodology calls for forgiving roads that can reduce the number and severity of crashes.

Although there is a consensus among politicians, policy makers and the public that road traffic injury is a major problem and that something needs to be done about it, opinion varies widely regarding which approach to take. Road safety experts have over the past two decades adopted a systems approach to road traffic injury prevention. This comprehensive approach takes into account the interaction of three factors -- human, vehicle and environment during three phases of a crash event: pre-crash, crash and post-crash. Implementation of the “safe systems” model has brought significant reduction in levels of traffic-related death and injury in many countries, including some developing ones.

“Today's systems assume that humans don't make mistakes. One mistake and you might be killed,” says road safety expert Greg Smith. “But roads should be engineered in such a way that even if the driver loses control, the infrastructure should be able to mitigate the seriousness of the crash. It's all about kinetic energy control.”

But there has been no way to scientifically measure the safety of roads -- until recently. The International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP) has assessed millions of kilometres of roads all over the world in the past five years and aims to significantly reduce road casualties by improving the safety of road infrastructure. iRAP targets high-risk roads where large numbers of people are killed and seriously injured, and inspects them to identify where affordable programmes of safety engineering can reduce road traffic injury.

At the invitation of the Ministry of Communications, iRAP has started a pilot project in Bangladesh, and the first highway to be assessed is the Dhaka-Sylhet highway. Greg Smith, who is leading the iRAP team, says the iRAP survey tries to identify design flaws from the standpoint of road safety and suggest simple but effective countermeasures.

“You could be in the safest car, obeying traffic laws and wearing a seatbelt and still be injured in a road traffic crash,” says Smith, “if the road you are driving on induces mistakes. The good news is that this can usually be corrected quickly and cheaply.”

The iRAP team uses a special survey vehicle that takes a “snapshot” of the road every 100 metres. The drive-through inspections involve a continuous record of road infrastructure elements, including pavement condition, road markings, pedestrian footpaths, over-bridges and roadside hazards.

“We don't want gold-plated roads,” says Greg Smith, who is regional director, Asia-Pacific of iRAP. “With a scientific approach, sometimes a coat of white paint will save lives.”

Out on the road, the iRAP way quickly becomes clear. Greg is quick to point out design flaws that could lead to high risk situations. “This road was upgraded with funding by the World Bank,” he says. “More could have been done to incorporate safety into the design. Look, how the pavement was laid on top of the old road. This has created a ledge where a tire could go, causing the driver to lose control.”

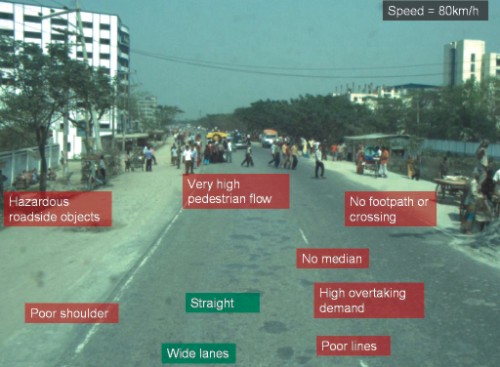

In the course of his work with iRAP Greg has seen some dangerous roads, but he admits that the Dhaka-Sylhet highway is right up there with the most treacherous. “There is a mix of fast and slow traffic, leading to very high overtaking demand. There is no median barrier in most areas, which increases the risk of frontal collisions. When you take into account the high pedestrian flow across the road, you can see that it is a disaster waiting to happen.”

On a straight stretch of road Greg nods with approval at the smooth surface and clear lines. “The lane width is good,” he says. “But in this area you can see that there are roadside hazards like trees. A barrier along the side would prevent injury here.”

With the adoption of the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety, road traffic injury has been recognised as a public health and sustainable development problem.

Greg Smith is at pains to explain that the requisite research, technology and expertise to save lives already exists. Road safety engineering makes a direct contribution to the reduction of road death and injury. Countermeasures can often involve little more than adopting modern signing, hazard markings and junction layouts. Well designed intersections, safe roadsides and appropriate road cross-sections can significantly decrease the risk of a crash occurring and the severity of crashes that do occur. Dedicated footpaths and bicycle paths can substantially cut the risk that pedestrians and cyclists will be killed or injured by avoiding the need for them to mix with motorised vehicles. Dedicated lanes for motorcyclists can minimise the risk of death and injury for this class of road user.

The data collected by the survey vehicle will be analysed to produce a Star Ratings system which will provide a simple and objective measure of the level of safety provided by the road's design. The iRAP team will then produce a Safer Roads Investment Plan drawing on approximately 70 proven road improvement options to generate affordable and economically sound infrastructure options for saving lives.

The plan which iRAP calls 'Vaccines for Roads' expects high investment returns -- for each pilot country the estimated benefit to cost ratio of the recommended programme is greater than 10. In Malaysia for example an investment of US $180m is expected to deliver US $3bn in benefits and prevent over 30,000 deaths and serious injuries over 20 years.

“We know how people are killed, and what can be done to stop it,” says Greg Smith. “For example, we know that foot over-bridges reduce pedestrian deaths by 90 per cent; we know road safety barriers reduce runoff deaths by 90 per cent; we know a central median divider reduces deaths due to frontal collisions by 90 per cent. All we need is the political will to implement these countermeasures.”

The iRAP survey targets high-risk roads and suggests simple but effective counter measures.

At a time when many policy makers still think road deaths are an inevitable by-product of motorisation, iRAP is telling governments that they don't have to trade safety for mobility. With the recent proclamation by the United Nations that 2011-2020 will be the Decade of Action for Road Safety, road traffic injury is sure to move up the global political agenda. It may finally be time to reclaim our roads.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009 |