|

Cover Story Cover Story

An Artist of Exceptional Versatility

Aasha Mehreen Amin

The art of the pioneers of Bangladeshi artists has been an extravaganza of the colours, shapes, rythmn and emotions of the heart of rural life, hence the use of luscious landscapes and folk motifs in many of their canvases. For the artists and mentors and their adoring students, depicting nature had more than just aesthetic value; it was a political statement to establish one's identity and empathy for the common man. For an artist like Qayyum Chowdhury who was part of the great art movement that hit Dhaka in the 50s as well as all subsequent political movements, nature and the common man has always been the driving force behind his work. Mentored by the maestro Zainul Abedin who established the first art school in Dhaka and inspired by the stalwarts around him, some of them teachers, some of them classmates, Qayyum Chowdhury pursued his passion during the most exciting stage of the art movement. Yet it has been his God-given gift and a mind seeped in cultural richness that has made him one of the most significant artists of our time. His works are often full of optimism and emotion. Versatile and contemporary, Chowdhury continues to enthrall his audience by constantly reinventing himself as an artist, never failing to delight.

Many of his early works are characterised by neat compositions that are thematically based on rural lifestyle but treated with a contemporary flavour using geometric shapes and lines. His depiction of the traditional mahajan (money lender) an oil on canvas done in 1956 is remarkable in its details and treatment, the checks in the lungi, the creases in the starched white kurta and prayer cap, the hand fan near his feet are given a different dimension through the sharp, straight lines. 'Boat in the moonlight' (1956) has the familiar balance and sharpness as well as the realistic imagery made dreamlike through watercolour that dominated his earlier works. A lithograph called 'village woman', a favourite subject for the artist, on the other hand, shows the beginnings of Chowdhury's knack for creating perfectly balanced collages, often a trademark of his book covers for which he is well known. The maiden is the centre of everything in this piece but there are many semi-hidden images to discover--eyes peering out of the darkness, tiny figures, faces, an animal giving a multi-layered aspect to the piece. About a decade later, the figures turn more abstract and have that distinctive pattern-like quality as in ‘Banana Grove’ (oil on masonite, 1966), a cluster of shapes with no spaces, only sections in perfectly blended shades.

In the 70s, Qayyum's work takes a new turn, influenced and involved as he was in the political movements of the time. A spectacular oil on canvas named '7th March, 1971' captures the spirit of revolution in a glorious design of festive colours -- blues, reds, yellows and greens. It is a tight composition full of symbols, the elongated shapes represent the oars of boatmen interspersed with the original green, yellow and red flag of Bangladesh. The painting is one of hope and excitement--a transitional point that will change lives forever. In 'Protest', a work done after the war of independence, again the countless oars are present but this time held by more pronounced figures, the colours are more muted enhancing the sombre expressions of the faces. Qayyum's artistic sensitivity to the turbulence around him recurs in 'Bangladesh 71' (oil on canvas, 1972) representing the genocide of '71, the anguish, terror and destruction is shown through darker shades and chaotic imagery. In the 70s, Qayyum's work takes a new turn, influenced and involved as he was in the political movements of the time. A spectacular oil on canvas named '7th March, 1971' captures the spirit of revolution in a glorious design of festive colours -- blues, reds, yellows and greens. It is a tight composition full of symbols, the elongated shapes represent the oars of boatmen interspersed with the original green, yellow and red flag of Bangladesh. The painting is one of hope and excitement--a transitional point that will change lives forever. In 'Protest', a work done after the war of independence, again the countless oars are present but this time held by more pronounced figures, the colours are more muted enhancing the sombre expressions of the faces. Qayyum's artistic sensitivity to the turbulence around him recurs in 'Bangladesh 71' (oil on canvas, 1972) representing the genocide of '71, the anguish, terror and destruction is shown through darker shades and chaotic imagery.

“During the Pakistan period, artists felt constrained”, says Qayyum, “Creative people have always been a little left-leaning and feel for the ordinary people. After Liberation, the canvases of all artists suddenly became brighter.”

Qayyum's artistic beginnings make for a fascinating story, more so because it was a time of transition for Bengalis both culturally and politically. Born on March 9, 1932 in a small township called Feni and growing into a shy, reticent adolescent it would have been unlikely that he would take up art both as a passion and calling. Then again, with a father who was a voracious reader and lover of music, creativity was always encouraged in the household. Qayyum's father, Abdul Quddus Chowdhury came from a landlord family that had lost its wealth but retained its attachment to culture. His eldest paternal uncle Mohtasambillah Chowdhury was a writer. Another uncle, Aminul Islam Chowdhury, was a writer and wrote a historical treatise on Noakhali. With the family moving from place to place according to where his father would be transferred, Qayyum got a first hand experience of rural Bengal which would greatly influence the themes of his art work all throughout life. The artist's father, Inspector of Cooperatives had an impressive collection of books and music records; he also regularly subscribed to major literary journals such as Prabashi, Bharatbarsha and Bangashree. Thus Qayyum developed an avid interest in reading, music and of course, art.

“Often there would be reproductions of paintings in these journals which I avidly read,” says Qayyum Chowdhury, “and I would try to copy them.

“My father had gone to college with K. S. Barman and so loved music. We had a gramophone and every day he would sing along with it to make my little sister fall asleep. All this affected me. Today I have a very good collection of music. I always listen to music when I work, it is part of my life.”

Qayyum believes that all creative processes must work together in art. “When I look at a picture,” he says, “I try to see whether there is anything lyrical in it, whether there is music or poetry. Music, as you know, can be interpreted through colour. My personal opinion is that an assimilation of all these elements are necessary to bring about the depth in an artist. When these elements are missing, I feel the artist has not matured.” Thus the lyrical quality in Qayyum's works all throughout the decades, whether it is a vibrant depiction of gypsies in oil, women combing hair in gouache or the simple lines of a drawing in pen and ink.

|

| Waterfront, Watercolour, 1958. |

Whether by coincidence or fate, by the time Qayyum took his matriculation exams he was living in Aqua Mymensingh where his father was posted and which was the home district of Zainul Abedin, an artist who had dreams of opening an art school in Dhaka. Qayyum's older brother and Zainul's younger brother were classmates and the latter suggested that Qayyum go and see Zainul Abedin when he would come for a visit. It was in fact his father who first took the shy teenaged Qayyum to see the master. After flipping through the drawings and paintings of the nervous teenager, Abedin asked him to come to Dhaka and enrol into the art school he had set up. In 1949, Qayyum moved into his sister's home in Siddeswari and then went to the art school, which at that time consisted of two rooms at the National Medical School in Victoria Park. Later, with the help of the then Prime Minister of East Bengal, the Institute of Fine Arts was established at its present location.

|

Drawing, Pen and ink, 1999. |

Upon entering the class Qayyum was a little taken aback to find that he would have to take an entrance exam. “Murtaja Baseer, Rashid Chowdhury and a few others were also taking the exam,” says Qayyum, smiling at the memory, “We had to sit on a stool with a board in front holding the canvas, it was called a donkey and we were asked to draw this kolshi placed in the middle of the room. I was nervous and was still sketching even when the time was over. Shafiuddin Ahmed, my teacher, said I had done enough. Zainul Abedin asked us to come into class next day with Chinese ink, brush, paper etc. I asked him what Chinese ink was and he said to Murtaja Baseer: “He doesn't seem to know anything, so please take him and get what he needs.” Baseer later became one of my closest friends.

It was a five-year certificate course. “When we got in we did not think about the future, we just jumped in blindly.”

The first thing Qayyum, still a teenager, had to worry about was how he would pay for his courses and materials as his family could not afford to. It was financial necessity that brought Qayyum into the field of graphic art and he started by doing covers and illustrations for textbooks and storybooks. After the Language Movement in 1952 the publications industry began to develop and Qayyum found more work. “I did about two to three books, each book required five layouts and I got 60 to 100 takas for each book.” Later of course this turned into another profession that paralleled his passion for fine arts.

|

| From left, Murtaja Baseer, Hasan Hafizur Rahman and Qayyum Chowdhury, 1963. |

The school followed the Calcutta Art School curriculum. The only art the students were exposed to were those of their teachers -- Zainul Abedin, Shafiuddin Ahmed, Anwarul Huq and Qaumrul Hasan. “We did not get much chance to see other artists' works. We did however have a library from where we could borrow books on art. We became inspired by artists like Picasso and Van Gogh who was my favourite. We were also enamoured by their bohemian lifestyles which we often tried to copy,” laughs Qayyum. But the students were exposed to other creative arts and had the opportunity to mingle with many poets, singers, writers and other artistes, thereby enriching their intellect. One of Qayyum's closest friends was writer Syed Shamsul Haq and the two would spend hours on end talking about art and literature. The friendship has endured all these decades. "Syed Shamsul Haq is the only witness of my work and its development," says Qayyum.

Dhaka, in the 50s, was still far from being urban and there was little patronising of the arts. After finishing his five-year course, Qayyum was eager to start developing a style of his own. Around 1954 or '56 Qayyum for the first time participated in a group exhibition and two of his paintings had been bought. At the time mainly foreign diplomats and officials would buy local paintings. "Geoffrey Hadle, the director of the British Council used to buy a lot of our paintings and became our friend. Later when he was transferred to Calcutta he invited us to visit him,” recalls Qayyum. During that visit, says the artist, Hadle took the group to watch 'Lust for Life', a film on Van Gogh that was showing in the Metro cinema hall. “So we had people like these to push us forward,” says Qayyum.

Accolades

Qayyum Chowdhury has won innumerable awards including: The Imperial Court Prize, Tehran Biennale in 1966; Gold medal for book design from the National Book Centre, Dhaka in 1975; The Shilpakala Academy Award in 1977; The Leipzig Book Fair Prize for Book Illustration;The Ekushey Padak in 1986; The 6th Bangabandhu Award in 1994; and the Sultan Padak in 1999. |

In 1960 Qayyum got married to Tahera Khanum, also an artist who was one of the first four girls to get admitted to the Art College in 1954. With a new sense of responsibility, Qayyum now had to think of earning more to support a family. He was at that time a teacher at the Art College, a job he left to join the newly established Design Centre to work under Quamrul Hasan. Within a year he decided to leave this job and he joined the then Pakistan Observer where he was Chief Artist. He also started working for the Observer group’s other publications namely Chitrali, a cine magazine and Purbadesh, a news magazine. At that time Qayyum would visit Zainul Abedin on his free days. Zainul Abedin's house was very close by and had become a place for regular adda. “One day I found Zainul Abedin sir alone and in a contemplative mood. He said he had seen an illustration of a boat in the Observer and asked who had done it. When I said it was me he demanded: 'Why can't you do this in paintings? Why not do them as compositions?'

“I went home and felt feverish. I called my wife and asked for my easel and canvas. And I just started to paint. From then on I would paint-- water colour and oil, before going to the office and after coming back. One day Abedin sir remarked: 'Whenever I look at your house at night, no matter what time, I always see light in your room. Why?' I answered that it was because I painted. He said, ‘One day you will get the result of this.’”

And Qayyum did get the result of his dedication. “One Sunday, when I had just returned around midnight from my in-law's place, Abedin sir's younger brother came and said, 'Miah Bhai is calling you'. I found him sitting on his usual rock, his vest on his shoulder. He looked into my eyes and gave me a tight slap and then fiercely hugged me. He then said he had received a telegram from Lahore where some of us had entered a competition and I had won first prize. It was a national award and I was quite shocked but I remembered those words he had said about getting the result.”

|

| Clockwise from Top-Left: At the artist's Naya Paltan studio, 1962. At his studio in Naya Paltan (2010). Qayyum Chowdhury in 1960. |

|

| Kansat Three, Pen and ink, 2007. |

About his mentor Qayyum says that Zainul Abedin never imposed his ideas on anyone but he always insisted that traditional art be kept alive. He had a huge attraction for art based on craft. Says Qayyum: “We don't have a painting heritage. So it is actually folk art that is our heritage.” In fact, his forthcoming exhibition in July is his interpretations of nakshikantha where folk motifs are used generously but in the particular style of the artist.

His most productive period says Qayyum was the 90s. It was after he had moved into his own studio in Naya Paltan that the speed of his work increased because of the space which allowed him to do larger-sized paintings.

Qayyum is very positive about the new generation of painters and believes that they are very conscious and sensitive about the socio-political developments in their country which gets reflected in their works. "Students and artists are always at the forefront and very vocal during national crises. Artists now also have immense scope to go out and see the works of artists in other countries. The Asian Art Biennale (in Dhaka) allows them to get such exposure. So it is a good sign that artists are availing these opportunities."

Artists actively participate in festivals like Pahela Boishakh and other secular occasions such as Ekushey February and Victory Day adds Qayyum, popularising them among the people.

|

|

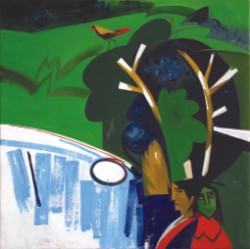

| Bangladesh 2001, Oil on canvas, 2002. |

7th March'71, Oil on masonite board, 1972. |

At 78, Qayyum is as active as ever. His daily routine includes waking up at 6:30 am for his 45 minute walk in Ramna Park followed by a heavy breakfast and then leaving his Azimpur flat to go to Naya Paltan where he has his own studio where he works till 3pm and steps into his own little world that is surrounded by music, literature and art.

|

| With newly-wed bride Tahera Khanam. |

His methods are meticulous as reflected in his work. “When I go out I always have my notebook with me. I do sketches and some of them serve as layouts for paintings. So I decide what colours to choose, etc. and then put them on the canvas. I have always used this method.”

Qayyum says that he takes up to 12 days to do a painting but takes two to three months to finish it. He usually works on several paintings at the same time.

Graphic design which has always been another facet of his career continues to preoccupy him. He has done a huge variety of work in this field -- book covers, layouts, posters, logos, record sleeves, even designs for saris. His earliest works include cinema posters for Zahir Raihan's film Behula and Chhatra Union's first poster that said “Esho Desh Gori” (Let's build our nation). Even now he is constantly called upon to design book covers, logos and illustrations by authors, newspapers, etc. Being able to create something new artistically is something that gives Qayyum a rush no matter what the format. But it has always been painting that has been his true love. "The most ancient history of painting is the history of civilisation. I can't think of a more exciting medium," says Qayyum.

|

|

|

| At the Azimpur flat of Aminul Islam in 1959, (from left) Mohammad Kibria, Aminul Islam, Rashid Chowdhury and Qayyum Chowdhury. |

Raining outside, Gouch, 1999. |

Pawnbroker, Oil on canvas, 1956. |

opyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |