|

Interview

Traditions that Transcend Differences

Professor Shamsuzzaman Khan |

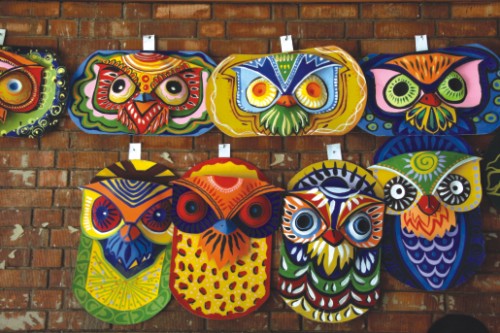

Every year on April 14, thousands of people in white-red saris and colourful panjabis brave the heat to join the parades, melas or family-and-friends gatherings around panta-ilish and a variety of bharta. Their faces painted, terracotta crafts and bright masks in hand, they celebrate the advent of the Bengali New Year. But has the day always been celebrated in this manner and what social relevance do these rituals have in our lives today?

Professor Shamsuzzaman Khan, Director-General of Bangla Academy, has spent most of his life studying Bengali culture and folklore. He has served as Director-General of the National Museum and Shilpakala Academy; taught at National University, Jagannath College and Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh and edited and continues to edit journals and magazines.

On the occasion of Pahela Boishakh, Professor Khan talks to Kajalie Shehreen Islam of The Star about the traditions surrounding the festivities, how they came about and their social significance for Bengalis.

How did the Bengali new year, that is, the Bengali calendar, come about?

The history of the Bengali new year and calendar is somewhat unclear and it is difficult to say exactly when it came about, but some assumptions can be made based on circumstantial evidence. The fact that it is called Bangla 'san' or 'saal', which are Arabic and Parsee words respectively, suggests that it was introduced by a Muslim king or sultan. Some historians suggest Moghul emperor Akbar, as he had reformed the Indian calendar -- with the help of his royal astronomer Fatehullah Shirajee -- in line with the Iranian nawroj or new day. Others suggest it was the seventh century king Sasanka.

I personally believe it was Nawab Murshid Quli Khan who was a subedar or Moghul governor and later a Nawab, who celebrated Bengali traditions such as the Punyaha, a day for ceremonial land tax collection. I believe he used Akbar's new year framework, revenue reforms and fiscal policy and started the Bangla calendar.

Why is Nababarsho celebrated on different days in Bangladesh and West Bengal?

An expert committee headed by Professor SP Pandya, after much scientific deliberation, set the date and their report was published in the Indian Journal of History of Science in 2004, where it was clearly stated that 'The year shall start with the month of Vaishakha when the sun enters nirayana Mesa rasi, which will be 14th April of the Gregorian Calendar.' The Indian government accepted this in 2002 but has not been able to convince West Bengal to adopt it.

How do Pahela Boishakh celebrations today compare to those you remember from your childhood?

The main element back then was the halkhata or the ceremonial opening of a fresh ledger by businesses. In our agriculture-based society, people were short of cash and would often buy on credit. On the first day of the New Year, shop owners would decorate their shops with paper flowers and dhoop (incense) and lay out sweets for the customers who would repay their debts in full or at least in part. It was a matter of social prestige to do so.

In this context, I would like to quote Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. I remember Bangabandhu, after forming the Planning Commission following the country's independence, saying that the members who were scholars trained in the west understood little about the lives of the rural people of Bangladesh, about the local context, geography, economy. 'In our agriculture-based society, people do not have cash all year. Even our fathers and uncles would buy a sari for their wives and hilsa fish on the new year,' said Bangabandhu.

Other Nababarsho traditions included the lathi khela and of course the mela or fair which would begin a day early on Chaitra Shankranti, the last day of the Bengali year, and continue for two to three and up to seven days. The mela was a source of entertainment as well as a place to shop and stock up on necessities, mainly kitchen utensils such as da, boti, kurol, wooden crafts, children's toys, etc., which were all available at these fairs.

Then there were the gorur larai (bullfight), morog larai (cock fight), putul naach (puppet show), jatra, etc., some of which still take place in certain parts of the country, though not as much. For example, some people in far-flung haor areas of the country still invest in expensive bulls and raise them to be able to win the bullfight at the new year.

From where did we derive and what is the significance of traditions such as eating panta-ilish on Nababarsho?

Panta-ilish is, I think, an unfortunate joke towards the poor.

However, there was a tradition called 'Amani', according to which the woman of the house would, the night before, soak rice and the twig of a mango tree in a pot of water and on the morning of the new year, sprinkle it on everyone in the family. This was based on a magical belief that the water would wash away the mistakes and negative aspects of the past year and bring peace to the family. This tradition is also empowering for women as they have the responsibility of this mangolikor wishing-well ritual.

Some aspects are also taken from early Nababarsho festivals, namely, Nabanno utshab, which is a thanksgiving ritual in which payesh is laid out by the river or for birds to have and which is also believed to bring peace.

How do you see the way in which Pahela Boishakh is celebrated today?

I see it very positively. I think the celebrations are a sign of national cohesion regardless of religion, caste and creed. It is a national festival. It has taken positive aspects from Amani, Nabanno, etc., and is a wonderful mixture of several traditions. The parade brought out by the Institute of Fine Arts, for example, is an extension of the michhil or processions that used to be brought out in the villages. The parade with masks of owls, snakes and more have a multidimensional meaning and metaphor. They are a symbol of protest. They first began in 1989 when, under the autocratic rule of General Ershad, people could not protest openly and this was a symbolic way of doing so. Even today, they are symbols of protest against governments and political parties which are communal, oppressive, etc. Bengali culture is a mixed, secular culture and the Pahela Boishakh celebrations are a reflection of this, invigorating our culture even more.

Do you think Bengali culture is in the face of any threats?

There are the threats of globalisation, satellite culture, etc., but I believe our culture is so powerful that it will survive the onslaught of these. It has had to be accepted even by these elements, which use, for example, Baul songs, in perhaps a different form and of course for their own profit, but the important thing is that they are not being able to deny its presence and power. Bengali culture has the strength to adjust to new situations, and it is based on human values. The phrase that parents are always telling their children, 'Manush hou', cannot be translated into English; 'be human' does not carry the same connotations that it does in Bengali. But the original phrase is proof of how humans and human values are put above everything else and that is the essence of our culture.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010

|