|

Tribute

Rebelling from Within

With religious parochialism raising its head more alarmingly than before, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain's writings and thoughts are becoming more relevant in the contemporary world

RIFAT MUNIM

When the west was preparing for the World War I that would epitomise once again the destructiveness of male militarism; and when most of the Asian and African countries, having dealt with the impact of a European-styled renaissance, were facing the dilemma of whether or not to continue the colonial legacy, a Bengali woman in the then undivided India devoted herself to the construction of an ideal world where, she writes addressing explicitly the women, the men are forced to remain inside the house to look after the household chores including cooking and the women are responsible for ruling the country known as the Ladyland, advancing it to prosperity by means of scientific research and intellect.

The unparalleled woman in focus is Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and the feminist utopian short story, referred above, is 'Sultana's Dreams', the first of its kind in the whole world, which was followed a decade later by the much better known feminist utopian novel 'Herland' by the American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Rokeya's story was written in English and published in a Madras-based English periodical called 'The Indian Ladies' Magazine'. It is not known if Gilman read Rokeya's story, but considering the contents of both stories, which lie in demonstrating women's equal rights, one would be apt to say that Gilman's story owes much to Rokeya's. The unparalleled woman in focus is Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and the feminist utopian short story, referred above, is 'Sultana's Dreams', the first of its kind in the whole world, which was followed a decade later by the much better known feminist utopian novel 'Herland' by the American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Rokeya's story was written in English and published in a Madras-based English periodical called 'The Indian Ladies' Magazine'. It is not known if Gilman read Rokeya's story, but considering the contents of both stories, which lie in demonstrating women's equal rights, one would be apt to say that Gilman's story owes much to Rokeya's.

Although Rokeya was preceded by the likes of Mary Wollstonecraft, who wrote 'A Vindication of the Rights of Woman' in 1792; Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who wrote 'The Woman's Bible' in 1895, among others, it would be most appropriate to say that she was the first female writer in whom converged all the different literary genres including fiction and non-fiction that feminist writers manipulated in different periods of history to assert their rights. Yet, it was not until recently that Rokeya's works are being read with utmost seriousness in abroad, especially in many of the American and European universities.

“She is the first feminist writer of the Indian Subcontinent. When women in development (WID), a theory advocated by the United Nations, had failed, the UN suggested the gender and development (GAD) theory. When GAD failed too, it came up with other development theories most of which were envisioned by Rokeya almost a hundred years ago,” says Selina Hossain, the critically acclaimed writer.

|

Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain promoted the idea of self-reliance as the basis of women's freedom. Photo: zahedul i khan |

Syed Manzoorul Islam, litterateur and professor of English at Dhaka University, extends the points made by Hossain. He says, “she is one of the earliest feminist writers of the twentieth century, one who came up with a holistic approach to feminism both in its theoretical and pragmatic dimensions. May be that is why many of the American universities like the Illinois State University has included Rokeya's texts as part of its feminist studies.”

Rokeya, who was born on December 9, 1880 at Pairaband in Rangpur into a conservative Zamindar Muslim family, was denied access to formal education altogether. But it was from her generous elder brother, who believed in women's education, that she learned Bengali and English. In 1898, she was married to Syed Sakhawat Hossain, an Urdu-speaker from Bhagalpur in Bihar. A deputy magistrate by profession, Sakhawat Hossain was liberal and progressive, and encouraged his wife to read literary works from home and abroad. Within a few years of her marriage, she showed her flair for literature by publishing some of her essays and the celebrated 'Sultana's Dreams'. Unfortunately, her husband died in 1909. Meanwhile, she had given birth to two daughters, but they died in infancy. After her husband's death, a dispute with her stepdaughter's husband arose and she decided to leave Bhagalpur and settle in Kolkata. Despite all her personal losses, she began to continue her literary and social activities in Kolkata more unflaggingly than ever before.

She cut a figure among the readers for her essays, most of which were compiled in Matichur. Among these, Strijatir Abanati (Subjugation of Women), Ardhangi (The Better Half), Griha (The House), and Borka (The Veil) are her strongest polemics against the repressive constraints imposed by men on women. Abarodbbasini (The Secluded Ones) published in 1929, which is a collection of journalistic vignettes of purdah observance, also struck the consciousness of many readers. Much like all the modern feminist theorists such as Virginia Woolf and Simone de Beauvoir, she strongly argued in the Strijatir Abanati that the centuries-old perception of a woman's identity was not natural to her being, rather constructed by men with a view to shutting women inside home and forcing them to remain in purdah, a custom which does not allow women to appear before men. On one hand, she negates the patriarchal way of associating a woman's identity with jealousy, incompetence, weakness, irrationality and lack of intellect; and vehemently reprimanded the women for unthinkingly acquiescing with the men on the other hand. She clearly pointed out that illiteracy and unemployment were the main reasons behind women's subjugation. But what makes her essays stand out quite distinctly is the logical manner in which all arguments are presented. When this logical strain is combined with sarcasm, the outcome was so influential that it immediately attracted a huge readership both supporting and opposing her views.

“She rightly underscored self-reliance as the basis of women's freedom, which cannot be achieved without education and employment,” says Islam.

|

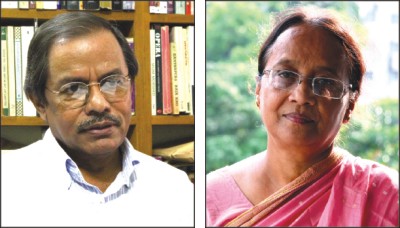

L-R: Syed Manzoorul Islam and Selina Hossain. Photo: Zahedul I Khan

|

A critical reading, however, would reveal that Rokeya's uncompromising attitude towards the excesses of purdah observance waned a little in 'The Better Half'. The extremely conservative context which naturally triggered huge reaction among the Muslim readers, especially against her stance on purdah observance, made her realise that she would have to rebel while also being a part of it, not by completely going against the grain. So she justified purdah on religious grounds. Nevertheless, she stuck to the principle of women's equality in all spheres of social as well as familial life and continued to stress more vociferously the necessity of education and employment. Above all, she always reiterated the importance of women's mental powers by which she meant a resurrection of self-confidence in women about their worth and equality.

“Instead of defying religion wholly, Rokeya coordinated it with work and tried to logically show that education and employment, which are the fundamental pillars of women's freedom, do not contradict religion,” says Selina Hossain.

Professor Islam says that Rokeya was very different from today's feminists who are up in arms about their rights. She was rather persuasive, who preferred to speak from a traditional point of view, blending the power of wit with logic – all of which helped to reach a wider audience and generate a social movement.

“Many of today's feminists are marked by NGO culture which is more oriented to bringing funds based on false reports on issues such as arsenic and AIDS. In sharp contrast, Rokeya didn't hurt people's feeling insensitively because she believed in participatory democracy. So she took into account people's, especially women's, opinion before coming to a resolution,” he says.

Referring to Rabindranath Tagore, he says that there are many points of similarity between Tagore and Rokeya.

“Like Tagore, Rokeya believed in religion, but not in its institutionalisation which is often controlled by the religious priests or mullahs who do not bother much about what the scriptures really say. So even though she was a believer, she believed that religious structures were made by men to serve their own interest,” he says.

While the topicality of her essays made them contextualised, delimiting her freedom of thoughts and making her at times compromise with the prevalent ideologies, fiction offered her ample opportunities to explore her thoughts to the fullest extent. That is why one finds her reinless in her fiction, especially in 'Sultana's Dreams', where she can boldly negate as well as reverse all the existing norms and customs, including those reinforced by religion. Toward the end of the story, when Sultana asks Sara about the religion of the Ladyland, the latter replies:

“Our religion is based on Love and Truth. It is our religious duty to love one another and to be absolutely truthful. If any person lies, she or he is….”

“Punished with death?”

“No, not with death. We do not take pleasure in killing a creature of God, especially a human being. The liar is asked to leave this land for good and never to come to it again.”

The same is also true of 'Padmaraag', another utopian novel by Rokeya where Siddiqua, one of her boldest female characters, much like Ibsen's Nora, slams the door on her husband and leaves him forever only to show that a woman's life may mean a lot more than being confined to the four walls of marriage.

About the potentiality of 'Sultana's Dreams', Professor Islam says, “It always startles me to think how the women of the Ladyland defeat their male counterparts. They do it not with their muscle, but with their brain. Combining imagination with science, they show, the aesthetic power of science can truly put an end to war and bring peace to any country.”

Apart from her most familiar write-ups, Selina Hossain refers to many of her lesser-known articles, which were anthologised in her oeuvre published by the Bangla Academy.

“When I read her articles such as Niriha Bangalee, Chashar Dukhkhu, and Andy Shilpa, I find somebody who was highly concerned about how to equip our farmers with modern as well as scientific methods and thus solve many agricultural problems. That is why I am really hurt when people now call her merely a feminist. She actually raised her voice against injustice, be it based on gender or class,” she says.

Besides establishing women's education in the subcontinent, she also founded Anjuman-e-Khawatin-e-Islam in 1916, an organisation that provided employment for women.

“I think she is the most undervalued feminist of the twentieth century. So she must be brought to the limelight not only in South Asia, but also in the whole world,” says Professor Islam.

“I think all her writings should be translated, otherwise readers outside the Bengali-speaking communities cannot access her thoughts,” says Selina Hossain.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2010 |

| |