| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 47 | December 16, 2011 | |

|

|

Cover Story 5: Media

Fourth Estate Flexing its Muscle One of the principles based on which ordinary Bangladeshis fought a bloody and ruthless war against the oppressive Pakistani ruling class was their right to speak without fear or favour. But as it had happened to other such ideals in the nascent nation's chequered history, the people's right to speak freely was strangled within a few years after the country's independence. All but four newspapers were banned; the state-media, including the radio and television, remained tightly in the grip of the government. After the brutal and barbaric murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and some members of his family, the military dictatorship of different hues and colours that ruled the country throughout the late 70's and the entire 80's tried to control the media by dictating to the newsrooms what news would go in the following day's paper and what treatment should be given to them; and when the water turned choppier, they would send men in uniform to the newspaper offices, ordering the editors to block a certain news or to highlight their preferred ones. It remained a dark era in the history of journalism in Bangladesh. Newspersons were abducted and tortured in the dungeons run by Gen Zia and Lt Gen HM Ershad's secret service; newspapers were often banned and their editors were threatened. It is a small wonder, then, that the number of newspapers skyrocketed within a few months after the fall of Ershad's despotic and corrupt regime in a mass upsurge. Many independent newspapers were born and after the country's airwave was set free, a good number of private television channels quickly replaced the age-old government-controlled Bangladesh Television. The government later allowed private entrepreneurs to establish radio stations, and they have wooed the younger generation of radio listeners, who would not have otherwise listened to the state-run Bangladesh Betar. Media is not, however, as free as it should be in a democratic state. Even after the restoration of democracy in 1990, journalists were killed, their houses bombed or they are threatened with dire consequences by ruling party-men or local thugs. As it happened in the era of military dictatorship, the newspersons, in democratic Bangladesh, are fighting a day to day battle to uphold the people's right to speak. Despite this, the media in the country has flourished to such an extent that its power in opinion building cannot be denied. The Fourth-estate is flexing its muscle, and in the days to come, its strength and ability to fight injustice and corruption will decide the future of a democratic and free Bangladesh. TV

From One to Many

Gone are the days when Bangladeshis could only enjoy six to eight hours of television. Gone are the days when their programmes of choice would be limited within the pages of a book called BTV guide. Today with 23 local private channels and scores of international satellite channels, airing programmes 24/7, the options opened to Bangladeshi viewers are unlimited. Bangladesh Television (BTV) that started in 1964 had been suffering from stagnancy in the late 80s due to political influence and lack of new talent. Towards the beginning of the 1990s, BTV began airing programmes bought from outside production houses, to bring a change to its staleness. The initiative induced new tastes among viewers, who had already turned to foreign channels and Indian film video cassettes for entertainment.

That is when the private satellite channels came to the rescue. The small screen experienced a great leap towards the end of the 90s when these channels entered the Bangladeshi air. The bright, fresh and less partisan looks of the private channels immediately gained popularity among viewers. New programmes free BTV stereotypes began to evolve— game shows, reality shows, talk shows, investigative and on the spot reporting, live music shows and many more. Even new trends in Bengali TV drama — script-less drama, telefilms, drama using colloquial language, to mention a few have begun to appear. The increasing number of local private channels has made it possible for many artistes to explore their hidden talents and reach the public eye within short a space of time. Competition to produce programmes has made it possible for artistes to consider their profession seriously rather than as hobby, like it was in the BTV days. Similar to mobile phones, private television channels are ensuring increasing access of information, often enforcing accountability of government bodies. However since the terrestrial license is still being withheld by government, these channels cannot reach the million others in Bangladesh who are beyond the reach of cable operator's network. Magsaysay Awardees

Jewels of Asia

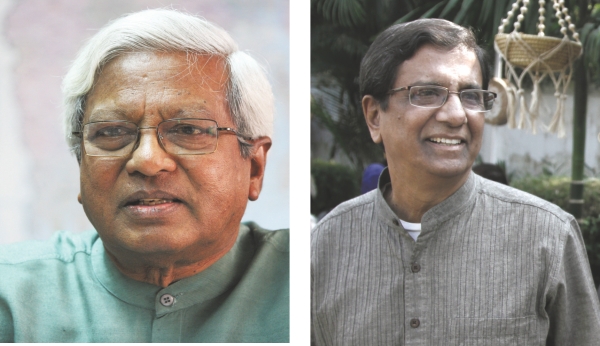

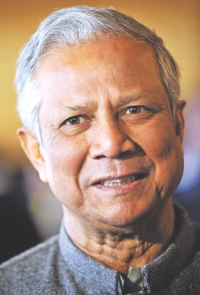

In its forty years of independence, nine individuals have made the country proud by earning the Ramon Magsaysay Award, often considered as Asia's Nobel Prize. Tahrunnesa Abdullah is the first Bangladeshi to receive the Ramon Magsaysay Award in 1978 in the Community Leadership category for "leading rural Bangladeshi Muslim women from the constraints of purdah toward more equal citizenship and fuller family responsibility". Her work at the Women's Programme, of Bangladesh's Integrated Rural Development Program (IRDP), challenged the misconception about rural woman and gave new dimension in development programmes. Sir Fazle Hasan Abed received the 1980 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership. As the founder of BRAC, his 'organisational skills in demonstrating that Bangladeshi solutions are valid for needs of the rural poor', brought him this special recognition. Nobel Laureate Mohammad Yunus received the 1984 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Community Leadership in recognition of his contribution and innovation of micro-credit. Founder of Ganoshastho Kendro, People's Health Clinic, a charitable trust, Dr Zafrullah Chowdhury received the 1985 Ramon Magsaysay Award in the Community Leadership category for 'engineering Bangladesh's new drug policy, eliminating unnecessary pharmaceuticals, and making comprehensive medical care more available to ordinary citizens'.

In 1987, Fr Richard William Timm, received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for International Understanding for his 35 years of 'sustained commitment of mind and heart to helping Bangladeshis build their national life'. Fr Timm, after his arrival in Bangladesh in 1952, established the department of science at St Gregory's College (now Notre Dam college). As National Director of Caritas Bangladesh, he directed and monitored projects in irrigation, drainage, health and jute handicrafts, cutting through bureaucratic obstacles and moving practical assistance to the villagers. Unlike the other Bangladeshi Ramon Magsaysay awardees, Mohammad Yeasin, neither holds an academic degree or expertise. With a humble beginning as a tea-shop proprietor he became the founder of Deedar Comprehensive Village Development Cooperative Society 'moving rural Bangladeshis to self- reliance and economic security through an efficiently and honestly managed village cooperative'. He received the award in 1988 for Community Leadership.

Founder of Banchte Shekha or Learning to Survive, Angela Gomes received the 1999 Ramon Magsaysay Award in the Community Leadership category, in recognition of her contribution in 'helping rural Bangladeshi women assert their rights to better livelihoods and to gender equality, under the law and in everyday life'. With the slogan “Alokito manush Chai” (In search of enlightened individuals) Professor Abdullah Abu Sayeed launched the Bishwo Shahitto Kendro, or World Literature Center in 1978 to 'enlighten human minds'. He continued his endeavour by bringing forward the country’s only mobile library in 1998. Through the 2004 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts, Professor Sayeed has been recognised for 'cultivating in the youth of Bangladesh a love for books and their humanising values through exposure to the great works of Bengal and the world'. Editor of the leading Bangla daily “Prothom Alo”, Matiur Rahman received the 2005 Ramon Magsaysay Award for Journalism, Literature, and Creative Communication Arts. Through this award, his contribution in 'wielding the power of the press to crusade against acid throwing and to stir Bangladeshis to help its many victims', has been recognised. One of the chief founders of Centre for Disability in Development, A H M Noman Khan received the 2010 Ramon Magsaysay Award, for 'leadership in mainstreaming persons with disabilities in the development process of Bangladesh, and in working vigorously with all sectors to build a society that is truly inclusive and barrier-free'. Photograpgy In Focus

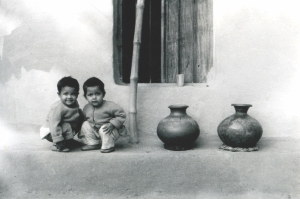

Bangladesh's passion for photography is evident in the quantity of talented photographers in this country and in the quality of photographs produced. Since independence, numerous photographers have made their mark in national, regional and international arenas, winning awards, accolades and respect of people all around the world. Begart Institute of Photography, established by Manzoor Alam Beg, was the first photographic educational institute in independent Bangladesh and has produced some of the country's finest photographers. Bangladesh Photographic Society (BPS), founded in 1976, was the first photography gallery of Bangladesh with its own darkrooms and class rooms. Under the leadership of the Beg, BPS received acknowledgement and acceptance as the country member of the International Federation of Photographic Art (FIAP). Meanwhile, photographers like Rashid Talukdar, Aftab Uddin Ahmed pioneered the field of photojournalism and captured some of the most memorable moments in the history, politics and culture of Bangladesh. However, despite the combined efforts of press photographers, photojournalism as a field has not always received proper acknowledgement. As of now, the concept of photo editors does not exist in our country. Drik was the first picture library in Bangladesh; two decades after its inception, it has become a major photographic organisation in the region. Its educational wing, Pathshala, South Asia's premier institute of photography, is a world-class institution that hosts students and photographers from all over the world. Chobi Mela was first launched by Drik as South Asia's largest festival of photography in 2000. Bangladesh has hosted around 400 international photography events under the placard of Chobi Mela. Bangladeshi photographers have won innumerable awards. Among the many recipients of the prestigious FIAP award was Manzoor Alam Beg; of Commonwealth, among others, Anwar Hossain; of Mother Jones, Abir Abdullah, Shehzad Noorani and Shahidul Alam. World Press Awards were given to Shafiqul Alam Kiron, GMB Akash, Shoeb Faruquee and Andrew Biraj. Many of our brilliant photographers, including Munem Wasif, were selected as participants for the Joop Swart Masterclass. Rashid Talukdar received the 2010 National Geographic All Roads Pioneer Photographer award for his photo-essay "The 1971 Liberation War." Shehab Uddin and Saiful Huq Omi also received awards from the National Geographic All Roads. Shahidul Alam has the distinction of being the first person of colour to chair the international jury in World Press Photo history.. Film

Taking a Different Path

The alternative cinema movement in Bangladesh, in the form of short and independent films, is perhaps one of the most significant prizes of the Liberation War. Started by a group of young film-makers, in the 1980s, the movement campaigned for a creative and aesthetically rich cinema. The movement led to the creation of Bangladesh Short Film Forum as well as many notable film societies, which not only encourage production of good films but also educate public about best practices around the world. Some of Bangladesh's most notable filmmakers and film activist including the late Tareq Masud, Tanvir Mokammel, Manzarehaseen Murad are the pioneers of this movement. It led to the creation of internationally acclaimed films like Matir Moina and Chaka. The Short Film Forum organises the biennial and non-competitive International Short and Independent Film Festival. First held in 1988, it was the first festival in the Indian Sub-continent which was entirely dedicated to short film. The film societies, on the other hand, keep the movement alive by organising documentary and feature-films festivals. Rainbow Film Society, one of the oldest in Bangladesh, initiated the International Dhaka Film Festival in 1992, opening the window of world cinema to the cinema-lovers of the country. While the full-length feature film industry is experiencing a decline because of out-dated technology and production and sub-standard storyline and direction, some directors do venture to take a different path. Their yearning for better cinema bring Bangladesh honour in the form of international awards — the most recent being bagged by Nasiruddin Yusuf's ‘Guerilla’, winning the prestigious Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema (NETPAC) award at the Kolkata Film Festival. Sport

Sports Through the Years Quazi Zulquarnain Islam The superlative exploits of one Brojen Das might have preceded the years of independence, but it was the fire that burnt heavily in his belly that inspired a clutch of famous sportsmen to hoist Bangladesh to new heights on the international arena. Das swam the English Channel, not once, not twice but four times. His early years in Munshiganj beside the mighty Padma might have prepared him for such feats but what is clear is that he became a marker against which every future Bangladeshi sportsperson would be judged.

Cricket is the new flavour and might be dominant now, but in its wilderness years in the late 70s and early 80s, it was football that was the sport of choice as Bangladesh rubbed shoulders, and dispatched with the likes of Thailand and Indonesia. Kazi Salahuddin strode the professional circuits of Hong Kong like a titan and Bangladesh looked set for a bright future in the beautiful game. While that dream has quickly dissipated amidst the empty dustbowls strewn across the country, another has emerged. Ironically the game passed onto us by our colonial masters somehow seeped through to the masses and wielding a willow became almost a rite of passage for every Bangladeshi child. And ever since Gazi Ashraf Hossain Lipu walked us out to our first ODI in a tiny sea-side town in Sri Lanka in the late 80s, the only way has been up. Currently, the likes of Shakib al Hasan and Tamim Iqbal are world beaters in their own right but they follow the examples set by people like the obdurate Aminul Islam Bulbul whose century in our debut Test against India encompasses all those qualities that make us proud to be Bangladeshi. But even as cricket reigns supreme, there have been other highlights. Asif Hossain Khan shot us into relative glory achieving a Commonwealth gold, but it is a measure of how little we can improve, that the man he beat won an Olympic gold in 2008 while Asif barely qualified. This has been a recurring pattern even as the noughties roll in, but it has brought with it new heroes. One-time caddy Siddikur Rahman is writing his own rags-to-riches story in the game for elitists and our women too are showing the way; Salma Khatun and Khadiza tuz Kubra are two of the many showing the way towards a new future. The writer is a senior subeditor of The Daily Star.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||