| Home - Back Issues - The Team - Contact Us |

|

| Volume 10 |Issue 47 | December 16, 2011 | |

|

|

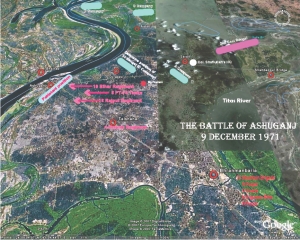

Remembrance The Road to Dhaka SHAHZAMAN MAJUMDAR, Bir Protik reminiscences about the battle of Ashuganj and the Muktibahini's march towards Dhaka The Battle of Ashuganj On December 9, Delta (D) Company under the command of Lt. Nasir took defensive positions in foxholes at Durgapur. Durgapur is a village about two miles from Ashuganj and approximately one mile from the banks of the Meghna River (see Map). About 500 yards to the left of Delta Company were 8 Indian PT-76 tanks, the 10 Bihar Regiment, and the 18 Rajput Rifles Regiment. The 10 Bihar had taken part in the attack at Akhaura on November 30. At 11:00 a.m., we came to know through the Indians that the Pakistani Army had withdrawn from Ashuganj to Bhairab Bazar. This became all the move evident as the Pakistanis had destroyed Bhairab Bridge at around 9:30 a.m., the same day. In addition, the Pakistanis were occasionally shelling Ashuganj, even firing heavy machine guns from across the river at Ashuganj. Meanwhile, 18 Rajput was ordered to advance and capture Ashuganj, the eight tanks and 10 Bihar following them. When these developments were taking place, Maj. Matin and I were coming toward our forward elements at Durgapur. Our small group included Maj. Matin's runner Mujib, a wireless operator, and another person, a local guide. Maj. Matin had met Col Shafiullah at around 9 a.m., and after the meeting, he wanted to inspect the forward areas of the battalion. Our small group was heading cross-country following the Sarail-Ashuganj road. We were about 100 metres to the left of the road when we found elements of the 10 Bihar in front of us. They seemed to be heading toward Ashuganj. I saw the Indian tanks in the distance, heading toward Ashuganj. We decided to head right, toward Durgapur. Meanwhile, the 18 Rajput, assuming that Ashuganj was abandoned and undefended, started marching quite casually. Many of the 18 Rajput and 10 Bihar soldiers had their weapons slung over their shoulders, indicating that the troops were quite relaxed. In the distance, to our right flank, we saw some more troops heading toward Ashuganj. From the distance they looked like our troops—the forward elements of the 11 Bengal but we could not be certain. Wanting to remain with the forward elements, we decided to follow the Indian troops. The Pakistanis, being driven from everywhere had congregated in Bhairab. They knew that they would not be able to defend Ashuganj. Bhairab, behind the mighty Meghna River, offered a superior defensive location. Despite this, the Pakistanis planned a death-bite; a last-ditch effort to inflict heavy losses on us. As a result, two battalions of Pakistani regulars were hiding behind the wall of the power station. They also had with them a few recoilless rifles (used against tanks). They waited patiently until 18 Rajput reached about 50 meters from their position. Suddenly, I heard three large booms, nearly simultaneously followed by plumes of black smoke as three Indian tanks were hit—point blank—by 106 mm anti-tank armour-piercing shells. At the same time, the entire battlefield erupted in all sorts of small arms fire.

At first, our small group became confused, failing to understand what was happening. There was a small mound nearby and our small group took position behind it. Bullets were flying overhead, even though we were about a kilometre and half from the Pakistanis. Maj. Matin and I took position on top of the mound; the flat terrain offering us a clear view of the battlefield. Maj. Matin had a binocular and it gave us a magnified view of the battle. When the 18 Rajput was advancing, the forward elements of the 11 Bengal, one company led by Lt. Nasir, also left their foxholes and started advancing toward Ashuganj. They were to the right of 10 Bihar and the tanks, about 500 meters behind the Indian contingent. When they saw the Pakistani attack, they immediately retreated near Durgapur and started taking defensive positions. The Pakistanis, on the other hand, encouraged by their initial success, came out from their hidden positions; shouting “Ya Ali,” “Ya Ali,” charged the retreating and disorganised Indians. There was complete chaos among the Indian troops. Some took position in the coverless terrain and started shooting at the charging Pakistanis, while some others started retreating in panic. Some of the elements of the 10 Bihar, after being chased by the Pakistanis, came near Lt. Nasir's position; some of them were fleeing to his rear. Soon the left flank of the charging Pakistanis came very close to Lt. Nasir's position and now it was time for the Pakistanis to be surprised. Lt. Nasir opened fire on the Pakistanis with one medium machine gun and everything else he had, taking the Pakistanis completely by surprise. The Pakistanis, obviously, were not expecting any resistance. They could see that the Indians were retreating, their tanks heroically trying to shelter the infantry from the Pakistanis. A group of Pakistani soldiers had reached too close to Nasir's right flank and a section of the defenders panicked. Learning that the panicked soldiers were about to abandon their position, Lt. Nasir quickly moved to his right flank and was relieved to see that the platoon commander, a fresh second Leintenant., was chasing the fickle-minded with the butt of his SMG and driving them back to the trenches. Relieved, Nasir went back to his position at the center of his company. Chaos now ruled the charging Pakistani column. Some were crawling and trying to shoot; some others, panicked, were running aimlessly, without any apparent purpose or direction; while a few tried to assist their injured comrades, it was total chaos. Lt. Nasir's Chinese machine gun was firing continuously and soon the barrel was glowing red from overheating, the machine gun continued to fire. After a while, the remaining Pakistanis started retreating to their initial position behind the walls of the power station. As soon as the Pakistanis retreated, the Pakistani artillery unleashed a vicious barrage on Lt. Nasir's position, forcing him to fall back about a mile and retake position there. We saw the major elements of the battle from our vantage point. As the battlefield was becoming deserted, and without knowing precisely the location of our forward elements, we decided to join Alfa Company, which was not far. The debacle in Ashuganj was taken very seriously by the Indian High Command. On the following day, the battalion commander of 18 Rajput Rifles was replaced. The Indian artillery batteries were moved within range of Ashuganj and Bhairab and started a massive barrage. Indian jets attacked Bhairab and we saw them drop Napalm bombs, which exploded with a tremendous boom and massive fire. We could see the conflagration engulfing wide areas and the plumes of black, red, and purple smoke from a long distance. On December 10 , the 10 Bihar and 18 Rajput joined Lt. Nasir's position at Durgapur. Lt. Nasir was forced to take position again at Durgapur by Maj. Matin. The entire battlefield was littered with corpses—some of them had already started to rot. The barbaric. Pakistanis had beheaded some of the dead or dying Indian soldiers and had carried the heads with them. It was a beastly sight. Meanwhile, most of the Pakistanis had fled from Ashuganj on the night of December 9. Therefore, when we advanced on Ashuganj on the 10th, we found only a few Pakistanis. No Pakistani prisoners were taken in Ashuganj on the 10th. Major Matin and I entered Ashuganj on the 11th. The corpses of Pakistani soldiers littered the entire battlefield. Some had died of bullet wounds, some fell victim to the air attacks, while other by artillery bombardment. Both sides of the road from Talshahar to Ashuganj were filled with thousands of crates of ammunition, piles of crates after crates, stacked on top of the other. I had never seen so much ammunition in my entire life. Everything was there—artillery shells, mortar bombs, small arms ammunition, anti-tank ammunition, various types of mines, rockets, and even anti-aircraft shells. Some of the boxes were intact while many others were open and the contents spilling on the road. By the night of December 11, all the elements of our battalion were in Ashuganj and took position facing Bhairab. The Pakistanis were intermittently shelling Ashuganj. We also found them firing heavy machine guns from across the Meghna River. Road to Dhaka

After the battle of Akahura and Ashuganj, the Indian strategy changed. Instead of attacking the Pakistani hardened defenses located mostly on the major towns, the Indians decided to surround and bypass them. The 11th East Bengal Regiment was given the responsibility to contain the Pakistanis at Bhairab. A massive search of Ashuganj was undertaken. We found only a large number of corpses but not any live Pakistanis. I saw a mass grave of Pakistani soldiers near the Power Station's officer's quarters, in a small park. The graves were neither properly constructed nor had the dead bodies been properly buried. It seemed very similar to the mass grave I had seen at Jagannath Hall—many of the heads and legs were sticking out of the graves. The crows and dogs had not yet arrived because of the battle. But vultures had already discovered the corpses and were having a feast. What an irony of fate—did any of these soldiers and officers participate in the massacre of Jagannath Hall I wondered. The Pakistanis again started shelling Ashuganj. Since Maj. Matin and I were the veterans of Akhaura—it did not bother us much but the rest of the battalion considered the shelling quite severe. Maj. Matin had setup the battalion headquarters in a vacant officer's quarter of the power station. These apartment type buildings were quite sturdy and could even withstand a direct hit by artillery shells. Compared to a position behind a wall, the current protection was like living inside an iron-fortress—while inside the building I did not even flinch when the Pakistanis shelled us. The Indians gave us an artillery observer and there were two medium artillery guns somewhere to our rear to give us artillery support. Our daily activities included taking a suitable position behind a wall near the riverbank and try to spot using the binocular any Pakistani movement on the Bhairab side of the river and direct artillery fire on the Pakistanis. The Pakistanis also from time to time shelled us. It was great fun particularly when we saw the shells directed by us hit the Pakistani targets. This is how we remained in Ashuganj until we heard of the Pakistani surrender on December 16 1971. It is impossible to express the feeling of how I felt at the news of the Pakistani Surrender. We became ecstatic; we were jubilant; we became like children firing our weapons in the air as if they were toys; we hugged and embraced each other; we were dancing in wild celebrations; our joys knew no bounds; our country was finally free and independent and we had finally defeated the brutal, savage, murderous, and bloodthirsty Pakistanis. We, however, could not immediately leave Ashuganj and remained there until the 22nd, when we left Ashuganj by boat for Narshingdi. A train was waiting for us at Narshingdi and we came to Dhaka the same afternoon. The Vikarunnessa Noon School was assigned for our troops and the adjacent Maghbazar Preparatory School was assigned for the officers. When we reached Dhaka, the initial euphoria and celebrations of finally becoming an independent nation had somewhat subsided. I saw many well fed people brandishing a variety of weapons with a red cloth tied to their forehead everywhere. They identified themselves as the crack-platoon, the freedom fighters of Dhaka. They had commandeered various types of vehicles and we found them speeding through Dhaka streets. We, the regular troops, exhausted from battle, the sleepless nights at the front, and mostly suffering from malnutrition, looked pale in comparison. Were there really so many people in the crack platoons? It seemed that whoever could find an abandoned weapon of the Pakistanis had now turned into a freedom fighter. I discovered some of my old acquaintances of Minto Road, none of whom I could find after 25th March were now moving around with the red cloth tied to their foreheads and carrying AK-47s! None of my immediate family was in Dhaka. Both my brothers-in-law and my brother were transferred to West Pakistan. My eldest brother and mother were in Dinajpur. I, however, could find some of my college friends including the one I had met on April 3, prior to leaving Dhaka. Though he did not carry any weapons, he was now full of bravado and proud of how 'we' had defeated the Pakistanis. The Indian army was everywhere and people cheered them whenever they passed. Even though the initial wild celebrations had died down, there was a general confidence among all. After all, after a long struggle finally the Bangalis now had a nation of their own. Now we could build a society based on fairness and rule of law enabling us to achieve the cherished dreams of peace, prosperity, and progress. Finally we would be able to proudly stake our rightful claim among the rank of independent nations. Time had come when all our problems would finally be resolved. This was exactly what everybody's expectation was. After defeat of the Pakistanis, the people developed enormous confidence in the capabilities of Bangalis. The traditional divide between Hindus and Muslims seemed resolved forever. It appeared that finally the deep scar of the 1946 Hindu-Muslim riots had been erased. The religious divide between Hindus and Muslims seemed banished permanently from the free land of the Bangalis. The euphoric jubilations made us forget the challenges of rebuilding. Most of the national assets were destroyed; all major bridges and majority of the culverts were destroyed making communication within the country extremely difficult. The economy had come to a standstill. Many agricultural lands lay fallow. The state machinery had completely collapsed. There was no administration in the country. In the absence of administration and law enforcement, the country ruled by itself—only through the goodwill and positive attitude of the people and maybe because most people were armed. It was a great challenge to build a nation from scratch—whoever came to power. The fate of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remained uncertain in the Pakistani prison. Would he be able to come alive and lead the country, the dream of which he had created among the Bangalis? There was no shortage of claimants of victory. Everybody who had crossed the border now had become freedom fighters. Those who had collected an abandoned weapon after the Pakistani surrender were now freedom fighters. Therefore, in the forest of millions of freedom fighters, those that had actually confronted the Pakistani Army in combat became an insignificant minority and were soon forgotten—no distinctions remained once victory had been achieved. On December 24, Maj. Matin and I were coming from somewhere in a jeep and had stopped at the intersection in front of what is new the Scouts Bhaban when another car stopped by the side of our vehicle. I was in a khaki uniform and was carrying my AK-47. A gentleman shouted at me through the rolled down window of a car, “Isn't it Shahi (my nick name, only used by family members).” I recognised him—he was Asaf Khan, a renowned businessman during the 70s and 80s and an acquaintance of my brother-in-law. He shouted through the car's rear window, “Do you know that your brother-in-law was transferred to Pakistan?” Without waiting for my answer, he continued, “Do you know about your mother and brother in Dinajpur? Do you know that they had been killed by the Pakistani Army?” Before I could respond, the traffic signal turned to green and both the vehicles started moving. I kept on sitting on the jeep, my brain unable to process all the data immediately. Maj. Matin was looking at me; I could discern his grieving eyes. I did not have any reaction. It seemed to me to be the most natural thing. I could cry for Rafiq but I could not cry for my mother or brother. 1) The death figures are from the Indian Defense Ministry figures published after the war. Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011 |

Before the 18 Rajput could understand what was happening, in less than a minute, they suffered severe injuries of about a whole company (120 people), out of which 39 were dead1 and the rest injured. Almost everybody of the 18 Rajput and the 10 Bihar were now flat on the ground: dead, injured, or trying to shield themselves from the murderous fire. The battlefield, however, was completely flat and devoid of any cover. There was no cover for the Indian troops. The Indian tanks started to fire, from both the cannons and the heavy machine guns, trying to protect the troops lying exposed on the battlefield.

Before the 18 Rajput could understand what was happening, in less than a minute, they suffered severe injuries of about a whole company (120 people), out of which 39 were dead1 and the rest injured. Almost everybody of the 18 Rajput and the 10 Bihar were now flat on the ground: dead, injured, or trying to shield themselves from the murderous fire. The battlefield, however, was completely flat and devoid of any cover. There was no cover for the Indian troops. The Indian tanks started to fire, from both the cannons and the heavy machine guns, trying to protect the troops lying exposed on the battlefield.