| Cover Story

From Natore

Lost Songs of the Jugi Lost Songs of the Jugi

Saymon Zakaria

Nathjugis, a community of people whose culture and heritage has survived throughout the ages, frequently stage plays entertaining parts of northern Bangladesh. This issue's cover story looks into their origins, the workings of their play including their makeup and attire and their ways of life.

In the remote areas of northern Bangladesh, such as Bogra, Natore, Naogaon and Rajshahi, there are traces of cultural heritage that resembles ideals of Buddhism and meditation. People who practice the arts of this culture are called 'Nathjogi'. According to the acdemics, the area was settled on by Buddhists monks during the Pala Dynasty. Once the Pala Dynasty lost their kingdom to the Sens and the Sen Dynasty began, there was a radical shift in sense of culture and heritage from Jugi to Brahmins, and the original Jugi community became smaller and smaller in number.

|

| A scene from to the "Jugir Gaan" |

Over time, the original religion and culture has evolved to take on its present form, and collectively these people are known as the Nathjugi community. Although these people are more spiritual than religious and despite numerous influences of various other communities and religions over many centuries, strong traces of Buddhism can still be found amidst them. In northern Bangladesh, mostly in Natore and Bogra, there is a frequently staged drama sequence which zeroes in on this particular community, known locally as “Jugir gaan” or “Jugiporbo”.

Jugis or Nathjugis spent the largest part of their life meditating and searching for answers to spiritual and metaphysical questions. The “Jugir gaan” stage drama presents the story of a boy in search of one such Jugi, a master of humanity, who can lead him to the greater truth.

The stage act had mostly been transmitted from one generation to another through memory and practice. Only recently the act has been written down as a play and has taken on a more tangible form.

|

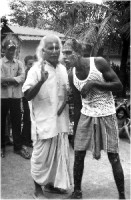

| Jugir (right) and Joigan (Centre) |

This play is often staged at night, in an area lit by hand-held torch. Winter is the ideal season for Jugir gaan and the play is arranged during religious festivities or simply as a form of local entertainment. The stage for the play is a simple mat or pati set at the centre of a plain even land, with four bamboo sticks stuck in the ground at the corners to define the boundary of the stage. The audience sits on all sides, circling the stage. The actor playing the Jugi usually wears a white Panjabi or Fatua and a Dhoti, whilst the second cast member, an adolescent boy (balok das) wears a towel (gamcha) and a sleeveless t-shirt (usually ones that are worn as an undergarment).

The Jugi usually has long flowing white hair and looks much like a Sufi. White marks adorn his two earlobes and is extended from his forehead to his nose. The appearance of the second cast member, Balok das, is even more interesting. He has white circular markings all over his face and feet. One of his eyebrows is adorned in white while the other is marked in regular black. Although the third cast member plays a female character known as Joigan, the character is played by another male dressed in a colourful saree. The fourth and last character, Shyamdas, wears ordinary village clothes. Any room in a nearby house can serve as the green room for the show.

|

| Jugir and Balok das |

The play begins with music or 'bondona'. The bondona ends with the Jugi and Balok Das exiting the green room and walking up to the stage singing along the way. At the very centre of the stage, the musicians take up their positions from the very beginning and the Jugi and Balok Das walk around them as they sing and act. The performance involves a bit of everything - a bit of dancing, a bit of dialogue and quite a bit of music and singing.

This play represents the last remaining art that is still active and is connected to a group of people who had inhabited and taken refuge in northern Bangladesh for centuries. But, unfortunately, its spirit has weakened in the wake of modernization and urbanization. Although there are many palakars who used to arrange such plays in Rajshahi, Natore, Naogaon, Bogra, and Kurigram areas, their enthusiasm is on the wane. There is even a handful who has not arranged a play in over four decades!

Of course, it is not for the palakars alone to shoulder the responsibility of keeping alive this age-old tradition. The weight of such a responsibility is much too great for such a small group to bear. Keeping traditions such as the Jugir Gaan alive is a responsibility we all share, a collective responsibility as much as it is a source of collective enjoyment.

Translated by Zahidul Naim Zakaria

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

Lost Songs of the Jugi

Lost Songs of the Jugi