Industrial policy analysed

Enam A. Chowdhury

|

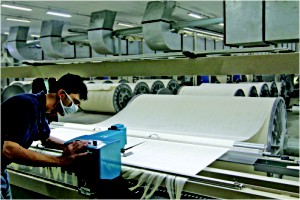

Photo: Amran Hossain |

AN industrial policy has been announced, and the Hon'ble Prime Minister has spoken on the attainments of her government over the last two years. As we review the steps taken in the field of industrialization, we do not really see any reason to be complacent about. In the PM's speech, there is no mention of industrial policy related growth, as there has been hardly any. There is no evidence that the country has been put steadfastly and robustly on the road towards industrialization. Rather, one cannot but feel the absence of a positive coordinated policy with a sense of direction and clear-cut approach towards achieving well-set-up targets. An industrial policy has been announced, but this reads more like a college-essay on industrialization and not a document that contains specific guide-lines that a nation would follow step-by step. This does not detail measures to be taken by all related agencies and sectors for facilitating industrialization.

The industrial policy should have been presented in the perspective of national long-term planning. It has been mentioned in the objectives of the policy that this would make the attainment of the millennium development goal (MDG) possible by creating a modern and prosperous industrial sector without detailing the measures; it states that by following short, medium and long-term programme of action, the unemployment and poverty level will be reduced to half by 2017, and that the GDP growth would be made 8% in 2013 and 10% by 2017, so that by 2021 Bangladesh becomes a middle income country. Sounds like just a pious wish, almost like an effort to hood-wink people.

In reality, the industry sector growth was 6% in FY 2010 down from 6.5% in FY 2009. In manufacturing industry, the decline has been more steep -- it has come down to 5.7% compared with 6.7% in FY 2009. The combined impact of lower growth in diverse export industries (except perhaps RMG and shipbuilding) and the hindrances caused by shortages in power and energy production, inadequacies in transportation sector, absence of rule of law, mounting corruption, and political-industrial unrest was palpable. The industrial policy cannot be viewed in isolation, and successful implementation of the same will have to ensure meeting the challenges in the related areas. A proper policy is expected to be realistic and not devoid of practical considerations. There is no denial of the fact that there is grave fuel and energy crisis in the country, no new gas connection is being given now, LPG prices are on the rise, load-shedding is increasingly becoming unbearable, and as the predictions go, the next Boro season will see the worst of it. Actually in the industrial policy that has been declared, there is no indication as to how the hindrances will be overcome, and how the policy will be integrated with the over-all national planning. Say for example, in the objectives of the policy, it has been mentioned that by 2021 AD, the industrial sector will be so developed that its share of national income would be raised from 28 percent to 40 percent and in the employment sector, the share will move up from 16 percent to 25 percent. The indications as to how measures would be taken to reach these goals are mostly vague, inadequate, and impractical. That the small loans being successfully given by Grameen, Brac etc to ignite individual motivation in productive sectors has been completely ignored. Rather, the recent concerted effort of being made by the government party circles to dampen the great national and international enthusiasm and support generated by Grameen to initiate individual and group efforts by the very poor to eradicate abject poverty at the grass-root level are not only disquieting and disappointing, but astounding as well.

|

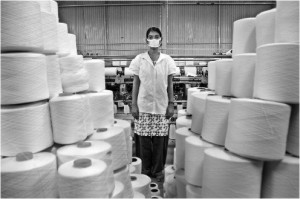

Photo: Amran Hossain |

Education undeniably is at the root of all progress and growth, but the role of informal education and the impressive and internationally recognised contribution of Brac in this regard have been totally ignored in the educational policy and elsewhere. It seems that the government party is bent upon hitting our sense of national honour and pride. That these would thwart grass-root initiatives to contribute to productivity seems to have been totally forgotten.

There are a number of other inherent contradictions as well which need to be pointed out. It is said in the policy that the private sector would be the engine of growth, and the main feature of economic growth would be private-public partnership. At the same time, the government has, more or less, halted the hitherto successful process of privatization, and at the same time, it has failed to rejuvenate the public sector.

The loss-incurring public-sector enterprises are continuing their operations at a very high cost, and there has been almost no new public sector investment. It has been said that import-substitute industries and diversified export-oriented industries will be set up. But the commercial and other relevant policies do not appear to be at all helpful in this regard. RMG, leather, ship-building and IT industries are sectors where there have been growth and greater potentials are there. But in these sectors also, the government should have been, and will have to be more categorical and specific in the way it intends to extend support and co-operation. In some cases, the government will have to be effective in tackling industrial unrest. Mere constitution of industrial police force will not be enough. It would be better if the industrial police is put directly under the (civil) Deputy Commissioner who would keep himself abreast of labour disputes and political involvements, and should be in touch with labour leaders, people's representatives, factory owners and social high-ups. In the PM's speech, she only mentioned -- "We have taken up public-private partnership (PPP) programme." But what has been done or what the government intends to do has not at all been indicated. Ship-building industry of Bangladesh is now getting orders from Japan and Europe for building oil tankers, food grain carriers, deep-sea fishing trawlers etc. Industrial policy does not contain any supportive measure for these export industries. The over-all investment scenario remains depressed and there is hardly any positive sign of FDI in the manufacturing sector.

The situation in the energy sector continues to be very dismal. The government has not approved new connections for gas and electricity to new industries for quite some time. There is a lot of wastage in many of the poorly-run partly-closed state-owned enterprises. No new gas field has been effectively explored. The rental power plants are yet to go into production, and even when the questionable plants go into production improvement will not perhaps be significant. There is no doubt that with such energy crunch there is hardly any possibility of any investment -- whether domestic or foreign, in the industrial sector. A recently-held nation-wide survey conducted by the International Finance Corporation amply indicates that. Highways and ports require gigantic improvements and extension, so that adequate infrastructure can really play a supportive role for industrial development. Unfortunately, the government without paying attention to these areas is borrowing costly money from India for developing infrastructure only for specifically facilitating Indian transit. It is also planning to invest on a huge scale for developing an international airport in Arial Beel the economic return of which will be minimal. That would also be environmentally harmful, will destroy extensive wet and farm land and will cause homestead and livelihood loss to a great number of people. Rather, development of existing international airports and connecting them properly with industrial growth centers and tourists destinations, and making Cox's Bazar airport suitable for wide-body plane landings would have given much more economic returns and directly helped in development of tourist industry. This also would have contributed towards development of infra-structure, a pre-requisite for successful implementation of the industrial policy.

|

Photo: Amirul Rajiv |

The industrial policy, as announced by the government, unfortunately does not reveal in concrete terms as to how it would promote the growth of private sector industries and encourage public-private partnership (PPP). That the government has got nothing much to say with regard to industrialisation or the role of private sector was evident in the government sponsored supplement on "completion of 2 years of change" where it received hardly any focus. The industrial policy should have also given some indication of steps to be taken for expansion of market of industrial products. Governmental efforts in this regard have not been successful as yet. Even the much expected and promised duty waiver for exports of 61 products to India has not been obtained.

The biggest drawback of the policy and the government's deficiency in moving towards industrialization is its failure to determine the path to be taken. If the private sector is expected to be the engine of growth, then definitely privatization and public-private partnership should have been given their rightful place in the policy, and the mode of their implementation clearly laid out, detailed and prioritized. In a recently-held seminar, the President of MCCIA Mr. M. Anisud-Dowla said, "the industrial policy is full of contradictions. The number of sick industries has increased because of the inefficient public sector.” He advocated that the non-profitable SOEs should be privatized.

If we leave out the last two years, the record of privatisation in Bangladesh has been encouraging, and in comparison to the efforts of other developing countries, the Bangladesh initiatives have been pretty much of a success from the outset. The Privatization Commission in 2002-2006 privatised almost all the SOEs which had been entrusted to it, and were free from encumbrances like court orders. The process adopted were also transparent and free of all allegations of corruption, politicization and inefficiency. Only the monitoring activities of the privatization commission needed strengthening.

However, the current promising initiatives of the privatization commission have now been stalled by the ambivalent government policy and contradictory programmes followed by different ministries. The ministries should concentrate on running their enterprises and not liquidate them. Disposal of the irreversible loss-incurring SOEs which are causing hemorrhage to national economy should be done by an authority which will have no vested interest and has the requisite expertise and proven commitment. Privatization is, however, not meant for just closing down state-owned enterprises, but it should be taken as a tool for boosting activities in the private sector as a part of overall national planning. It is expected to devise ways and means for introducing and inducting private elements in governmental initiative with a view to expediting the process of industrial growth. The agenda for industrialization through private sector participation should clearly and unambiguously be based on this realization and consideration. As a matter of fact, privatized SOEs would have a few added advantages, which a new industrial undertaking, particularly in the private sector, would now be badly lacking. These are the much-needed land, infrastructure support which would include power connections and qualified labour-availability.

|

Photo: Wahid Adnan/Driknews |

There is no denying that in the whole range of manufacturing activities which are critical to the growth of the economy, private enterprise is not forthcoming or is coming at a very low and hesitant pace. The government is not coming up, or is not in a position to come up to initiate industrial enterprises in areas where private initiative is lacking or shy. Bangladesh is now left with a distressingly narrowing manufacturing base where very little diversification has taken place outside the RMG which is now our leading industry and export earner. Prof. M. M. Akash correctly recommends adoption of a policy based on pragmatic privatization, policy which should take into account the over-all necessity of the economy and the imperatives of industrial growth, and chalk out a systematic sector-wise programme for private participation. This is what he calls "The case for pragmatism." India's Planning Chief Montek S. Ahluwalia writes in his article on 'Economic Reforms in India since 1991" (Published in the Journal of Economic perspectives -- Volume 16 No 3) -- "An important recent innovation, which may increase public acceptance of privatization, is the decision to earmark the proceeds of privatization to finance additional expenditure on social sector development and for retirement of public debt. Privatization is clearly not a permanent source of revenue, but it can help critical gaps in the next five to ten years while longer-term solutions to the fiscal problem is attempted." It will "at least eliminate the recurring burden of financial losses."

The government of Canada has a splendid record of public-private partnership. It's policy for privatization states, inter-alia, "When they (privatization initiatives) are part of a broader effort to improve public finances, such initiative can contribute to fiscal consolidation by reducing budgetary requirements and debt-levels. When structured to stimulate improvements in economic efficiency, privatizations are likely to enhance the economy's performance, and thereby produce long-term economic and budgetary gains.

Industrial policy should have been a beacon for industrialization and economic growth. Unfortunately, it has not been so. It requires urgent modifications.

The writer is former Chairman, Privatisation Board.