Charting course for education

Manzoor Ahmed

|

Photo: Hasibur Rahman Bilu |

GREAT strides have been made in education, particularly in the last two decades. Almost all children now enroll in the first year of primary education. Uniquely among poor countries, gender gap in enrollment in primary and secondary education has been eliminated in Bangladesh. Along with the expansion of the public provisions, the private providers have become major actors in tertiary and vocational-technical education. Yet, Bangladesh (along with several other South Asian countries) is not on track to achieve the modest 2015 Education for All goals, according to the EFA Global Monitoring Team of UNESCO. Deficits in aspects of access to basic education and very high dropout rates at all stages persist. Establishment of quality standards and enforcing these in the entire education system remain major concerns.

A new education policy adopted in 2010 and the political pledge of the government reflected in Vision 2021 provide a framework for shaping objectives, priorities and strategies for educational development for the nation. The sixth five year plan (2011-15) under preparation, following the decision of the government to re-institute the five-year development planning mode, can be the institutional mechanism for resource provisions, coordinated action, and placing all reform and development efforts within the agreed framework of the new education policy.

As Bangladesh enters the fifth decade of its independence, it aspires to join the ranks of the middle income countries, promising prosperity with equity for its people. Progress in education will determine if the envisioned future will be built.

How have we fared?

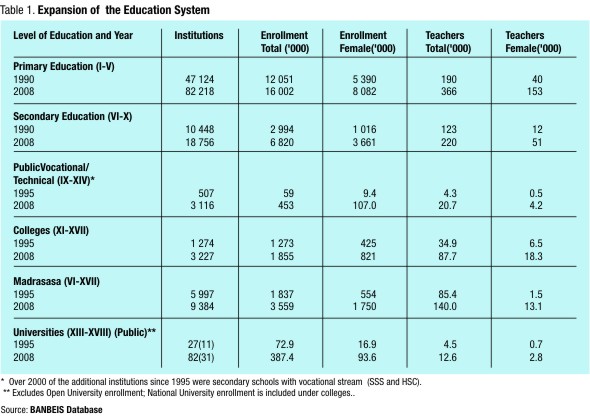

The educational system in Bangladesh consists of some 150, 000 institutions, 30 million students and about one million teachers. Primary and secondary level institutions naturally form the bulk of the system with about 18 million students in primary education including madrasas and non-formal programs and 11 million students at the secondary level including madrasas (BANBEIS data).

The 1998 Human Development in South Asia Report, prepared under the guidance of the late economist Mahbubul Haque, noted “conscious government policy” in Bangladesh that helped to accelerate progress in basic education, achievement of “near gender-parity in primary enrollment”, and a “dynamic role of many NGOs, grassroots community organizations, and institutions of civil society” (pp.57-58).

Having mentioned the formidable educational challenges facing Bangladesh, the report concluded optimistically that “If the Bangladesh Government can earmark a higher proportion of its GNP for education and if NGO and community efforts are further encouraged and supported, the country is poised to make a major breakthrough in the field of education” (p. 59).

A critical look at the recent past shows that the promising beginning made in the early 1990s has more or less kept pace with the need for quantitative expansion of the system; and gender parity in primary and secondary education enrollment has been achieved. The promise of a major breakthrough in respect of quality of education, equitable participation and mobilizing and using adequate resources effectively, however, has not been fulfilled.

It can be seen from Table 1 that primary education enrollment has increased by 50 percent, and secondary enrollment has more than doubled since 1990. There has been faster growth in technical/vocational and tertiary education since 1995, starting from a relatively low base. Madrasa enrollment also has increased rapidly particularly at the secondary and higher secondary levels. There has been more than a proportionate growth in female enrollment at every stage, but disparities continue in vocational/technical and tertiary education.

The basic education deficits. There is an upbeat official view of the situation in Bangladesh. Government statements cite the statistics of 103 percent gross enrolment rate in primary education and parity in enrolment of boys and girls at the primary and secondary levels (DPE data). Officials also note with pride the stipends programme for up to 40 percent of the students in rural primary schools identified as poor, stipend and tuition exemption for girls in rural secondary schools, and distribution of free textbooks in primary schools. These measures have indeed resulted in enrolment growth, in general, and of girls, in particular.

However, a dropout rate of about half of those who enter class one by the time they reach class five and over 80 percent by the time they reach class ten turn the general education system into a veritable wasteland both in terms of use of public and (very substantial private) resources and fulfilling children's right to education. The large majority of the children of Bangladesh remains deprived of basic education an untenable and unacceptable situation for a country aspiring to join the ranks of middle-income nations.

It is the children of the very poor, both girls and boys, those living in inaccessible areas such as chars, haors, and hills, children with special needs, and children of linguistic and ethnic minorities, who are particularly vulnerable to being excluded.

Multiple provides and inequity. Both primary and secondary levels consist of multiple providers government run schools, government assisted primary and secondary schools and Madrasas, vocational stream and schools at the secondary level, and English medium private schools. The public system (both directly government run and government assisted) caters to the large majority of children over 80 percent at the primary level and over 95 percent at the secondary level. However, common minimum quality standards do not apply to these provisions. Public expenditure, one of the lowest on a per student basis even among the least developed countries, is not allocated with criteria for ensuring quality and equity in the system. As a result, students going to different institutions, end up with highly uneven provisions, and the learning outcomes are on the whole very poor for most students.

The small number of expensive English medium schools and a protected enclave within the public system (cadet colleges, laboratory schools, and model schools, which receive more favourable public support than the regular schools) serve the privileged. Entry to the “protected” public institutions is presumably based on merit and equitable. But, it is well- known that the dice in society's roulette rolls in favour of those who can afford the price of extensive private coaching and tutoring and families with educated parents who offer a supportive home environment for the potential candidates for the limited places in the better quality public sector institutions. One consequence of this situation is that the politicians, bureaucrats, businessmen and other well-heeled people in society, who can send their children to the English medium and the privileged public system schools, have no personal stake in the performance of the general public education system.

In respect of learning outcome, the key quality criterion, government's own assessment done by the Directorate of Primary Education corroborates Education Watch and other studies that a quarter of primary education completers are likely to be without acceptable literacy skills and one-third of the students would be without essential numeracy skills. Remember that the completers are already the lucky minority who survived up to class five. This is not surprising in a system with 90 percent of the primary schools run in two daily shifts. On average, the specified learning time is around 500 hours in a year, about half of the international standard. The average student teacher ratio is 50 to 1. A pedagogically acceptable ratio is half of this.

The literacy debate. A contentious issue is the rate of adult literacy in the country. The Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MOPME) launched in 1997 the Total Literacy Movement (TLM) to “eradicate” illiteracy in a decade and declared that the adult literacy rate (for population of age 7 and over) had reached 64 percent by 2002. Independent evaluation including national sample surveys, applying objective methodologies, carried out by Education Watch research team and others revealed that the rate was under 50 percent. These studies also showed a major gap in rates for urban and rural areas and for men and women in the range of 10 to 20 percentage points ( Education Watch Report, 2004).

MOPME apparently is prepared to launch a TLM type campaign to fulfill a political pledge to “ eradicate illiteracy” from the country by 2014. It has so far found it difficult to present a convincing programme and mobilize funding from development partners and even the Ministry of Finance.

The body of international experience of more than a half century provides definite lessons in this regard. It is meaningless to launch a campaign and aim at only familiarity with the alphabet and the tokenism of signing one's name. Anything beyond that to equip people with the capacity to access relevant knowledge and information, improve their life and look at the world critically means the creation of a learning environment and opportunities for continuing lifelong learning in every community. As Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator, famously said, literacy is about reading the world, not the word.

The laudable political commitment of the government needs to be translated into targets and programmes to create a nationwide network of permanent community learning centers involving the local government and community organizations. These centers would be the building blocks of lifelong learning offering a menu of learning according to people's needs including literacy and post-literacy courses.

|

Photo: Star |

Key problem access with quality and equity

The problems of access and quality at all stages of education are symptoms of a deeper malaise that has developed through decades of neglect. In fact, a system that originated in the colonial era with its inherently restrictive perspective was pressed into service with only patchwork modifications to meet the demands and aspirations of human and national development of an independent nation. For a nation that has to rely primarily on its human resources to fulfill its vision of progress and development, the failings in education constitute a critical risk for all its development endeavors.

The first serious attempt to envision educational development and provide a policy direction for a newly independent nation was the 1974 Qudrat-e-Khuda Commission Report. The fateful events of August 1975, when the Father of the Nation was assassinated, derailed democratic evolution of the new nation along with a derailment of normal development in various spheres of national life, including its education system. At least half a dozen education commissions and committees were appointed since then by various regimes, but none were followed up by serious implementation efforts.

Ad hocism prevailed and externally driven projects without the underpinning of properly articulated national education development priorities and strategies dominated educational investments. The new education policy adopted by the Parliament in December 2010 is another attempt to instill a sense of direction in the education system. The litmus test that it will not suffer the fate of past policy initiatives will be the steps taken and the determination shown by the government to implement the policy, with essential adjustments in the course of doing so.

The drift in educational development is illustrated by the history of the vital sub-sector of primary education. The nationalization of primary education in 1973 was undertaken with the noble aim of expanding and improving primary education access for all children, and expressing state commitment to provide basic education.

The unintended consequence was the severing of accountability and connection of school with community and parents. The government soon discovered that it could not (or would not) provide the resources for running a fully government system for all children. Moreover, it was realized, by the way the nationalized system performed, that the central government could not manage effectively a far-flung system that would guarantee acceptable learning outcomes for most, if not all children. Thus arose the unstated policy of letting registered non-government schools (RNGPS) and ibtidayee madrasas serve the increasing numbers of primary age children. The number of government primary schools remained around 37,000 since 1990, whereas the total number of primary institutions increased to over 80,000 in the following two decades.

While the system expanded, quality and equity suffered, as more of the children of the poor found themselves in the less endowed RNGPS and madrassas, compared to the government schools, in a poorly resourced total system.

A unique feature of Bangladesh primary education is the large non-formal primary education programme pioneered by BRAC. Over a million children, dropout from or never- enrolled in formal school, majority of them girls, were offered an equivalent of primary education. There was over 95 percent completion, and in the 2010 primary completion examination (Shomaponi), 99 percent of the BRAC NFPE children passed. The large majority of them go on to the secondary school. However, it has been so far found difficult to incorporate some of the strong features of the non-formal approach into the mainstream.

The new education policy recognizes the reality of the diverse providers in both primary and secondary education that has arisen historically. It attempts to reconcile the diversity with the obligation of the sate to ensure quality basic education for all children by establishing common minimum standards of provisions and core curricular contents in all types of institutions. The core content and objectives can be supplemented by additional contents according to needs and demands. This seminal policy item will have a profound impact on quality with equity, but will pose formidable challenges in implementation.

Speaking of Shomaponi, a national primary education exam leading to a primary certificate was introduced in 2009. This provides a standard measure of learning in a system with diverse modes of delivery. In 2009, 89 percent of the examinees passed the exam, and in 2010, the pass rate was over 92 percent. How does this jibe with the poor performance of schools and children noted above? It must be remembered that the students in class five represent half or so of the students who had started class one five years earlier and did not drop out. Moreover, some 10 percent had registered for the exam in 2010, but did not sit for it. Another 8 percent failed. The high pass rate, therefore, by itself can be misleading.

The shomaponi and the recently instituted public examinations JSC and JDC (junior school certificate and junior dakhil certificate at the end of grade eight) are positive steps. But to make them a useful assessment tool for performance of students, schools and the system, there is need for a continuing and systematic research and development effort. For example, a perusal of the test items show that many of these are a test of capacity to memorise and reproduce certain textbook content rather than one of skills and competencies.

Some would argue that a competency test need not be on all the subjects in the syllabus. It could be only for competency in language, math and science, as it is done in assessment of learning at key stages of elementary education in UK and elsewhere. It is pedagogically and ethically questionable to create an atmosphere of intense competition and brand some children as low performer and even failure at age 11. The validity and reliability of the tests whether they actually measure competency and do so consistently for all children is a question mark as noted. Moreover, the “poor performance” of some students is indicative of a poor job done by the school for which the students should not be penalized. There appears to be no special effort or plan to deal with the significant numbers who fail or are pushed out from class five.

Priorities for realistic action in the sixth plan

Various analyses of the education sector ( viz., sector reviews some years ago supported by the World Bank and Japan Bank for International Cooperation), independent studies (such as the Education Watch annual reports since 1999), the background papers for the sixth plan, and reports and documents pertaining to donor-supported development projects in education (such as those related to the Second Primary Education Development Program and the Secondary Education Sector Improvement Program) collectively provide a run-down of the education system deficiencies, some of which have been discussed above.

A longer term view of the education system priorities and needs, based on a historical perspective, can be derived from existing analyses and assessment. They point to inter-connected areas which must receive attention in constructing a vision for educational development in the light of the new education policy. These need to be incorporated in the targets and strategies of the Sixth Five Year Plan, currently under preparation. These priorities include:

* Universalization up to grade 8

Eight-year UPE is achievable and must be achieved in a decade, as proposed in the new education policy. A coordinated upazila-wise assessment and planning is essential for this purpose. A majority of primary schools may continue as 5-grade feeders to selected 8-grdae schools or to 5 or 7 year middle-cum-secondary schools operating through necessary local coordination. The key concern is to ensure that the present quality deficits of primary education are not extended to grade 8.

* Equity with quality in primary and secondary education

Historically evolved multiple provisions in primary and secondary education have served specific needs. Enforcement of common quality standards and core curricula across the diverse provisions can best serve the quality-with-equity principle, which should be the focus of the sixth plan. Governance and financing strategies must support this principle. Upazila-wise systematic planning and financing with local government and community involvement, and mid-day meals for primary level children, should be part of these strategies.

* Teachers as key to quality

The teacher has to be seen as central in the strategy to improve educational quality. Bold and creative measures are needed to attract talented and inspired young people to teaching, keep them in the profession and create a critical mass of talented teachers in the education system. A ten-year plan involving a hundred degree colleges for enrolling bright young people in a degree program with education as a subject can be a key pre-service program approach for future teachers. A national education service corps can thus be created with stipends and promise of better remunerations on condition of at least five-years of service in the public system. Quality of provisions and pedagogy in the selected colleges also has to be ensured. The Diploma-in-education course in PTIs, under development at present, can be a complementary initiative.

* Common core contents in primary and secondary education

A qualitative transformation in teaching the identified core skills and competencies in all categories of primary and secondary institutions should be a priority. Short term measures such as contractual appointments and extra incentives for capable instructors in math, science, English and IT should be introduced; longer term measures would include special pre-service programs (as mentioned above). Strong bilingual competency in Bangla and English for all students completing the secondary stage should be a core objective building the foundation of Bangla competency by fifth grade and similar English skills at the secondary stage. Mobile phone operators, IT multi-nationals, Internet service providers and other businesses should be persuaded and given incentives to “adopt” schools to support IT instruction and IT-based improvement in pedagogy.

* Transforming vocational and technical education

Addressing the paradox employers' complaint about shortage of skilled workers and unfilled places in vocational institutions and sometimes unemployed graduates have to be addressed by redesigning the role of the public sector in vocational/technical education and training through new modes of collaboration that involves employers and NGOs in public institutions' operation and management. This measure should be supported by government encouragement and incentives for private sector training institutions, apprenticeship and on-the job training. Particular attention is needed to making training responsive to market demands, locally and overseas; skill development for the informal economy where the large majority of workers are employed; and overall attention to quality of training by applying “external efficiency” criteria. It should be ensured that a draft skill development policy that has been prepared under the aegis of the new National Skill Development Council address the critical issues and necessary steps are taken to implement the policy.

* Two aspects of decentralization

Decentralization of governance through empowered local government is a key political commitment of the government. But decentralization is no panacea in a corrosive political culture of patronage and corruption. A substantial pilot program should be launched under the sixth plan to try out two key aspects of decentralization in education - devolution of authority and resources to local levels involving local government and devising institutional models with greater academic, management and budgetary responsibility with accountability at the institutional level. The goal will be to learn about decentralization that works and that can be widely applied.

* Literacy and NFE in a life-long learning perspective

Literacy and non-formal education must be conceptualized as integral components of life-long learning opportunities made widely available. A nationwide network of community learning centers under local government auspices with active involvement of NGOS and community organizations should be the vehicle for life-long learning, complementing formal education. Promoting functional skills and meeting genuine learning needs, rather than mechanistic literacy targets, should be the aim, and programs should be designed and objectives defined accordingly.

* Consolidating quality in tertiary education

Although participation in tertiary education remains low, more harm than good will result from expanding tertiary education, unless acceptable quality can be ensured. A moratorium in principle should be applied on establishment of new institutions until acceptable standards are achieved and ensured in existing ones. The sixth plan's focus should be on applying rigorously already established quality standards and consolidating and rationalizing existing institutions, before investment is made on expansion and new institutions

* Financing strategy to support quality with equity

A goal of 4 to 4.5 percent of GDP as public education expenditure should be the target by the end of the sixth plan. Financing criteria and principles should be established and applied to support the objectives of quality-with-equity. These would include Upazila-wise capitation formula and institutional control of resources. Substantial new resources should be directed to teacher incentives and raising status of teaching as a profession and other quality improvement inputs.

There are no magic bullets for improving educational systems. There is no alternative to patient and system-based work simultaneously on several fronts. The critical concern is that these efforts should result in cumulative progress rather than periodic regression. The new education policy provides the opportunity and poses the challenge to move forward with genuine stakeholders participation, mobilizing and using resources to maintain a threshold of resources necessary for acceptable quality in the education system.

The writer is senior adviser at the Institute of Educational Development, Brac University and vice-chair of Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE).