Madrassa education needs reform

Ishfaq Ilahi Choudhury

|

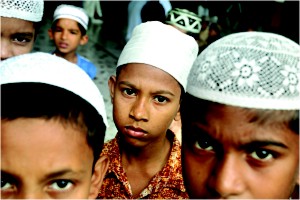

Photo: Amirul Rajiv |

Genesis of madrassa education

The word 'Madrassa' means a place where 'darse' or lessons are given, literally a school. In the heydays of Islamic civilization (7th - 13th century), there were Madrassas in Baghdad and Cairo that were centres of excellence in spiritual and temporal learning. While Europe was in the “Dark Age”, these madrassas attracted students and teachers from all over the globe. However, the Mongol invasion in the 13th century resulted in the sacking of great cities, including Baghdad (1258 AD), destruction of libraries and mass-murder of intellectuals. While a pall of gloom hung over the Islamic world, the pursuit of knowledge was replaced by a fatalistic philosophy of predestination. The society, bereft of intellectuals, was dominated by the clergy whose edicts became law.

Madrassas gradually became a place exclusively of religious education. Although there were flickers of revival during the Ottoman period from the 15th till the 17th century, the old glory never returned. The madrassas in Grenada and Cordova in Andalusia (Spain), which escaped Mongol invasion, acted as beacons for the scholars till those too fell to the Europeans (1599 AD). With the colonial occupation of much of the Islamic world in the 18th and 19th centuries, madrassas came to symbolize traditional Islamic teachings while schools, colleges and universities represented the dynamic and challenging frontiers of new knowledge. The Arabic word 'kitab' which literally means books, came to mean religious scriptures. Similarly, the word 'Alim' that means “a learned one”, came to mean a Madrassa graduate.

The first modern Madrassa was established in 1781 in Calcutta by Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India. “Madrasa Aliya”, as it was called, was established chiefly to produce Muslim officers for running the revenue administration and judiciary. Thus, the syllabus focused on the Islamic law and jurisprudence. English, mathematics and natural sciences were introduced later despite opposition from the Muslim elites. The madrassa was later divided into two sections namely, Anglo-Persian Section that dealt mainly with English and other secular subjects and Arabic section that taught primarily religious subjects. During partition of India in 1947, assets of the Calcutta Aliya Madrassa were divided between the two states. The leaders of the then East Pakistan opted for the Arabic section of the Madrassa which was transferred to set up Dhaka Aliya Madrassa.

Calcutta Aliya Madrassa produced a galaxy of Muslim intellectuals, but the institution remained a suspect in the eyes of the Ulemas. After the Great Mutiny (1857), the Muslims of India were divided in two main streams. The conservatives set up “Darul Uloom” madrassa in Deoband, India in 1866, while the modernists established Anglo-Oriental College, later Aligarh Muslim University in 1875. Both these institutions, located within 50 miles of each other, played pivotal role in shaping the history of the sub-continent. While Aligarh represents modern education blended with Islamic traditions, Deoband's curriculum is based on the 17th century Islamic syllabus known as Dars-e-Nizami. There are thousands of madrassa in South Asia that follow Deoband syllabus, commonly known as Deobandi Madrassa. Deobandi madrassas in Pakistan, especially in Karachi and the FATA region, have evolved into Jihadi madrassas, recruiting students from all over the world, training and motivating them to wage a global Jihad.

|

Photo: Amirul Rajiv |

Growth of Madrassas

The madrassas grew slowly in the then East Pakistan; by 1971, there were about one thousand Aliya madrassas. These madrassas functioned under the control of the Madrassa Board and followed Govt. approved syllabus. There were also few thousand Deobandi madrassas known as Quomi Madrassa which were unregistered and unregulated. Since the early 1980s, there had been a sharp increase in numbers of Aliya and Quomi Madrassas in the country. By 2008, there were more than 9000 Aliya madrassas in the country. While there were about 12000 students in Aliya madrassas in 1971, more than 3.5 million students are now enrolled in these institutions. There is no statistics about the Quomi madrassa, but it is estimated that their number as well as the enrollment is equal to, if not more than, the Aliya stream. While Govt. had gradually modernized the Aliya stream of madrassas by including natural and biological sciences, social sciences and business studies, the Quomi madrassas remained outside any governmental control or supervision. While Aliya graduates are now able to compete and get selected in the universities, medical or engineering colleges, those from the Quomi madrassas have no access to employment other than becoming an Imam or Muezzin of a mosque or become petty shopkeepers etc. Many become religious instructors, few might get together to open another Madrassa or start a mosque, thus adding to the proliferation of mosques and madrassas in the country.

Between 2000 to 2008, while the number of Primary school students fell from 1.76 crore to 1.60 crore and the secondary school students fell from 76.4 lakh to 68 lakh, the number of Aliya madrassa students went up from 12 lakh to 17 lakh. The picture is more dramatic if viewed from 1970 onward. From 1970-2008, while the number of secondary schools grew by 300% and the students' enrolment went up by 500%, the Aliya madrassas grew by 600% and the students' enrolment went up by 1256%. When one adds the huge numbers of Quomi madrassas and their students, one can visualize the size and strength of madrassa stream. Beside government patronization to madrassa education by post-1975 governments, generous donations from home and abroad, especially from the Gulf Arab states, helped start a boom in madrassa education that continues today. Inadequate government funding for mainstream education is an important factor for the rapid growth of Madrassa system as an alternative form of education. Poor children who cannot afford to go to mainstream schools often have no alternative but to enroll in a madrassa where education is not only cheap, but where, if one is lucky, might end up with free food and lodging. Newly emerging Cadet Madrassas, however, cater to the newly-moneyed Muslim elite who seek Islamic education with an elitist touch for their children. In sharp contrast with the Madrassa boom, there has been a sharp decline in science education in Bangladesh. The number of students appearing in science group in secondary examination reduced by more than 50% in less than a decade.

Current state of Madrassa education

While Aliya madrassas are functioning only in Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, Quomi madrassas are widespread across South Asia. The two madrassa streams add to the multiple streams of education in the country. Bangla and English medium, US High school degree (GED), and now Cadet Madrassas add to the multiplicity and confusion that exists in the secondary education sector. At the primary level the madrassa stream offers 5 years of Ibtidaia, which is quite close to mainstream primary education. Aliya madrassas offer Dakhil and Alim degrees after 10 and 12 years of education. These degrees are equivalent to, but not really equal to, SSC and HSC respectively. The differences exist in the relative weightage of the subjects. For example, while the madrassa students study Islamic laws or Arabic extensively, their knowledge in Bangla, English or in natural or biological sciences would be limited because of abridged courses offered to them. It is no surprise, therefore, to see so few madrassa students in engineering, medical or hard science subjects like Physics, Chemistry or Mathematics. Students who wish to pursue a career, therefore, skim through the religious subjects that they know will be of little practical use, but concentrate on the secular subjects. At present, Govt. spends almost 12% of the education budget on Madrassa education compared to about 24% for the mainstream secondary and higher secondary education. Our meager resources would have been better utilized if we could have a single stream, instead of multi-stream as at present.

Until a decade ago, the Quomi madrassas taught virtually nothing other than religious scriptures and their varied interpretations. Recently, because of the market demand and Governmental pressure, Quomi madrassas have started teaching Bangla and even English language, mathematics, natural and social sciences etc. Yet, these institutions generally suffer from endemic shortage of quality teachers, text books and infrastructures. This stream starts with a 3-4 years of Hifzul Quran where children memorize the Quran. They then move to Ibtidaia where Arabic, in some cases Persian and/or Urdu, is taught along with Bangla, mathematics and social studies. The next stages are Mutawasita (Secondary) and Sanubiya Ulya (Higher Secondary) where Arabic, Persian/Urdu languages along with Quran and its interpretations, Hadith, Sharia laws etc occupy the major part of the syllabus, while Bangla, English, Mathematics, Islamic History etc get less attention. Virtually missing are the modern natural and social sciences, commerce and technical subjects. Even classical Arabic or Persian languages that are taught have little practical value. The Quomi system suffers from lack of standardization and uniformity in text books, examination system, teachers training and qualification. Although an institution called Befaqul Madarrisil claims to hold central examination for these madrassas, many large madrassas do not recognize this institution and prefers to have their own examinations and standards. Thousands of students coming out of the Quomi madrassas each year, therefore, have virtually no saleable skill in the market place. However, if one owns a madrassa or a chain of madrassas or be Imam or Khatib of an important mosque, one can exercise enormous power in the public arena. With the increasing Islamisation of the society, many become preacher holding Waaz Mehfils, some are employed in the TV to speak on Islam, some are sought to issue Fatwas (Edicts) on various issues. For the rest, life can be an endless cycle of poverty and drudgery. They are targeted by those seeking to recruit desperate young men ready to blow themselves up in order to destroy a society that, in their view, shuts all windows of opportunities on their face.

Madrassa Education vis-à-vis Education in the Islamic World

The proponents of Madrassa education in Bangladesh claim that it truly reflects the Islamic tradition. However, history does not support the claim as described. In countries, such as Turkey, Egypt or Malaysia, all religious schools are subject to government control and supervision. All students get a basic secondary education and the enrollment is only enough to cater to the needs of the religious institutions. Nowhere these schools churn out graduates in their hundreds of thousands. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, which many would view as a theocratic state run by the Mullahs, there is no Madrassa stream. In primary level, the students have two periods of the Quran and three periods of “Religion and Ethics” in a thirty-six periods-a-week schedule. In the secondary and the higher secondary stages there is no Quranic class, instead “Religion and Ethics” takes three periods in a week. After that, students can branch out to a number of career paths. Those who wish to take up Islamic studies can get admitted in some of their excellent Universities that offer a whole range of religious subjects. The subject “Religion and Ethics” continues with three classes per week in higher learning, including technical, medical, but there is no examination and the subject is a non-credit course. Madrassa system of education in Bangladesh is unique in the world.

Education Policy 2010 and the Madrassa Reform

It has been customary for every government to set up an Education Commission soon after assuming office. These Commissions often produced volumes of paper works, seminars and discussion sessions, ending up with little progress on substantive matters. The last Education Commission set up in 2003 was called Moniruzzaman Mia Commission. With a strong Islamist presence in the national politics and a powerful Madrassa lobby in the academic arena, Moniruzzaman Commission took a position of appeasement. The Commission proposed a number of retrograde steps, such as gender segregation in co-educational madrassa, separate cadre service for the Madrassa graduates, granting equivalence to the Quomi madrassa degrees etc. The present government had set up a committee in 2009 to chalk out an Education Policy for the country. Their recommendations have now been enacted as the Education Policy 2010. The Policy proposed a number of reform measures, including some in the madrassa sector. Some of the important recommendations are:

Restructure Ibtidaia education to bring it in conformity with the 8-year uniform primary education.

Put greater emphasis on Bangla, English, Mathematics, Social Sciences and environment.

Introduce IT and vocational courses starting from sixth grade, so that those who drop out after primary stage can pursue vocational training and career later on.

Restructure 2-year Dakhil (Secondary) and 2-year Kamil (Higher Secondary) courses to prepare the students to pursue higher education in different streams.

Establish Madrassa Teachers Training College. Bring the madrassa teachers' pay scale in line with those of the mainstream schools.

Set up a separate Quomi Madrassa Education Commission that, after consultation with all strata of the society, including the teachers and students of the Quomi Madrassa, will suggest how best to improve the syllabus, course content, text books, quality and facilities in those madrassas.

Introduce registration, inspection and accountability of all madrassas, in line with other educational institutions in the country.

The Commission's recommendations were hailed as a bold step forward by the civil society. However, those from the Quomi Madrassa lobby vehemently oppose its implementation. Their main objection stems from the fact that the Act aims to bring the Quomi madrassas under some form of govt. control and supervision. The Governing bodies are afraid of losing their autonomy and the teachers are afraid of losing their jobs for not meeting the education minima. The madrassa students who are to gain the most are powerless in the face of the Governing Bodies and the teachers. There is an information gap between government and the people that the vested interest group attempts to exploit. That the Madrassa students are the ones to gain the most from the reform measures needs to be advocated vigorously by the government.

A study of the genesis of madrassas reveals that ours represent a fossilized version of a great Islamic tradition. The two streams of Madrassas in the country are but a legacy of our colonial history; it is neither modern not Islamic. Multiple streams of education in our country reflect the economic and opportunity divide, an undesirable situation in our nation-building efforts. If we want to see a modern progressive Bangladesh to emerge, we need to have educated youths able to meet the challenges of the 21st century. While we would definitely like to have our young people proud of our religious and cultural traditions, we would like them to be equipped with the latest tools of science and technology. As our resource is limited, we need to ensure its optimum use. The need to reform Madrassa education, especially the Quomi stream, is long overdue.

The writer is Registrar, BRAC University, Dhaka.