Parliamentary debates: A quality assessment

Syed Manzoorul Islam

|

Photo: Sazzad Ibne Sayed |

There is such a thing called parliamentary language which is best defined by the discursive practices in parliaments where informed and well-intentioned law makers, respectful of democratic norms, battle it out with political adversaries on issues that concern the local electorate as well as the interest of the nation. The language they use is straightforward since substance is what they are after, not show, although show, which translates ideally as style, has its place too but is often laced with irony and innuendos, and a generous dose of wit. Parliamentary language is a Wittgensteinian language game, where both parties know the rules but continuously stretch them to come up with newer connotations and meanings. The important thing however, is that both parties agree on the new meanings and wordplays. In the British House of Commons, members may not use certain words considered impolite or too attacking, although that doesn't stop them from using sugar coated euphemisms. The bottom line in parliamentary debates in advanced democracies is: no vulgarity, no unseemly and unjustifiable verbal attacks and no hitting below the belt. The speaker expunges any word or expression he considers unparliamentary, and may admonish the member for using them.

Some years ago Bangladesh Television regularly aired a weekly English parliamentary debate for school students for a quarter each year where young debaters practised their best manners and impressed everyone with their sharp-witted and substantial arguments for or against wide ranging issues. I used to moderate the debates as 'the Speaker.' Before each debate I reminded the debaters to strictly follow the language norms. Once a debater called another 'mad,' and I moved to expunge the word. The debater quickly came up with a substitute: 'What the honourable member is saying, Mr. Speaker,' he said, 'would prick the professional interest of a psychiatrist.' He was greeted by a roar of laughter from the house. The member in question objected, but I found nothing objectionable. The debater had scored his point without having to resort to swearwords or invectives. Later, the debater told me he had heard worse language in actual debates in our parliament. Someone called someone pagol chhagol, he told me, but the Speaker neither expunged the word nor allowed the irate member to raise a point of privilege. To this day therefore, in the parliamentary proceedings at least, the honourable member remains a pagol-chhagol!

Parliamentary debates, ideally, should be broadbased and of consistently high quality. An issue should be examined from all possible angles, by supporters as well as detractors, before the house takes a decision. A parliament is a place where laws are enacted, where the budget is placed and debated, where members discuss local problems or policy formulations: a parliament, in other words, is a place where the country's intellectual capabilities are tested and its negotiation skills are demonstrated; it is a place where language games are played to outwit opponents and score high marks not for the sake of personal aggrandizement, but for the good of the nation. A parliamentary debate should be a riveting exercise, where facts are piled on facts, and arguments clash with arguments, all in a language that is charged with emotion and passion, yet allowing for the play of plenty of wit and humour. The debaters agree to disagree, or disagree to agree, but the debate is all about issues, not individuals. A parliament where members throw invectives, menacing glances, files and shoes, among other things, at each other is a poor parliament indeed, since it fails to function by consensus; but more than that it shows the mental poverty of its members who cannot argue a point like grown up adults.

If at this point someone tells me that this is also what pretty much happens inside our parliament, I'll have to disagree. Our parliament, for most part, is a peaceful place since it only hears government party MPs. The other day I saw on CNN news how members of parliament of a far eastern country were violently fighting with each other. Not with words, but with fists. I found the brief footage sad and amusing at the same time since I saw two guys getting pummeled and then some, but no one was actually saying anything all that they were doing was shouting and fighting. I am sure the fighting came after a long spell of an intractable debate, or may be, because of it. And I am also sure they talked sense through most part of the debate. The important thing to mention here is that both the government and opposition sides were there under one roof. Sadly, this hardly happens in our country. A debate necessarily implies the participation of two parties. In our parliament there is only the government party the opposition finds it more worthwhile to practice its democratic rights on the Rajpath streets, thoroughfares. For the last twenty years or so, ever since democracy made a much vaunted comeback, the opposition considers it below its dignity to sit in the house for long spells. Or may be, given the nature of the Rajpath activism, sitting for long spells in parliament is a contradiction in terms. The government too, considers the presence of the opposition in the parliament a pain in the neck, an unnecessary intrusion on their privacy. It devises ingenious ways to ensure their absence ranging from denying the opposition one or two front row seats, to turning their microphones off when (or if) they find an occasion to speak. In the absence of the opposition, there is thus no debate, but longwinded speeches, short outbursts, well rehearsed eulogies, extemporized paeans (depending on how important or unimportant the member is in the eyes of the Speaker) all in raise of the Prime Minister. We actually have a session for thanking the president for his speech at the opening of a new session of the Parliamnet. The session turns out to be interminably long, and often, towards the end, borders on the bizarre and the absurd. For several weeks, members thank him for all sorts of others things from giving the nation 'crucial guidelines' to 'rescuing the constitution' to 'saving the nation in a time of crisis.' Copious praises are also heaped on the Prime Minister for the same reasons. The opposition can speak on the President's speech, but they first have to be there to do so. Once or twice in our parliamentary history, the opposition did speak, and naturally the opposition found the same speech by the President 'ill-conceived,' 'travesty of truth,' and 'aimed at pleasing his and his party's mentors.' I am sure everyone by now knows who the mentors of Awami League or BNP are! They don't need to be mentioned by name. If someone however doesn't still have a clue, he or she should seriously consider leaving the country.

Bangladesh Television broadcasts the parliamentary proceedings live, with the pious intention of bringing the workings inside the parliament to the knowledge of the countrymen. If people have voted their men (and women) to the parliament, believes BTV, they have every right to listen to what they say in the house and also see what they do. For the last twenty years, that right of course has belonged to voters electing the government party MPs those electing the opposition MPs have been hard-pressed to seek their MPs out on Rajpath if they needed to know what they were saying or doing. What the MPs sometimes say, of course, is unsayable and on this score the less we say is better. What they do is much less harmful though, like having a shut eye or reading the day's newspaper, or chatting with colleagues. But that's beside the point. I have seen pictures of MPs in European parliaments sleeping in rows. Happens everywhere.

|

Photo: Amirul Rajiv |

What is really upsetting is the quality of language some of our MPs use. I am a great lover of local dialects I myself speak one whenever I can. But I am totally opposed to banalization of Bangla by way of punctuating it with unnecessary English words, by distorting the standard pronunciation and by killing its natural grace by using a strain of 'metropolitan Bangla' which springs from the assumption that all urban people should speak the same distorted lingo. Many MPs speak in fragments, and lose their track halfway through a 'speech.' What usually should take two minutes to make perfect sense of, may take twenty minutes to finish. In other words, the language used in the house makes us wonder why in such an august body as the parliament not everyone is respectful of our mother language and the sensibility of the listeners.

2. The parliament cannot have a proper debate in the absence of an impartial and unbiased Speaker. Unfortunately we cannot say that all our Speakers have met our expectations in this regard. The Speaker's seat is literary placed at a higher elevation than that of the members including the Prime Minister's. Symbolically, this elevation implies the Speaker's exalted position. He has to act like the parent of disputing children: he cannot show any bias towards anyone, and has to be patient, wise and quick witted. The Speaker, also have to have a good sense of humour, since laughter, emanating from the Chair, can cool inflamed nerves.

The Speakers in our parliament, with a few exceptions, have been sincere about their duties, and have indeed reached out to the opposition on many occasions. But the government party does not at all like such a position of the Speaker. It routinely monitors him, chastises him and forces him to be more pro-government. Our Speakers routinely ignore opposition member's queries. Even on the Prime Minister's question and answer day, opposition members are not allowed to ask her any questions. The government MPs steal the show, and their questions are designed more to praise her and win her approval than for soliciting answers. A month ago MPs had a ninety minute unscheduled discussion on the Prime Minister's receiving an honorary doctorate from St. Petersburg University. One MP even proposed that she be given the Nobel Prize. The Prime Minister, mercifully, was was not in the house.

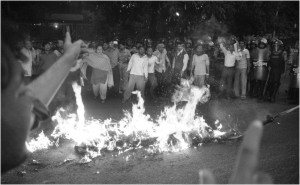

3. We however, cannot presume that the parliament will forever remain a one party house, which does not allow any debates but only conducts routine business. We must believe that the opposition will go back to the Parliament, and discuss issues and policies that concern the people and the country. The opposition should realize that Rajpath is an old, hackneyed concept: it is destructive and counterproductive, and only leads to violence, bloodshed, incarceration and public inconvenience. We can tolerate an occasional Rajpath, but the bulk of the opposition's activism should be within the parliament. Once the opposition sits in the house, even one seat less in the front row, and starts constructively opposing, challenging and engaging the government, it will revive the tradition of good old parliamentary debate.

When that happens, both the quantity and quality will improve. In place of unnecessary praise and hurling of abuses, the house will see more constructive exchange of views more often. Increase of quantity doesn't mean longer debates, but more frequent debates with a purpose. If members begin to go after facts, and argue like the best debaters I have seen in my younger days (some of them were MPs, some still are MPs). I am sure the quality will come up.

For quality debates one needs four things: a thorough understanding of the subject of the debate; an excellent command of language; an inimitable style that demands respect from the opposition and a sense of humour. Many of our MPs do possess these qualities, but in the absence of a competitive and democratic environment, they do not have any opportunity to either show them or develop them further. What is worse -- even good debaters slip into inane monologues full of self praise and praise of their leader. Young lawmakers thus miss the opportunity to hone their skills.

Let us hope that the next session of the parliament resumes its full function. I am sure the government will see how important the presence of the opposition is in the parliament for the good of the nation, and the opposition will see how the Rajpath logic is outdated and unsuitable for a forward looking country like ours. The sooner they start doing so, the better.

The writer is Professor, Department of English, University of Dhaka.