Constitution on a rollercoaster

Professor M Rafiqul Islam

|

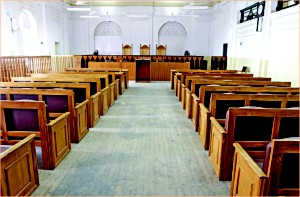

Photo: Star |

THE original Constitution: The quest for constitutional and democratic governance culminated into a war of liberation out of which Bangladesh was born in 1971. The Constitution was finalised, authenticated, and implemented in December 1972. It contained nearly every aspect of a good and responsible government in parliamentary democracy with the separation of power and checks and balances between the government organs. It introduced collective and individual ministerial responsibility to Parliament and ultimately to the people, constitutional supremacy (Art. 7), judicial independence, a populist political and liberal economic system, transparency in public policy formulation, and administrative accountability. It recognised human rights, fundamental freedoms, and rule of law for all with appropriate judicial scrutiny and enforcement (Arts. 44 and 102). However, this is not to assert that the Constitution was perfect. What is highlighted here is that, on balance, this Constitution was by far the best one could reasonably hope for under the Westminster model. Subsequently, successive uses of the Constitution as a political tool through multiple amendments diluted its integrity and eroded certain crucial features of good governance.

Major amendments: Some major amendments to insulate selfish power politics and unlawful acts caused extraordinary crisis and political impasses with far reaching debilitating consequences on the development of a constitutional order. The Fourth Amendment altered the form of government from parliamentary to presidential in 1975 with an all-powerful President to be elected directly by the people. It reduced the power of Parliament and the apex judiciary and established a single-party state under the National Party (Part VIA). The concentration of executive, legislative, and judicial powers in the President undermined the constitutional safeguards of separation of power and checks and balances the cornerstone of the 1972 Constitution.

The Fifth (1979) and Seventh Amendment (1986) validated two martial law regimes by pliable parliaments. Why were these validations necessary? If the regimes were valid in the first place, there was no need for such validation. These validations presuppose that the regimes were invalid. If they were inherently invalid, how could they be validated retrospectively? The Constitution contains no provision for martial law and/or its validation on any ground and under any circumstances. The change in government must take place pursuant to the constitutional procedure in Part IV. The omission of martial law is not incidental, but intentional, based on the historic experience of Pakistan where democratic governance and constitutional order was frequently frustrated by ambitious and politicised army takeovers. Both Zia and Ershad were well aware of their unconstitutional access to power and wanted to avert any Asma Jilani type decision, which declared the martial law regime of Yahya illegal in 1972. They surmised that their actions could be nullified and declared illegal by any court of law with potential prosecution consequences. Through these amendments, both Generals sought impunity under the same Constitution which they arrogantly ignored in accessing to power. They illegally derived their authority from martial law that they themselves created parallel with, and repugnant to, the Constitution. It is legally self-contradictory and inconceivable to maintain that they could derive their authority from martial law and justify their actions under the Constitution, which outlaws the former. They sought to legalise by ballot their martial law regimes that they imposed illegally by bullet. The recent Supreme Court decisions on their profound lack of legal and constitutional validity were long overdue and a foregone conclusion (my article: Political Quarterly, London, 1987, pp. 312-331).

The Eighth Amendment, 1988 accorded 'Islam' the status of state religion after Zia dropped in 1977 secularism as a fundamental principle of state policy in Article 8 of the Constitution. This Amendment seemingly placed minorities in a different, if not discriminatory, position compared to the majority Muslim in respect of religious rights and constitutional guarantees under Articles 27, 28, and 29. The contents of these Articles are not merely declaratory but entail substantive legal force, as they are adopted from the western secular and non-communal tradition which may be difficult to subsume within the value system of any given religion. The unqualified endorsement of secularism in the 1972 Constitution was not superimposed by outside powers; nor was it a coincidence. It has a powerful sentimental attachment to and deep roots in the glorious genesis of Bangladesh. The vivid memory of communal riots in 1947 and the abuses of religion for sectarian politics and economic ends in Pakistan drifted the Bengalees to secularism as an alternative. This commitment to non-communalism reflected beyond doubt in all pre-independence movements, the 1970 elections, and the 1971 liberation war. Many Bengalees sacrificed their precious lives to passionately cherish a value-oriented lofty ideal that we and our future generations would live in a true non-communal environment. This Amendment was a blatant insult to the fundamental ideals inseparably linked to the soil of Bangladesh and the blood of its people. Yet this substitution was accomplished by two Generals without any popular mandate or referendum required to amend Article 8 (Art. 142).

|

Photo: Star |

The Thirteenth Amendment 1996 introduced a non-political caretaker government to conduct free and fair elections. It temporarily transforms Bangladesh from the parliamentary to presidential form, conferring some real and absolute powers, including full control over the defence forces, on an appointed and ceremonial President, who is not entitled to these powers under our parliamentary government. The Chief Adviser and ten Advisors of the caretaker government are the appointees of, and responsible to, the President, who, being unelected, is not accountable to the people. Turning a figurehead into an all-powerful president effectively introduces an interim presidential form of government during the tenure of the caretaker government, which is evidently inconsistent with the basic structure of the Constitution. The exercise of this unfettered and unaccountable power precipitated constitutional crises in the past, exemplified by the unilateral and arbitrary sacking of the Army Chief in 1996 and the continuation of the caretaker government in 2007-8 without holding elections within the stipulated 3-month timeframe. Holding free and fair elections is intuitively appealing to restore public confidence in election results. But the means of holding credible elections does not necessarily have to be contrary to, but can be based on respect for, the constitutional spirit and basic structure. This amendment has sought to achieve a desired end through unconstitutional means. As long as the political party in power is entitled to nominate and appoint the President, the caretaker government is anything but non-political and neutral.

Current pressing constitutional issues: The incumbent government wants to bring back the 1972 Constitution without secularism but with the state religion. Two suns cannot rise on the same sky. The 1972 Constitution cannot be resuscitated with its full integrity and coherence within the context of a single religion in religiously plural Bangladesh. The government was presumably looking for a simplistic solution to a complex problem, which may well militate against the constitutional rule of law. It has the potential of influencing the enactment and interpretation of laws repugnant to a number of international human rights instruments of which Bangladesh is a party. The Supreme Court's advice to retain the national identity as 'Bangladeshi' as opposed to 'Bengalee' or 'Bangalee' is appropriate and consistent with worldwide practice. The nationality of a citizen is associated with the statehood in international law and not with his/her ethnicity or race.

The ongoing trials of international crimes against humanity/war crimes, launched pursuant the International Crimes Tribunal Act 1973 have given rise to concerns expressed and calls made relating to the compliance with the so-called international standards.

The issue has dual aspects: substantive law of the designated crimes and procedures to be followed to conduct the trial. The crimes before the Tribunal are recognised crimes at international law long before the enactment of the Constitution and the 1973 Act, which is merely a catalyst to try those specified crimes committed in 1971, predating these two documents. The argument that the application of the 1973 Act to crimes committed in 1971 is retrospective, prohibited by Article 35 of the Constitution is erroneous. These crimes and their prohibiting international law existed at the time of the commission of those crimes in 1971. The Tribunal would interpret and apply well developed international criminal law and judicial precedents to try these crimes. Procedurally, there is no common, but minimum, international standards to be followed in procuring and presenting evidence. Every war crimes trial is unique, warranting tailored, not one type fits all, procedural standards. It is an evolving process. Operating since 1993-94, the Bosnian and Rwandan Tribunals have been developing and improving their trial procedures. Nothing prevents Bangladesh War Crimes Tribunal to follow these precedents to develop its own procedural standard as the need arises in the course of conducting the trials. Procedural standards are important means of fair trials but they should not be stretched to frustrate the very end of the obligation to end the impunity of the perpetrators of the heinous crimes of 1971.

Observations: The forty years history of the Constitution is littered with instances of its exploitation as a political ploy to camouflage illegal sectarian political supremacy. This process not only hamstrung its dignity, but also stultified the natural development of good governance and a political process ensuring orderly change in government and yielding political leaderships and institutions. This deprivation is yet to be dissipated. Law-making may be improved by educating and training of parliamentarians about the constitutional role and limitations of Parliament and its standing committees. The judicial review power of the Supreme Court must be appreciated and strengthened to scrutinise the constitutional validity of any doubtful parliamentary or executive act. The introduction of a televised 'question-answer' session particularly for the Prime Minister and the broadcasting of parliamentary proceedings may ensure legislative transparency and accountability. To augment its stature, a parliamentary secretariat independent of the public service, appropriate disincentive/penalty for absence/boycott of sessions, and a bi-cameral non-political upper house as a check to keep Parliament within the bounds of the Constitution may not be gainsaid.

A balanced judiciary must be independent and accountable in exercising its judicial power rationally and justly. The Constitution provides no specific provision for judicial accountability to the people. Being appointed, not elected, does not mean that judges are not accountable to the people, whom all power of the Republic is vested. Constructive public criticisms of the Judiciary benefit judges to be more careful, rational, and fair in decision-making. Judicial independence and public accountability are mutually complementary. The former endures if the latter strengthens. The myth of judicial isolation, immunity, and contempt of court proceedings to insulate from public scrutiny are now being replaced by conscious public outreaching efforts by modern and responsive judiciary. The form of government has changed in 1991 but the legacy of the invasive executive seemingly continues unabated in parliamentary government. The Executive is not superior or stronger than the legislature and judiciary. Constitutionally, the Executive is subject to political control by Parliament and legal control by the Judiciary. Adherence to the constitutional rule of law and due process in performing executive functions is a pre-requisite for good governance. The challenge ahead is to render the vast empires of executive actions amenable to constitutional order. Otherwise, the prospect of a responsible good government is likely to remain as elusive as it has been over the past forty years.

The writer is a Professor of Law, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.