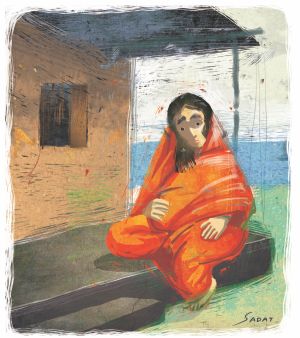

Fiction

She

Syed Manzoorul Islam

|

Four years into her marriage, Lipi has her first real chance of becoming a mother. It is the village midwife Renubala who gave her the news, about a week ago, reminding her that motherhood at her age doesn't come easy. At her age? Well, let's not guess Lipi's age it's not decent. Anyway, she couldn't be more than twenty three. What should rather concern us is the sudden pall of gloom that has descended on her. The news should have made her ecstatic; indeed, she should have been over the moon by now. Why, then, has she become so worried? Well, it is because her husband Gafur has told her that the child better be a boy. If it's a girl, he wouldn't be able to support Lipi any more. Gafur, a construction worker, had gone to the Middle East some years ago to try his luck. He had somehow landed a job in a desert strip that paid him well but didn't allow him to visit home more than once a year, and that too, for a mere three weeks. On each of his last three visits, he has tried as hard as he could to give Lipi the gift of motherhood. 'What is a married woman without a child,' he has told her, echoing his beloved mother, and his not-so-beloved father. But that gift has somehow eluded Lipi until this auspicious spring. Gafur's grandson-craving parents had of course come to believe that it was their son who was not ready to be a father not yet. 'Why bring a child whose father would be nothing but an absence in his life?' he had told his parents, shielding Lipi from any accusation of barrenness. This time around he has not come home on a furlough but has been sent packing by his employers forced to downsize their operation because of the global economic meltdown. Gafur is without a job now and will be staying home for at least a year. So when Renubala broke the news that he was going to be a father, he told Lipi, 'I have kept my part of the bargain. Now it's all up to you.' Meaning, I gave you a child, now you must see to it that it's a son. If you can't, well, I can't guarantee what will happen next.

Lipi agreed. She knew all too well. Ever since his son's marriage, Dulal Mia, has been obsessed with the thought of becoming a grandfather. 'All I want is a boy who will carry the torch of my family,' he has told Gafur over and over again. He somehow has never talked to Lipi. He hates her pretty face, her long hair and her shiny cheeks. He suspects her to be a 'fallen woman,' the kind who runs away with the first man who happens to come along when the in-laws aren't watching. He also holds Lipi responsible for sending Gafur away from home, conveniently forgetting the fact that Gafur had been working in the desert strip well before Dulal Mia was sorting out potential brides for his son. When Gafur is away in the Arab desert, which is most of the year, Dulal Mia takes it on himself to keep an eye on Lipi the whole day, and a good part of the night as well, and particularly in the small hours when Lipi goes out to respond to the call of nature. He has forbidden her to go to the tattu the loo, the bamboo fenced toilet that borders the family's backyard without first waking him up. While Lipi is inside the tattu, Dulal Mia stands guard a little distance away with a four battery torch in hand. The tattu at night is nothing but the devil's brothel bed he has learned from his revered father. Lipi finds her visits to the tattu a real battle, on top of the umpteen numbers of battles she has to fight every day.

What are these battles, you ask? Don't. We can't talk about them even with a fraction of the patience with which she has been fighting them. Our apologies.

Dulal Mia has partially retreated from view after Gafur's untimely return. But the nature of Gafur's return has created some additional problems. Coming back home with a pink slip is not the same thing as coming back on a sweet home leave. Dulal Mia has made the distinction quite clear. If Lipi gives birth to a daughter, he has told Gafur in no uncertain terms, mother and daughter would have to find food somewhere else. His booming voice was loud enough for Lipi to hear even if she were washing pots and pans in the pond, some distance away. Gafur sighed. 'Give me a son, Lipi darling,' he has pleaded with his wife.

Lipi took Gafur's hand into hers, and placed it on her swollen tummy. Her child was moving restlessly under her skin, giving her a fright. What is this child doing? She wanted to know. Why is he kicking so, as if he wants to split my side and jump out into the world, much before his time? As if he were a tiny dinosaur, bursting out of an egg, determined to spread terror across the world?

The comparison with a dinosaur is of course, not Lipi's: it's ours. How can a village woman, who had only seen the inside of a school building once or twice, know about dinosaurs?

Gafur placed a gentle palm on Lipi's tummy. Wow! Smooth and cool as a watermelon. But whoa! What was that? God, that really hurt! Hadn't it been a full blown kick that had almost broke his fingers?

Gafur was ecstatic. 'My dear Lipi,' he moaned, muttered, and then screamed. 'It's boy. Who else but a boy kicks with such power? It's most certainly a boy.'

Gafur's ecstasy smoothed all the wrinkles of worry on Lipi's forehead. 'O Allah,' she exclaimed, lifting her head heavenwards, 'you've heard my prayers.' For a moment, she thought she could see the face of the child. A smaller, but much cuter version of Gafur, with no resemblance to that monster Dulal Mia.

Gafur, meanwhile, gave a huge shout of joy and began jumping up and down. The noise drew Dulal Mia to the scene. 'What's up, my son?' he asked, directing his beady eyes at Lipi.

'A boy,' Gafur said, his voice almost choked by emotion.

Dulal stole a glance at the exposed belly of Lipi which he thought was of the shape of Pradip Dhali's drum only much smoother. On an impulse he placed a hand on her belly, which Lipi had forgotten to cover up, having been carried away by Gafur's delight. She felt Dulal Mia's cold and dirty hand clutching the taut skin of her belly. Her eyes darkened and she felt like throwing up. Suddenly, Dulal Mia screamed, as if he had seen a ghost.

'What's the matter, Dad?' Gafur exclaimed. 'My hand, my hand, its broken. The bastard has shattered my old bones,' the old man shouted in pain.

The bastard in Lipi's womb didn't like the ugly, groping hand feeling for it. It threw the kick of a lifetime, with the result that Dulal Mia was left writhing in pain. His old bones, of course, were brittle, not hardy like those of his construction worker son.

Dulal Mia's scream brought his wife, Lutfa Begum to the scene. You haven't met Lutfa Begum, have you? Never mind. It's our fault. But you haven't missed much, we guarantee. You've seen hundreds of Lutfa Begums on the telly, thanks to Sony and Ztv channels. You may even have a few of them amongst you, for all we know. The kind of mothers-in-law whose sole pleasure in life lies in torturing poor daughters-in-law to death, grinding them slowly and surely until nothing is left of them but a pile of pulverized mess.

Lipi had by then covered her belly, although the need to throw up remained strong. She was trying to get up and head for the pond when Lutfa Begum put her hand on her throbbing belly and shouted, 'Who told you this is a boy? This is a girl, I tell you. A slut like her is incapable of bearing a boy.'

The boy or girl, whoever it was that had assumed the role of a kick boxer inside Lipi's womb, now sent another kick, this time at the wrist joint of Lutfa Begum's left hand. The impact nearly broke her old bone. A construction worker's mom doesn't necessarily have strong bones!

Lutfa Begum used her left hand to touch Lipi's belly as she never uses her right hand for unclean purposes. Now she regretted her mistake. Her left wrist had once dislocated felling from a tree when she was a girl. It had taken a long time to heal. Now the unborn monster in the slut's womb had snapped it along the old crack line. Lutfa Begum left the room holding her hand, screaming.

Lipi couldn't believe what was happening. What was it that sent both of her tormentors packing? A knight in shining armour? What a feat! She clutched her sari and sank into the bed, feeling all the happiness of a few minutes ago returning, redoubled. She lay on the bed, breathing easily, happily and alone, after what seemed like an eternity. The little thing inside her had got rid of the two sentinels that guarded her day and night, not allowing her a moment alone with herself.

She placed a hand on her tummy and cooed softly, 'My little thing, my son, my knight in shining armour. How does your mummy love you!'

Her voice was soft and mellow, scarcely rising above the sound of bamboo leaves brushing against the window as a gust of wind played with them.

2. The unfortunate kick that cracked Lutfa Begum's bone drove her crazy. She was furious at the unborn monster the slut was carrying. She had a gut feeling that the child was a boy no girl could throw a kick that strong. She knew it only too well. Hadn't she herself been kicked around when she was young, by just about everyone she could remember? Could she ever, ever kick back? Could she so much as raise a finger at her tormentors? Now, after all these years, during which she had steadied life's ship, piloting it confidently, this scheming villain had appeared, a whorehouse reject, bent on complicating her life, and intent on bringing a brat in to the world. The brat that nearly broke her wrist has reminded her that she has to find someone else other than Lipi to kick around.

A few more months! She knew how it would go. The village midwife Renubala would dig the screaming and writhing monster out of the slut's womb, wrap it in a piece of kantha and bring it right to her. 'It's a grandson, Lutfa Apa,' she'd say, 'Ask someone to call out the ajan.' Why, Lutfa Begum could even visualize Gafur jumping into the yard, singing out a comforting ajan in praise of Allah and His Prophet, his voice trembling with gratitude. That moment, alas, would also bring an end to her lording over Lipi. That is why Lutfa Begum kept repeating in a shrill voice, 'I tell you it's a girl. No bazaar woman could give birth to a son. Not certainly her. Shouldn't we kick them out now, when there is still time? What? Na? I say throw them out if you want to be saved.' Lutfa Begum sounded like that old siren Dulal Mia used to blow when cyclones threatened to level the coast. That was a long time back when he worked as a Red Cross volunteer. Lutfa Begum somehow had the same wail, the same nagging insistence. Dulal Mia too had been hurt, although his pain was beginning to lessen. But he felt in his heart that the child was a boy. He certainly wouldn't do what Lutfa Begum wanted him to. He would be more than happy to throw the slut out, but not the male child. He would rather wait till the baby and the bathwater were separated!

Gafur, for his part, smiled. He knew his mother, and knew how her bellowing voice would grow shriller and shriller before she choked. She would then be forced to fall silent, although her eyes and her face would continue to show her anger and disgust. Gafur's smile, so out of place in the aftermath of Lutfa Begum's angry outburst, would have been enough for either of his parents to jump on him, especially since he was without a job. But he was saved by the little money he had set aside in a bank for the parents' upkeep, which only he could encash. Gafur, like his father, was also convinced that he would have a son. He had genuinely warmed to Lipi, buying her small gifts mostly delicacies like fruits and chocolates but on the sly, fearing his parents' displeasure. But Lutfa Begum's hawk eyes duly registered Gafur's small indulgences, fuelling her wrath. And as Gafur warmed up to Lipi, Lutfa Begum began to find newer and newer chores for her. Suddenly the milk cow needed to be bathed and the yard swept twice a day. Or a sari she had worn just once needed to be washed again. Who else but Lipi to do the chores, since Lutfa Begum's wrist would take ages to heal, if at all? Let the slut work herself to death, Lutfa Begum thought, with undisguised glee. One never knows a sudden pain in the underbelly, a sudden spasm stabbing the heart, and the child would be flushed out like a lump of stale flesh. If that happened, she swore, she wouldn't be heartbroken.

The slut was assuming airs with each passing day. She was obviously puffed up by all the attention Gafur has been showering on her, and by the prospect of being the mother of a son. But Lutfa Begum knew how to cut her down to size. Give her more work. Difficult work. Backbreaking work she told herself. That way lies freedom!

3. Lipi has a problem and a really big one at that. She can't stand up against anyone, no matter how serious the hurt they inflict on her. Lutfa Begum is constantly at her back, taking her to task for offences real or imagined mostly imagined. All she does when the two in-laws descend on her is run away to the pond, and sit on the ghat shedding tears. Even Gafur is exasperated by Lipi's submissive nature. 'Don't come crying to me. Fight fire with fire, if you can,' he shouts. Lipi, for her part, prefers to play dead. When the going gets tough, she has the pond to herself. But at night or when a storm blows, the pond becomes an impossible destination and Lutfa Begum lands a few whacks on Lipi's back with a greased cane. Dulal Mia of course avoids the cane. He likes to lay his hand on her, on parts of her body that she guards so vigilantly from his eyes. After Gafur's return, the beating has stopped, but not the verbal abuse. And now, after Lutfa Begum's wrist bone snapped, Lipi is hearing the unspeakable words more than ever, as her daily chores take on back-breaking proportions.

Lutfa Begum had never gone to school, but no one can say that she has no intelligence. Quite the contrary. Dulal Mia believes she can match any village politican in intelligence or in cunning, which is all the same for him. One day she fell in the yard while crossing over to tend how her milk cow. The fall was mild she broke nothing, but when she rose to her feet with much effort, she let out a scream. 'O my poor leg,' she cried, 'first my hand, and now my leg.' She wobbled and was about to fall again, but Lipi was nearby, ready to lend a hand. The old woman put all her weight on Lipi, and demanded to be carried to her bed. Lipi had no way of saying no. And against Renubala's strict orders, she lifted the old hag on her shoulders and headed for her bed.

If you saw Lipi at the task, I am sure you'd take pity on her. For our part though, we just looked away. We are not known as unkind storytellers for nothing.

So Lipi's chores mounted. She was nothing more than a household donkey now. Why, wasn't she big with a child? You might ask. But didn't Lutfa Begum herself, or her mother before her, do the same may be much more when they were big with child? While being transported to her room after the fall, Lutfa Begum was hoping that her weight was good enough to snap the girl. But it didn't happen some saint must have felt pity for her. Angry, Lutfa Begum began to curse her. 'The monster you are carrying inside you, that little bitch, she will be your undoing, I tell you.'

How?

'That bitch will run away with the first village idiot that comes her way, you'll see. And then who will save you?'

But will you, rotting old hag that you are, survive till then?

'Are you talking to me? Do you dare to open your mouth?'

Silence. Which often comes at the price of gold. Ask Lipi how much she pays for a moment of silence.

4. Gafur is of little help when his parents are around, which is most of the time. His father used to run a restaurant in a small town nearby. But a fire gutted down the restaurant, and badly burnt one of his legs. Ever since he has been forced to stay home. But once or twice a month he shuffles to the village bazaar where he owns two shops, to collect the rent or do minor repairs. The shops bring him good money, so Dulal Mia is not keen to find work again. With Lutfa confined to her bed, he has renewed his watch on Lipi. For the poor girl life is simply becoming unbearable. Her day begins before sunrise, and ends well after Dulal Mia finishes his supper.

The burden has become too much for Lipi. 'When will this end?' she asks. 'When will I find release from all the labour, my son?' she now addresses her unborn child. 'I can't stand it, my son. Why don't you come and rescue me from this pit, like the knights in shining armours I read about in books? Any answer, my prince?'

Her prince starts moving. She can feel his small limbs thrash against her womb, as if he is putting on his mail coat, and unsheathing his sword. He holds her tummy and she lies down on the bamboo mat on the verandah. And falls asleep.

5. It's a pretty evening, like the ones she had seen in picture books all those years ago. Full of softness and the scent of unseen flowers. And the rustle of birds returning home.

Lutfa Begum is sitting on her prayer mat, head bowed. Dulal Mia had dragged himself to the mosque. Gafur had gone to the bazaar, and was having a good time with friends.

Lipi is sleeping on the mat. Darkness has descended on her like a soft quilt, but so have the mosquitoes. Their drone answers the dying notes of the departing cicada. A champa has bloomed somewhere in the throng of trees near the pond, spreading its unworldly scent. A night bird is announcing its arrival, cooing a few notes. Not the usual sad ones it was singing even two days back. The bird's notes are upbeat, as if the night is going to be a special one. Or, is the bird trying to wake up Lipi, as it senses something?

Don't ask. We are no bird specialists. We don't even know if birds feel for pregnant mothers. That's something the famous ornithologist Sharif Khan might be able to tell you.

A plump moon, emerging from the depth of the sky, is floating in liquid light, and has anchored itself above Lipi's little yard. The moon shines whitish bright, as if washed in dew. It has lit up the tin-roofed cottage, the clutch of trees near the pond, the pond itself, and the puin clump over a bamboo scaffolding. A bird has arrived to awaken Lipi. She opens her eyes. She has one hand on her belly. The hand trembles. No, Lipi is not having a crying fit. Her hand shakes because something or somebody has given it a push. Lipi knows: it is her little prince. She feels a tiny hand groping for her sari-end. Then another hand. And then a small body lifts itself out of her womb. The little figure that emerges takes a few moments to balance itself. Then it jumps on to the mat, positioning itself near Lipi's folded knees. Then it somersaults. And before Lipi's wonder-filled eyes can figure out what is happening, the little one is on the yard. A few paces of wobbly walk. Then it stands erect, and stamps its feet on the hard clay soil of the yard, just as a horse does, before taking off.

As Lipi keeps gazing in disbelief, the little one begins to grow taller. First the height of Lipi's thighs, then her breasts, then her shoulder, finally standing towering over her, taller than she ever has been, even with the high-heeled shoes Gafur bought for her after their marriage. Lipi lies supine on the mat, her eyes catching the trembling of a red anchal, and the fluttering of a red-bordered sari above the little one's ankles. Lipi's eyes travel upward along the folds of the sari to the little one's little woman's, she corrects herself tummy, just where her belly button sits like a crown jewel. Then to a red blouse and two small, firm breasts over which she has draped her sari. And then to a smallish face, fresh, self-possessed . . . and beautiful, flushed with an intense smile. The little woman has a matching red teep on her forehead, but her straight, silky hair dances wildly in the wind, which she tries to bring under control with her hand. Lipi sees with amazement how the fingers shine in the dark, like fine champa blossoms. A fairy, certainly, Lipi thinks, a pari from the story books of her childhood. The pari gestures towards her to keep lying down, tucking her sari end around her slender waist. Then she gets down to work. First she picks up the jharu and sweeps the yard clean. Then she enters the kitchen. A minute later she emerges with two pitchers and heads for the tubewell.

Lipi closes her eyes. No. One shouldn't dream such a dream. It's painful, she says. Her dream is telling her that all these chores await her this sweeping of the yard, and collecting drinking water. She decides to end her dream, but hears the pari calling her. 'Ma, don't get up. I've done everythings there is to be done. Catch some sleep now, while you can. I've lighted some dhuna incense in a bowl the smoke will keep the mosquitoes away.'

6. The pungent sweet smell of dhuna tickles Lutfa Begum's nostrils. She shouts, 'Who told you to waste my dhuna on yourself, bitch?'

Dhuna? What is she saying? Lipi thinks. But she too smells it, and sees the whiffs of smoke rising from the dhuna bowl. The mosquitoes too seem to have departed. God, what now? How can I explain myself? She gets up, extinguishes the dhuna, and enters Lutfa Begum's room. But Lutfa Begum's attention has been diverted to something else to her neatly folded saris on the clothes horse, to the cleanly swept floor which shines in the dim lantern light. And who has lighted the lantern, for God's sake? 'When did you do all these, woman?' She asks, scarcely concealing her wonder.

Lutfa Begum has one or two rich people's habits drinking a cup of tea in the evening is one of them. Lipi runs to the kitchen to make her a cup, before she begins hurling abuses at her which, between the evening prayer and supper, are unstoppable. But an even more amazing spectacle awaits her in the kitchen. The place smells of freshly cooked food khichuri, fried fish, brinjal and potato curry. My God! When did she cook all these?

Dulal Mia usually eats his supper in glum silence, as if the food is not fit for human consumption. But today he is in a pleasant mood. 'Good cooking,' he says, 'but where did you got all these stuff?'

'The spinach is from the vegetable patch,' Lipi says, 'and the fish is from the pond.'

'Which pond?'

'The one at Mia Bari.'

'You went to Mia Bari for the fish?'

'No Father. I bought it from Painna's Ma the vendor.'

Dulal is happy. His son is now paying for the food. And this stupid girl is finally learning how to cook.

7. Time passes. Lutfa Begum's foot has healed, and her wrist is getting back some of its strength. She can do minor household work, even cook, which doesn't need full strength in any case. But she decides to play act for some more time. After all, her old bones need some rest. It is Lipi then, who continues to toil, although the time Renubala has set for the child's arrival is not too far. But in between her chores, she sometimes dozes off in the afternoon, when the earth become still, with scarcely a movement anywhere, and the wind blows with a low whisper, afraid to raise the sleeping dog in the yard; or in the evening, an hour before supper time, when the sky becomes dark and the moon hangs low, almost touching her. And while she slumbers on, all her household chores somehow get done. The same fairy-like girl, moving gracefully from kitchen to yard, from cowshed to pond, flashing a sweet smile at Lipi if she wakes up and their eyes meet. 'Sleep on, Ma,' the girl says each time, 'I'll take care of home.'

Lutfa Begum has to withhold her criticism of Lipi, much against her will, even give her a mild approval for a dish well-cooked or a sari washed to extra-whiteness, especially since Dulal Mia now finds Lipi a more acceptable daughter-in-law. This worries Lipi a lot. She is certain that the child in her womb is a girl, and it is she who does all the work for her. Then again, is she, or can she be certain? Who is it who can work so fast and so well? Not leaving behind even the tiniest loose end?

No, the question is not for you. It's not for us either. We know, a common sense answer would be: Lipi herself. An uncommon sense answer, on the other hand, would point at Gafur, since in his years in the middle east, he had to do everything himself from cooking to mending his shoes. But what if there is something else, beyond the common and the uncommon, something in the region of, say, the paranormal? What then?

There is no easy answer to this question. Let's forget about it then, and mind our story. Let's find out what Lipi is doing. What? She is crying? Why? Look at her she is crying disconsolately, as if she is the most wretched creature on earth. Her eyes are swollen, like a monsoon-fed river overflowing its bank. Why is she crying?

She is crying because she is now absolutely certain that the child in her womb is a girl. If the fairy girl is indeed her daughter, she must be one of the prettiest around. But Lipi knows, no matter how pretty she is, how fairy-like her figure is, how like champa blossoms her fingers are she will have to spend her life within the narrow bounds of the yard and the kitchen, the cowshed and the tubewell, squashed in turn by a long line of in-laws, and no less by the husband, consigned every moment of her life to hell by the battle axe of a mother-in-law. Is life a well, Lipi asks, an unmitigated, unredeemed stretch of darkness and descent?

The whole body of Lipi is convulsing with the force of her crying. Her legs suddenly snap, unable to bear the weight of an unwanted child, a monster of a child who is as unwelcome as a plague. She stretches her arms and grabs a bamboo pole. She sits leaning against the pole for a while, trying to compose herself. But her tears keep welling, and her voice keeps sounding hoarser. She feels unwell, as if all her energy has been drained out, and stretches herself on the cane mat. She has difficulty breathing, and her breasts keep rising and falling wildly. The sari end slips from her breasts and slides down to her side, revealing a long stretch of her body down to the belly button. The late afternoon sun pours its milky white light on Lipi's bare body, making it look white and radiant. Standing by her, Lutfa Begum feels a sudden burst of joy. For a moment she believes Lipi's end is near. She bends down to examine her. Yes, the glassy eyes, the foaming mouth, the sandy cheeks the signs are unmistakable. And her hands, how listlessly they lie beside her, and how her face looks deathly pale. Lutfa Begum silently waits for a spasm to begin. Any minute now, Lipi's body would shake violently. And then, the final whistle.

Dulal Mia, who has been observing Lipi from a distance, now hurries to her side, and squats, facing her. He looks at her face, shakes his head, and tries to lift her eyelid with his calloused fingers. There is no response from Lipi; the lid drops and closes on the eye as soon as he lets it go. His eyes now descend on her bare breasts, which look mellow and full. His hand shake as he tries to put Lipi's sari-end over her breasts, which he succeeds to half cover. His hand now rests on Lipi's womb. 'O Gafur's mother, is our grandson alive? What do you think?' he says. 'What's the problem with you, woman?' His question is now directed at Lipi.

But Dulal Mia could as well ask himself the question. Because, that very instant, he feels a violent pain in his hand. It goes limp, the bone broken not less than at two places. 'O my God, dear God,' he screams, and rises to his feet, shaken to his very foundation. He stands on his feet for a second, then collapses on Lutfa Begum's shoulder. 'My hand is gone, Gafur's mother, take me to the hospital. Call Gafur. Call Moina Bhai. Call the whole village. Oooo.'

Lutfa Begum panics. Her face turns ashen. She gets hold of her husband and drags him to the yard. 'Let's get out of here,' she shrieks, 'she'll kill us all.'

8. The house has fallen strangely silent. Lipi rises, and folds her cane mat, then gets down to the yard. She spreads the mat under the clump of lemon trees, which gives out a sweet, reassuring smell under the pale white light of a low hanging moon. Lipi sits on the mat, and rests her head on the curve of a branch, and places a hand on her womb. As she feels her child move, she begins to feel happy. Then she starts to laugh. First gently, almost under her breath, then loudly, as if she has heard or seen something really funny. As fireflies fly around her, and insects whir, her laughter reaches a crescendo. Her whole body shakes and her eyes water. She has never laughed like this before. The strange thing is, she doesn't know why she is laughing. As she laughs, her worries dissipate. Her fears too. She is certain, the child is going to be a girl. But there is no problem with that. Let the child arrive: let her arrive with all her fears or fearlessness, her courage or lack of courage let her arrive with whatever she cares to bring with her. Lipi won't worry at all about her. The child has just broken her grandfather's hand, this time really badly. This act, too, shouldn't count. Lipi won't see this as a sign of her strength or power. She won't even think about who kicks whom and why. All she will do is spend time with her, telling her the stories of a lifetime. The rest the girl will take care of.

She places both her hands on her belly and says gently, 'O my daughter, my princess, my sweet little princess.'

Syed Manzoorul Islam is an eminent fiction writer. His Bangla novels and short stories including Tin Porber Jibon, Shukh Dukkher Golpo and Prem O Prarthonar Golpo have set quite a new trend in contemporary literature. A professor of English at Dhaka University, he writes with equal ease in English.

![]()