Bangla Literature,partition & Translation

From Kalo Borof to Black Ice: a translator's journey

Mahmud Rahman

|

Near the end of Mahmudul Haque's novel Kalo Borof, Abdul Khaleq reaches the Padma.

So this is what it looks like now. What a state!

The Padma has shifted its course quite far. A fleet of sailing boats can be dimly seen. There is nothing here of what he had imagined. It's all dried up, derelict. The name Louhojong flickers in his head like the lights of the distant boats bobbing in the water. Goalondo, Aricha, Bhagyokul, Tarpasha, Shatnol -he can hear a deep sigh rising up from the names of those ghats.

Abdul Khaleq had not anticipated this disappointment. What was the point of coming so far merely for a name Louhojong?

Abdul Khaleq approached the Padma chasing a memory from his childhood journey from Barasat to erstwhile East Pakistan. One December morning while visiting Kolkata a few years ago, I made my way to Barasat to seek out whatever I could find of Abdul Khaleq's childhood. By then I knew that those reminiscences were those of the author himself.

After a long, bumpy ride on the DN18 bus along Jessore Road, I stepped off at Champadolir Mor. I did not know if I would find the neighbourhood where Abdul Khaleq spent his childhood as Poka (his nickname), but I was confident I would locate Hati Pukur (a pond in the novel). Large public ponds do not disappear easily.

Indeed, Hati Pukur lay right behind the bus terminal. When I set my eyes upon it, I caught a gulp in my throat.

So this was what it looked like now. What a state!

In the book, Poka used to walk here with his hand held by his Kenaram Kaka (uncle). Hati Pukur was described as ringed by huge rain trees. There was a gazebo in a centre island reached by an iron bridge. Poka and his school mates traipsed around Hati Pukur soaked in the fragrance of bokul flowers.

The pond is still there, smaller than what I had imagined. The water was blanketed with algae and the bridge coated with turquoise-coloured corrosion. The rain trees still stood proud and magnificent, even though they had shed much of their leaves because this was winter. I looked up and they appeared to whisper a question: what brings you here?

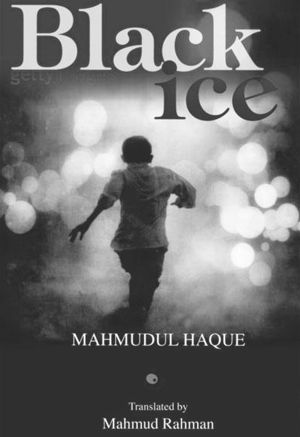

I had come on a kind of pilgrimage. I was then finishing the English translation of Kalo Borof. That journey reached a culmination recently when the translation was published as Black Ice by HarperCollins Publishers, India.

I became a fiction writer while living in the US. When I returned to Dhaka in 2006 for an extended stay to write a novel, I began seeking out Bangladeshi prose. Beyond the joy of reading, I felt this could add a new layer of complexity to my own writing. I often write about the same social context taken up by Bangla writers and it is helpful to absorb how Bangladeshis are written out by writers from within.

Soon after I arrived, I read an interview by Ahmad Mostofa Kamal of a writer named Mahmudul Haque. He was unknown to me, but he had apparently penned many novels and stories from the 1950s to the '70s before turning his back on the literary world around 1981.

I promptly went looking for his books. The search through New Market was futile. I had better luck at the December Dhaka Book Fair being held at Shilpakala Academy. From Shahityo Prokash I bought several of his books. The very next day I read the novel Nirapod Tondra. I scoured Aziz Market for more books, and soon I read the novels Matir Jahaj and Kalo Borof, along with the stories in Protidin Ekti Rumal.

I liked the writing so much that I wanted to translate. Mahmudul Haque deserved to be known outside those who read him in Bangla. I know the value of translated prose: I had been stimulated by fiction originally written not just in English but also languages like Portuguese, Gikuyu, Japanese. Why should the world not receive the best of our Bangla writers then? As a writer of fiction in English, I felt I could do justice to Mahmudul Haque's prose.

There was another interest. While absorbed in drafting my novel, I yearned to work with language on a different plane. Some fiction writers write poetry. I am not a poet. But I had once made an attempt at literary translation and enjoyed it. Here I could work with words and sentences at a close level in two languages. And because in my own novel I was rendering into English conversations of characters speaking in Bangla, I felt that translating might have a good effect on my book.

I began with the story Chhera Taar. The response to its publication in the Daily Star was encouraging. Next I chose the title story from Protidin Ekti Rumal. Dhaka is lax when it comes to author permissions, but I was reluctant to publish a second story without the author's consent. I asked around for his phone number.

I knew he was selective in who he let near him. I carefully rehearsed my line when I called. In a neutral voice, he heard me out and agreed to have me come over. When he let me into his flat in Jigatola, I sat in a room crowded with chairs, coffee and side tables, bookshelves, and a desk piled high with books and magazines. The book cases looked like they had lain undisturbed for a while.

He asked some questions to situate me. Once reassured that despite living abroad, I felt connected to Bangladesh, he opened up. We talked about his schooldays, his childhood ailments, the houses where he had lived, and his interest in animals. We touched on his writing and his not writing.

I asked for permission to publish the translation of Protidin Ekti Rumal. He waved his arm in dismissal I could do as I wished.

Returning home, I sent off the finished story to the Daily Star where it was published in an Eid Supplement. When I handed him copies, he was delighted.

When I brought up translating more of his writing, he retreated into the kind of response he had come to be known for: what does it all matter anyway? In fact, it was his wife, Hosne Ara Mahmud (Kajol) who encouraged me. She felt strongly the world should know his writing.

I began to visit every two weeks. He would not let me leave for four or five hours. I had come seeking support for translation, but he gave me much more: friendship. I sometimes wondered why. I think it was because I never pressed him on why he did not write. It may also have helped that I was someone exploring Dhaka's literary world without hardened attachments and prejudices. He enjoyed bringing to me a world I did not know.

Once I finished a draft of my novel, I decided to translate one of his books. I chose Kalo Borof.

Mahmudul Haque wrote Kalo Borof in a ten-day burst in August 1977. The novel was soon published in an Eid Supplement, but it didn't come out as a book until 1992.

I chose this novel because it is about Partition. Lost in our other preoccupations, we often overlook 1947. But that event played a momentous role in shaping who we are. Born in its aftermath, I come from a family only tangentially affected by it. I was familiar with some Partition narratives from writers who migrated to West Bengal, but I could find few stories of those coming east. Kalo Borof was the first novel I read that showed the long reach of Partition into a person's adulthood in Bangladesh.

The book's construction also appealed to me. Tightly composed, it is written in two alternating voices. One voice is intimate, the first person memories of childhood in Barasat. The other voice is in third person, slightly distanced; this one depicts Abdul Khaleq's adult life, his growing alienation, and the stresses in his married life.

From Ahmad Mostofa Kamal's interview I also knew this was Mahmudul Haque's favourite novel.

Six months after I started to visit, Hosne Ara Mahmud passed away. Stricken with grief, he moved to Lalbagh.

The tragedy spurred me to get moving with my translation. While working on it, I put aside phrases that stumped me. Some involved dialect, others were more of a mystery. I intended to take these puzzles to the author when I had finished a full draft. Meanwhile during my visits I tried to get as strong a sense of the novel as I could.

In a few months, I was ready with my list. On July 21, 2008, taking a break from cooking lunch, I dialled his number to let him know I would be coming over. A different man's voice answered. He said that Mahmudul Haque had died during the night.

The news hit hard. He had often talked about dying, but I paid him little mind. Though I knew he was in poor health, he had looked fine when I visited. I never imagined that death would visit this couple so suddenly, one after the other.

I wrote a tribute to the author and man who befriended me. Then I set about solving the remaining puzzles from Kalo Borof.

For a translator, an author's assistance can be immensely helpful. With the author gone, I had to draw in new resources. I reached out everywhere. Help with Oriya dialect came from a South Asian literary discussion group on the internet. Translators and writers I knew helped decode some Bangla dialect. I was down to one thorny mystery.

In the book, Poka and his friends come across a man who chants, Hambyalay jambyalay, ghash kyambay khay? What did this mean? No one I asked knew. The author's younger brother Nazmul Haque Khoka came to my aid. He vaguely remembered a saying from West Bengal putting down people from East Bengal. The words were attributed to Bangals' supposed confusion upon encountering an elephant: “A tail out in front, a tail while going, how the heck does it eat grass?”

The next step was to find a publisher. To gain a wider readership, I wanted the book published outside Bangladesh. Many excellent translations have been coming out from India for some time. During a literary festival in Dhaka, I had met Moyna Mazumdar of Katha, a Delhi based publisher. Eager to support my project, she connected me to Minakshi Thakur, an editor at HarperCollins, and Minakshi carried it the rest of the way.

When we put together the book last year, we included a P.S. section with an introduction to Mahmudul Haque. This includes excerpts from Kamal's interview. Minakshi was a pleasure to work with and with her keen eyes and strong instincts, she helped clarify and smooth out the final version.

I had failed to get written consent from Mahmudul Haque. In the end, their children came through. Both Tahmina Mahmud, living in Toronto, and Shimuel Haque Shirazie, living in Los Angeles, were excited to support the translation of their father's work.

With all the pieces in place, HarperCollins released the book this January. It has received mention and reviews in publications in Chennai, Bangalore, Lahore, Mumbai, and Delhi.

When I visited Barasat, I recalled that Mahmudul Haque himself never returned as an adult. Once during a trip to Kolkata, he agreed to go, only to change his mind and ask the car to turn back. He was still haunted with the pain of departure and preferred his childhood memories intact.

In recalling his life, it is hard to detach the sense of the tragic. The writer and his wife who I met at the start of this translation journey are gone. Last year his younger brother also passed away.

But those images of Poka's childhood in my head are etched deep. The reality of Hati Pukur did not make them vanish. Mahmudul Haque's writing remains alive.

What is the point of repeating lament? When we remember him, is it not better to celebrate what he gifted? I say, may more readers discover his books. May those who cannot read Bangla find him in translation. And may more translations come forth in coming years.

Mahmud Rahman is the author of the short story collection Killing the Water, published by Penguin India. He can be reached at mymood@gmail.com

![]()