| Spotlight

Tribute to T.S. Eliot Tribute to T.S. Eliot

Tribute to T.S. Eliot

This is a humble tribute to T.S. Eliot, one of the greatest poets of the 20th century, on his death anniversary that fell on January 4.

Eliot is one of the most read poets not only in the world but in Bangladesh as well. His poems and other works are a must read for the students of English literature. Here is a brief profile of the poet compiled on the basis of information available on the Internet.

“Thomas Stearns Eliot (September 26, 1888 January 4, 1965) was an American poet, playwright, and literary critic, arguably the most important English-language poet of the 20th century. His first notable publication, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, begun in February 1910 and published in Chicago in June 1915, is regarded as a masterpiece of the modernist movement.[4] It was followed by some of the best-known poems in the English language, including Gerontion (1920), The Waste Land (1922), The Hollow Men (1925), Ash Wednesday (1930), Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939), and Four Quartets (1945). He is also known for his seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and The Cocktail Party (1949). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Order of Merit in 1948.

Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri, and was educated at Harvard University. After graduating in 1909, he studied philosophy at the University of Paris for a year, then won a scholarship to Merton College, Oxford in 1914, becoming a British citizen when he was 39.

From 1898 to 1905, Eliot attended Smith Academy, where he studied Latin, Ancient Greek, French, and German. He began to write poetry when he was 14 under the influence of Edward Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a translation of the poetry of Omar Khayyam, though he said the results were gloomy and despairing, and he destroyed them. The first poem that he showed anyone was written as a school exercise when he was 15, and was published in the Smith Academy Record, and later in The Harvard Advocate, Harvard University's student magazine.

After graduation, he attended Milton Academy in Massachusetts for a preparatory year, where he met Scofield Thayer, who would later publish The Waste Land. He studied philosophy at Harvard from 1906 to 1909, earning his bachelor's degree after three years, instead of the usual four. Frank Kermode writes that the most important moment of Eliot's undergraduate career was in 1908, when he discovered Arthur Symons's The Symbolist Movement in Poetry (1899). This introduced him to Jules Laforgue, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine, and without Verlaine, Eliot wrote, he might never have heard of Tristan Corbière. He wrote that the book affected the course of his life.[8] The Harvard Advocate published some of his poems, and he became lifelong friends with Conrad Aiken, the American novelist.

From 1911-1914, he was back at Harvard studying Indian philosophy and Sanskrit. By 1916, he had completed a PhD dissertion for Harvard on Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley, about F. H. Bradley but he failed to return for the viva voce.

Eliot died of emphysema in London on January 4, 1965.

Poetry

For a poet of his stature, Eliot produced a relatively small amount of poetry. Eliot first published his poems individually in periodicals or in small books or pamphlets, and then collected them in books. His first collection was Prufrock and Other Observations (1917). In 1920, he published more poems in Ara Vos Prec (London) and Poems: 1920 (New York). These had the same poems (in a different order) except that "Ode" in the British edition was replaced with "Hysteria" in the American edition. In 1925, he collected The Waste Land and the poems in Prufrock and Poems into one volume and added The Hollow Men to form Poems: 19091925. From then on, he updated this work as Collected Poems. Exceptions are Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats (1939), a collection of light verse; Poems Written in Early Youth, posthumously published in 1967 and consisting mainly of poems published 1907-1910 in The Harvard Advocate,[22], and Inventions of the March Hare: Poems 1909-1917, material Eliot never intended to have published, which appeared posthumously in 1997.

The Waste Land

In October 1922 Eliot published The Waste Land in The Criterion. It was composed during a period of personal difficulty for Eliothis marriage was failing, and both he and Vivien were suffering from nervous disorders. The poem is often read as a representation of the disillusionment of the post-war generation. That year Eliot lived in Lausanne, Switzerland to take a treatment and to convalesce from a break-down. There he wrote the final section, "What the Thunder Said," which contains frequent references to mountains. Before the poem's publication as a book in December 1922, Eliot distanced himself from its vision of despair. On November 15, 1922, he wrote to Richard Aldington, saying, "As for The Waste Land, that is a thing of the past so far as I am concerned and I am now feeling toward a new form and style." The poem is known for its obscure natureits slippage between satire and prophecy; its abrupt changes of speaker, location, and time; its elegiac but intimidating summoning up of a vast and dissonant range of cultures and literatures. Despite this, it has become a touchstone of modern literature, a poetic counterpart to a novel published in the same year, James Joyce's Ulysses. Among its best-known phrases are "April is the cruellest month", "I will show you fear in a handful of dust"; and "Shantih shantih shantih," the Sanskrit word that ends the poem.

The Hollow Men appeared in 1925. For the critic Edmund Wilson, it marked "the nadir of the phase of despair and desolation given such effective expression in The Waste Land."[ It is Eliot's major poem of the late twenties. Similar to other work, its themes are overlapping and fragmentary: post-war Europe under the Treaty of Versailles (which Eliot despised: compare Gerontion); the difficulty of hope and religious conversion; and Eliot's failed marriage.

Allen Tate perceived a shift in Eliot's method, writing that, "The mythologies disappear altogether in The Hollow Men." This is a striking claim for a poem as indebted to Dante as anything else in Eliot's early work, to say little of the modern English mythologythe 'Old Guy [Fawkes]' of the Gunpowder Plotor the colonial and agrarian mythos of Joseph Conrad and James George Frazer, which, at least for reasons of textual history, echo in The Waste Land.[27] The "continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity" that is so characteristic of his mythical method remained in fine form.[28] The Hollow Men contains some of Eliot's most famous lines, most notably its conclusion:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

From the Sacred to the Holy: From the Sacred to the Holy:

Eliot Remembered

Shamsad Mortuza

Expecting a bomb or angel through the roof,

Cold as a saint in Canterbury Cathedral,

This gentleman with Adam on his mind

Sits writing verses on cats that speak: lives

By the prolonged accident of divine proof,

A living martyr to the biological.

Hell spreads its horrors on his window blind

And fills his room with interrogatives.

--“To T. S. Eliot” by George Barker

(1913-1991)

“After their deaths,” noted literary critic Michael Schmidt observes, “writers tend to suffer a revaluation, first (in the immediate aftermath) overvalued, and then knocked down a few pegs.” According to Schmidt, the editor of the influential PN Review, Eliot's reputation had experienced a serious devaluation ever since he died in 1965. Accusations of racism, misogynism, fascism, emotional coldness, and anti-Semitism dented Eliot's fame to a considerate extent. The poet of The Waste Land and Prufrock came under scrutiny after his conversion to Anglicanism in 1925 and after his political U-turn to conservatism. Ash Wednesday (1930) seemed to epitomize the metamorphosis of a poet who fit the bill of being a cosmopolitan dandy with Puritan ancestry, the American expatriate who was more 'English' than the English. Eliot's change from an avant-garde who ushered in modernism to England along with Ezra Pound and James Joyce to a liberal royalist and neo-classicist perplexed his friends and admirers alike. The floor-crossing was indeed out of tune with the overall mood and temperament of the time that was beginning to see the inadequacy of organized religion in dealing with spiritual and political stupor following the World War. They missed the old Eliot who championed the primitive energy of the sacred in the mythology of Joyce and D.H. Lawrence and who brought the message of datta dayadhvam damyata from the Upanishada. Instead, the latter Eliot became a naturalized citizen of Britain, began to receive accolades from the establishment that he once denounced. The list includes Order of Merit, the Nobel Prize, and even a commission to translate the Bible. Surely the rough feathers of Eliot have been smoothened by some divine provisions.

Biographers of Eliot have pointed out his troubled first marriage from 1915 with the ballet-dancer Vivienne Haigh-Wood as the source of his unhappiness ('the marriage trailed sin like snail slime'), and his consequent baptism. It was a marriage that his parents never approved, and which contributed to the emigration to England. No wonder Virginia Woolf once said: “He was one of those poets who live by scratching, and his wife was his itch.” It is quite ironic that a poet who earned his label as a critic for his urge to separate the text from the personal account of the poet is now being judged by biographical vignettes. In his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent” (1919), which formed the basis of New Criticism, Eliot forwarded the idea of the 'impersonality.' He thought 'the more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the man who suffers and the mind which creates.' But the detachment of the author from the work is no longer an option.

Thomas Stearns Eliot was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1888, the seventh and youngest child of a eminent family of New England origin. Eliot's forebears included the Reverend William Greenleaf Eliot, founder of Washington University in St. Louis. Isaac Stearns on his mother's side was one of the originalsettlers of Massachusetts Bay Colony. Henry, Eliot's father, was a prosperous industrialist and his mother Charlotte was a poet. With such a pedigree, he was almost destined to study at Harvard, which he attended between 1906 and 1910. He took a 3-year BA degree in comparative religion, and went on to do his Master's in English. He started working on his doctoral thesis on European and Indian philosophy, but never finished it. (Well, he wrote his thesis while in England, but was reluctant to return to Harvard for the defence). He taught at Harvard for two years, but disagreed with the idea of teaching religion without philosophy. After a sojourn to Europe, in 1915 he got married to Vivienne and came to London during the War.

The couple stayed with Bertrand Russell in his London flat. However, a brief affair between Russell and Vivien soured the relationship. Eliot took up a job first as a teacher in a junior school in Highgate, and then as a clerk at Lloyd's Bank, and finally as a publisher at Faber and Faber.

It is in London, Eliot met Pound and got introduced to Imagism and Italian Futurism. Although he did not associate himself with the imagists, Pound helped him pare down his language to economise its impact. Along with another imagist poet, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), Eliot took up the editorship of Egoist and catapulted himself in the London literary scene. His publication of Prufrock and Other Observations (1917) gave him immediate recognition as a poet. In 1922, he founded the literary magazine Criterion and published The Waste Land, and changed the landscape of English poetry for generations to come.

Interestingly, once established as a literary don, he began to recant some of his earlier radicalism. His poetry list published from Faber and Faber, notoriously omitted lines from his earlier poems, and tamed his mannered eroticism and political undertone. In the essay “Religion and Literature” (1935) Eliot stated that 'literary criticism should be completed by criticism from a definite ethical and theological standpoint.' For the early Eliot, however, the poet was like a 'witch-doctor' who had the ability to fuse 'the old and obliterated and the trite, the current, and the new and surprising, the most ancient and the most civilised mentality.' Eliot grounded his arguments on anthropologists such as Frazer, Lévi-Bruhl and Jessie Weston in order to claim, 'poet is older than other human beings.' With particular allusion to Lévi-Bruhl, Eliot added that the drumbeat of the 'savage' was the rhythm and percussion of the original drama; the 'auditory imagination' of the poet 'is the feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the conscious levels of thought and feeling, invigorating every word; sinking to the most primitive and forgotten, returning to the origin and bringing something back, seeking the beginning and the end.' Thus in Eliot's view, the challenge for the modern poet was to trace the pre-logical instinct in the likeness of a shaman. Hence, we have the 'sacred' figures of Lazarus or Sibyls of Cumaen in the early Eliot that seems to disappear in his 'holy' play Murder in the Cathedral or his Sweeney Poems or his The Confidential Clerk. The following excerpt from the play on the death of Becket can even be seen as a pamphlet of fundamentalist:

A martyrdom is never the design of man; for the true martyr is he who has become the instrument of God, who has lost his will in the will of God, not lost it but found it, for he has found freedom in submission to God.

Human kind cannot bear very much reality.

It is hard to believe that it is the same poet-critic who once hailed the 'mythical method' of Joyce, and viewed myth as 'a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history,' and added that myth makes 'the modern world possible for art.' But the mythic order was soon to be replaced with an Order of the British Empire.

Sir Eliot's latent racism can be detected in his less guarded remarks. Talking to the Indian novelist Mulk Raj Anand, he wished that 'Indians would tone down their politics and renew their culture. . . . We might gain from India - if it remains in the Empire.' His anti-Semitism is evident in his poem 'Burbank With a Baedeker: Bleistein With a Cigar.' In an interview, the older Eliot responded to the critics who viewed him as a poet of the 'disillusionment of a generation,' saying: 'I may have expressed for them their own illusion of being disillusioned, but that did not form part of my intention.' His Prufrock is replete with sexist aversions. After his baptism, Eliot started seeing sex as sin that led him to withdraw from the eroticism of his early poems.

So what are we to make of Eliot today? The syllabuses of the English departments still hold Eliot in high esteem. For many of our English departments, modernism both begins and ends with a slice of Eliot. So how can we critically engage with a poet who is as enigmatic as his persona (i.e. Prufrock)?

The short answer is Eliot is as contemporary as fresh as he was at the beginning of the last century. The power of Eliot lies in his language that resides in our aural memory.

The touch-and-go movement of his poems leads the readers through different landscapes. The Waste Land, for example, is a promenade of London. We join the poet in his site seeing of the Strand, the eastward river walk towards City and Lower Thames Street, the London Bridge up to King Williams Street, past the churches of St. Magnus Martyr and St. Mary Woolnoth.

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

(The Burial of the Dead, The Waste Land)

P.S. I often blame my experience of studying literature for ruining my innocence as a reader. When I approach Eliot today I feel there is a third person involved in the poet-reader platform (as was once famously said by Lady Diana about her marriage). Isn't it Eliot who said:

Who is the third who walks always beside you

When I count, there are only you and I together

But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another one walking beside you

Personally, on the first day I walked into the Department of English at Birkbeck College in London for my maiden meeting with my supervisor, I saw a plaque that told me that it was the very building in which Eliot used to work for his Faber Press. Then next door to my professor's room at 46 Gordon Square, I came to know of the Bloomsbury group and the cafes in which Eliot used to frequent along with Woolf and Joyce. The energy I received from the places helped me pursue a doctoral degree in contemporary British poetry. Although I learnt to debunk the Eliotesque brand of modernism during the course of my research, my appreciation for early Eliot has deepened. I can visualize Eliot, as Robert Grave has put it, as a 'startingly good-looking, Italianate young man, with a shy, hunted look, and a reluctance to accept the most obvious phenomenon of the daya world war'.

(The writer teaches English at Jahangirnagar University)

Eternally imprisoned emotions

Shayera Moula

We as a society fail to grasp the beauty of literature, throwing it away as some overrated commodity useful only to the aimless wonderers. But literature is that garden of emotion, which in its aesthetic power grabs hold of truth more than anything else in the world. After all, literature is history. Literature is society. Literature is human. Not only does it poke at those very personas of life in which we dwell in but we are assured that some things are eternally existing. Love, insecurity and dilemma happen to be just some of them. We as a society fail to grasp the beauty of literature, throwing it away as some overrated commodity useful only to the aimless wonderers. But literature is that garden of emotion, which in its aesthetic power grabs hold of truth more than anything else in the world. After all, literature is history. Literature is society. Literature is human. Not only does it poke at those very personas of life in which we dwell in but we are assured that some things are eternally existing. Love, insecurity and dilemma happen to be just some of them.

In T.S. Eliot's The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, the guide of a modern man's journey in a disarrayed city is that very feeling one can share even today, a hundred years later. The toxic smoke perfumed within an industrial city reflects the pollution that surrounds us today. The lonely streets and that "paralysed patient" mirrors the helplessness that surrounds every young city dweller so much in love, so much in fear of being rejected by love. And that very indecisive cat snuggled outside the house, afraid yet willing to go inside, embraces the eternal dilemma of whether to step into something unknown. Prufrock's fear to face these women, not just one but many, is again the insecurity of a modern man. Remember, in his poem he fears these very women who talk about Michelangelo, the very symbol of manliness.

The modern man is not one who is bold and courageous. The modern man is one who calculates his emotions, his chances and his options before making a decision. Much of what society has become today is methodological. We calculate the result even before we approach the matter. The modern man is not one who is bold and courageous. The modern man is one who calculates his emotions, his chances and his options before making a decision. Much of what society has become today is methodological. We calculate the result even before we approach the matter.

Along with the fear of rejection lies the fear of judgement. Prufrock is then the mock hero who in his indecisive situation is scared of being judged. He knows that upon entering the party, the many pairs of eyes will "fix you in a formulated phrase," where they will dissect every part of him, like those insects "sprawling on a pin". In today's world of profession and perfection, we are more so in that constant terror of being critiqued. T.S. Eliot thus in describing a world of fragmentation, with himself dislocated from his society, haunts upon us our daily lives and our daily habits to impress our surroundings.

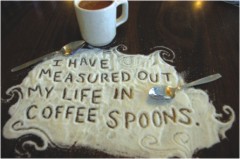

Then there lies the apprehension of "disturbing the universe," an emotion embedded within all of us. We refuse to accept change, and 'time' is that one factor that gets in the way of it all. The poet in his poem reminds us of him balding as if remind us of how we are constantly scared of aging. To measure out our life with "coffee spoons" seems nothing but a calculated waste of time assisted with a commodity, and more than anything else in the world, us human beings are scared of wasting our lives.

And so T.S. Eliot remains not just a Modern poet reflecting humanity and the world as he saw it, but as someone who echoes to us humanity as a we see it even today.

Writer studied English literature at BRAC University

|

Copyright (R) thedailystar.net 2010 |