|

Post Campus

Do Education Institutes Promote Creative Thinking?

Asrar Chowdhury

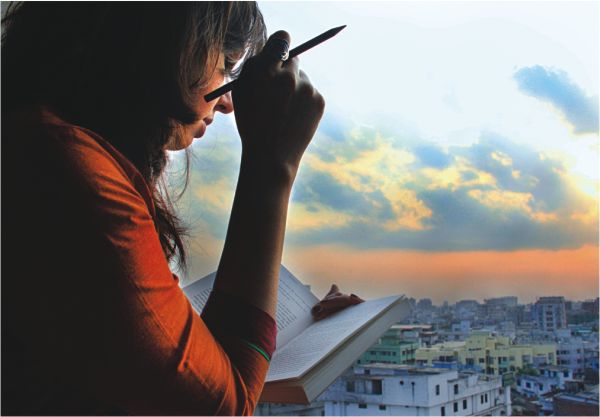

Photos: Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo

Have you ever experienced a situation where in an exam you were asked to come up with more than one answer to a single question? Alternatively, an exam where a single question could be answered in more than one way? Evidence from education research suggests that by the time a student graduates from university with a Bachelor's degree, he/she will have experienced at least 2,000 exams, quizzes and tests. The irony is that almost each and every test focused on coming up with the correct answer and/or where a single question had only a single answer. This finding is not concentrated to a particular country. It is a global phenomenon that has only recently caught the attention of education researchers.

The consequence of the above is simple. Rather than stimulating their creativity to discover answers and asking their own questions, students get obsessed in finding 'the' answer to a question. This forces them to reproduce verbatim what they have been told in class, what is written in their referred textbook(s) or what they think is in the mind of their teacher. Focusing on 'the' answer to a question or problem discourages creative thinking. Creative thinking is based on the presumption that a learner will make mistakes, reflect on them and then move on. Presuming that a single question has only a single answer further discourages the quest to extend the boundaries of knowledge. Presuming a single question has only a single answer also discourages students to respond to a question if there is uncertainty in the answer being 'the' answer.

The challenge to make an education system creative is easier said than done. Nevertheless, it is one challenge that education institutes around the world need to address. Today's young people are growing up in a world that is changing faster than at any point of human history. The only thing that can be predicted with a high degree of certainty is that it will be different. In such a world, rote learning is redundant. Students will need to be able to think creatively and come up with answers (yes, in the plural) to a single question.

To achieve this end, education systems will need to promote creative learning by encouraging mistakes and not just tolerate them. Contrary to conventional wisdom, great minds should not necessarily think alike. Surely, one of the greatest gifts an education institute can give to students is the opportunity to diverse views, ideas and perspectives. A simple yet powerful mechanism has to emerge that can identify creative thinkers and reward them, and one that is not so radical that it nips the bud.

Developing a creative education system becomes more challenging since education is delivered in a classroom that consists of students with wide range of intellectual aptitude. Funders and financers of education in the public and private sectors respond to enrolment rates and pass rates more than they do to promoting creativity. Students enter education institutes as a stepping stone to move on to professional life. With so many diverse factors inter-playing at the same time, promoting creativity in education institutes becomes more and more challenging. Having said so, education institutes do have a responsibility to identify those who will challenge the boundaries of knowledge, and with this challenge one day, will extend the boundaries of human experience.

By now the reader has probably got the impression that the single question on how to make education institutes promote creative thinking alas does not have a single answer.

At Cambridge I had a very interesting experience that I think would be relevant to the present context. On being appointed to 'tutor' undergraduates as they say at Oxbridge, our own tutor treated us lunch. During lunch he briefed us on how to approach undergraduate tutoring at Cambridge and what the system expected of us. At the end of the discussion, the Cambridge Don summed it all up - “Everything should be as simple as possible. Simplicity is more complex than one would like to imagine”. None of us understood what he said. He concluded, “Questions in an undergraduate exam are better set open ended than narrowed down. Narrowed down questions restrict the freedom to imagine. For instance the question 'what is demand' is open ended. The response to this question is in the plural. There is no single answer to this question. Those who are truly creative enough to challenge Alfred Marshall and all the other grand maestros to the task can answer this question just as much as those who want to go through the motion for the sake of it can also answer. Keeping questions open ended helps identify who are the truly creative in a group”. A very powerful statement, indeed!

Keeping this in mind, recently I experimented with this notion in an Intermediate Microeconomic Theory course. The class was briefed that questions would be open-ended. During the exam one student came and said the question that has been framed has multiple ways to answer. I smiled back at the young man. He came back and asked me this time, 'Surely there are multiple ways to answer the question, but which one is more correct'? I was expecting this type of a response. This is exactly the response students make to education research when faced by multiple answers to a single question. The exam finished. I was surprised. Some of the students wrote so creatively. By creatively I mean analytically and presenting theory with proper interpretations that went beyond what was written in the text and certainly beyond my class lectures. By keeping the questions open ended it was possible to separate the best from the rest and open up the minds of the students. Indeed, isn't that what education institutes are supposed to do?

How to make education institutes promote creative thinking is a complex issue that has recently captured the imagination of education researchers. In the practical world, a single question or problem never has a single answer or solution. Whether a solution will work is a function of time. In spite of all this, methods that have stood the test of time do tend to be the more simple ones. Simplicity has a wonderful power to be able to adapt with changing situations. Keeping things simple, but open ended could help education institutes around the world promote creative thinking.

(The author teaches economic theory at Jahangirnagar University and North South University.)

Source: Parts of this Post Campus drawn from “Why the education system is damaging creativity” presented by Gerard Darby for Four Thought of BBC Radio 4, first broadcast January 25, 2012; www.bbc.co.uk/ podcasts/series/fourthought/

|