| Spotlight

The open space in the Japan Garden City premises is a haven for young people and children.

Pitching

for Playgrounds

Sabhanaz Rashid Diya and Promiti Prova Chowdhury

Photos: Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo

I have a dynamite of a four-year old niece and she happens to like swings. That comes naturally for all children of her age, especially when she has spent an ample time of her life in Toronto with a playground at her backyard. On her recent visit to Bangladesh, she insisted I take her to a playground. I still cannot forget that desperate Friday afternoon. My best friend, brother and I spent over four hours driving from one end of Dhaka to another, looking for a decent place to play. To our epiphanic shock, we couldn't find a single space that's got green grass, a couple of swings, seesaws, slides, monkey bars and a bunch of happy kids playing in a safe environment.

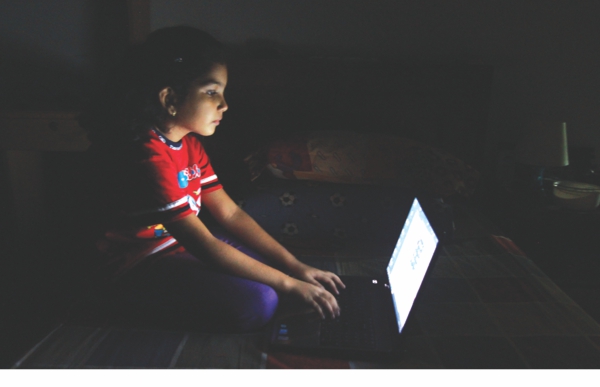

Children need to be taught how to balance between study and play.

Had it not been for that afternoon, the fact that a growing megacity like Dhaka still has not facilitated secure, public playgrounds for children would have never hit us this hard. In a 2012 UNICEF report on Children in an Urban World, it has been estimated by 2050, at least 7 out of 10 people will live in an urban setting. Population trends over the last few decades have shown nearly half of the world's children live in urban areas. Bangladesh's urban population stands at 4,170,000 since the beginning of 2012, of which nearly 30 percent comprises of children below the age of fifteen.

As buildings become taller, families smaller, spaces slimmer and populations larger, the necessity of addressing urban children with greater attention becomes predominant. The development sector has focused greatly on urban slums, however growing concern comes with children from the booming middle class. Having come from a slightly better off socioeconomic background that usually doesn't fit the bill of most high-end aid projects, the life of the typical urban middle-class child is left undisclosed. Most parents leave for work, the children for school, and afternoons are dominated by Doremon or computer games within 8-by-8 spaces. While there are a number of fields around the city, some public while some within restricted colonies, it is common knowledge they are disneylands for drug dealers instead of children. A drained routine of school, homework, computer games, television and perhaps, some level of play at roofs overpower their lives – slowly leading to a generation of socially exclusive, uncreative and essentially, unhealthy individuals. As buildings become taller, families smaller, spaces slimmer and populations larger, the necessity of addressing urban children with greater attention becomes predominant. The development sector has focused greatly on urban slums, however growing concern comes with children from the booming middle class. Having come from a slightly better off socioeconomic background that usually doesn't fit the bill of most high-end aid projects, the life of the typical urban middle-class child is left undisclosed. Most parents leave for work, the children for school, and afternoons are dominated by Doremon or computer games within 8-by-8 spaces. While there are a number of fields around the city, some public while some within restricted colonies, it is common knowledge they are disneylands for drug dealers instead of children. A drained routine of school, homework, computer games, television and perhaps, some level of play at roofs overpower their lives – slowly leading to a generation of socially exclusive, uncreative and essentially, unhealthy individuals.

Very little research has been conducted as to why Dhaka cannot facilitate safe playgrounds for children. It is easy to assume our hereditary distrust in the city's security, maintenance and capacity are key factors. Yet, findings from the past couple of years revealed a surprising trend. A recent report from BRAC explained how the concept of 'playground' is still largely unfamiliar to most of Bangladesh's population. While 'fields' to a foreigner may merely seem like places where boys play football, girls skip ropes and younger children aimlessly run around, to the average Bangladeshi, playground means just that. The Western concept of a secured space designed specifically for children with colourful swings, seesaws and other play items is as alien as UFOs, and therefore, a strong communal 'cultural shock' towards the 'perfect playground' is prevalent in most urban areas in the country.

Going Crazy! – develops the mind, body and soul.

The substitute and popular choice hence are public fields. Sixty-five year old Shahabuddin Ahmed Sentu is one of the founding members of Abahani Limited that proudly hosts the Abahani Field in Dhanmondi. He often brings his four years old granddaughter Irama to Abahani, where she has found a new friend, six year old Pushpita. Watching the girls kick around a football seems like a refreshing sight to Sentu Chacha. “I want my granddaughter to be interested in sports,” he confesses. “It will not only make her healthier, but also teach her discipline and socialisation skills. I feel trapped inside our contaminated food and water, and even air. Just coming out here at times and breathing under the open sky is a rewarding experience for both of us.”

Young girls should be encouraged to participate with friends in a safe environment.

The Abahani Field is open for all with people jogging, playing, walking and unwinding inside its vast premises. Amalesh Sen, ex-footballer and coach of the National Abahani team says, “Our members practice between 8 am and 10 am, and from 3:30 to 5:30 pm everyday. Anyone else, be it children, students or adults, even members of other sports academies are free to enter our premises except during our practice hours. We really envision more people getting into sports!” In the same vein, Dhanmondi Women's Sports Complex, designed especially to provide girls with a safe space to practice different sports, offers courses on swimming, aerobics, basketball and handball ranging between 1000 to 1500 taka per month.

However, while fields seem embracing, they aren't just as yet popular enough amongst the middle class.

Japan Garden City, a housing estate in Mohammadpur has an open, concrete 'courtyard' surrounded by looming skyscrapers. One of the few locations in Dhaka that has something remotely close to an open space where children can play, late afternoons and evenings at the estate buzz with children engaged in football, cricket, badminton and other games. Shafin and Shefali both go to Oxford International School, and were found chasing their remote-controlled helicopter around the courtyard at Japan Garden City. “We come here everyday,” explains a toothy-grinned Shafin. “We play hide-and-seek and sometimes bring our PSPs that we can play while walking. However, my sister has to go to a coaching centre every day, so she cannot come and play with us.”

A proper backyard playground is a dream come true for many.

No surprise there. The rising population has increased competition, fewer schools with even fewer quality teachers – and children spend, more than half their time, commuting between coaching centres. As twilight creeps in the dusty grey skies of Dhaka, children at Japan Garden City scurry towards their respective apartments, pressing the lift buttons and excitedly arguing which game they won. The concept of the 'perfect playground' disappears as quickly as daylight, and looming buildings with no breathing space take their place.

Cycling – not only enjoyable but also healthy.

So, what happens to the 'perfect playground'? Real estate agents and city corporations can be pushed to make secure playing spaces for children in the ground floor mandatory in towering skyscrapers. In other news, civil society can step in and create colony playgrounds with perhaps funding from the local private sector. However, as always, successful initiatives come from younger generations – the likes of you and me. A group of young journalists, engineers, architects and entrepreneurs have teamed up to create what they call Apartment Playstations. Designed within an indoor space, usually the abandoned office room at the corner of the garage, the group has been working to transform it into a 'playstation' using bright colours, recycled play items and activities. A small library comes with each playstation where children are encouraged to read, borrow and add books, mostly secondhand alongside weekend reading circles. The group's first pilot playstation will launch later next month, and from the late hours they've been pulling, it seems to hold great potential for a groundbreaking solution to an unaddressed problem.

An open space for the young is slowly becoming a myth.

While initiatives are needed, change truly begins with the self. As an economically and academically emerging population, Bangladeshis – sooner or later – need to start embracing the idea of playgrounds for children, and realise their importance in ensuring the healthy, creative and adequately socialising upbringing of their children. We still cannot imagine a day in our childhood where winter did not mean badminton or school did not mean the giant swings at our backyard. It's time children today and in future get to experience the same, if not better and grow up to write more positive articles with beautiful playtime memories than the one we just did.

|