Inside

|

Maria Chaudhuri writes from New York on the epidemic of domestic violence that so many Bangladeshi women who travel abroad for marriage are forced to endure

|

Lars Myhren Holand |

In South Asian culture, a good marriage is denoted by a partner of suitable economic and social status. Therefore, in the context of arranged marriage, a highly suitable partner is often one who lives and works abroad. It is pretty simple. In poverty-stricken Bangladesh, an ordinary man of limited education and capital can only get so far in life. What future can he possibly offer to his wife and children?

|

Lars Myhren Holand |

The same man, when in America, can have the same mundane job as a store clerk or a security guard, and yet, he neither lives in a slum nor perpetually struggles to make ends meet. The same man now has a shot at a fairly comfortable life because he has managed to cross the geographical confines of his indigence. Even those from higher income brackets are not without the assumption that a life abroad is a better life. Undeniably, the prospect of settling in the first world does come with some built-in boons such as better education, better-paying jobs, better medical care and more political freedom.

It is not unnatural that our vision of a better future should include social and economic betterment of our children. Unfortunately, we often try to accomplish these ends through means that are not necessarily uniform across the genders. While men are the go-getters of lofty goals, women are often encouraged to marry such ambitious men in order to reap the benefits. How many times have we heard someone say: "Sure, I want my daughter to go abroad for higher studies, but only if I can find a suitable boy who is well-settled over there."

A "foreign match" has now become the cherished target of an arranged marriage. If a woman receives a marriage proposal from a working man, settled in America or Europe, she is considered to have done even better than capturing that post-graduate scholarship for herself. Now, she can have all those good things in life (better education, better job, etc.), under the overarching and ultimate security of a "good marriage." What else is there to worry about? Well, plenty.

"The problem lies in accepting foreign marriage proposals without doing an initial background check about the individual. Due to pressure of time constraints, these marriages are often performed in a rush, and the bride arrives in the new country to find out that the groom is not what he or his family claimed him to be," says Margaret Abraham, Professor of Sociology at Hofstra University, New York, and former board member of Sakhi For South Asian Women, a New York based anti-violence organization that works to empower South Asian survivors of domestic violence.

|

Lars Myhren Holand |

Domestic violence is a term that many of us loosely associate with dire economic circumstances in some dark corner of a low-income area. Yet, it happens everywhere, even on rich American soil under the bright glare of the American sun, and we need to be aware of this. Drawn directly from my own experiences as former Legal Advocate at Sakhi, here are some real-life scenarios (all names changed) which illustrate the seriousness of the issue.

Dilruba was sixteen when Hasan's mother spotted her in their Mymensingh neighbourhood, and decided that she would make a suitable bride for her son in New York. Although Hasan was 14 years older than her, Dilruba's father, an old factory worker, happily accepted the proposal. Given his meager income and incapacity to provide any dowry for the groom, he decided not to prolong the matter by raising further questions. Dilruba was afraid to marry a stranger, but her mother said: "C'mon Dilu, do it for your old father so he can die in peace."

As Dilruba's father bought his ticket to a peaceful death, Dilruba bought her own to a hellish life. Hasan slapped her hard on their wedding night because she would not readily lift her veil and go near him. Three months later, when she stood at his doorstep in the Bronx, she hoped that the wedding night episode was just a bad mistake, and everyone makes mistakes. But Hasan's cruelty was no mistake. By the end of her first month in America, Dilruba had two black eyes and a bruised, aching back from the hard punches rained on her. By the end of her second month, she was working at two jobs, at two different food chains, while Hasan quit his job.

When Dilruba returned home after fifteen hours of work, Hasan would open the door and drag her in by the hair. He would then repeatedly punch her face and kick her hard in the crotch, accusing her of having illicit love affairs. A year later, when Dilruba was seven months pregnant, Hasan's tortures had not ceased. He would even yank the daily meals away from her, and bang her head against the dining table. Dilruba begged him to stop, to let her go, or to tell her what her fault was. She soon realized, though, that the fault was not in her, it was in him.

She did not know anything about him, his family or his childhood, but she knew that he wanted to kill her. A week before she was due to give birth, he kicked her belly hard and tried to stab her. She somehow broke free of his grasp, and he ended up stabbing her arm. Dilruba had three miscarriages due to the brutal beatings. She also tried to commit suicide, and regretfully mused that she should have taken rat poison instead of a bottle of Tylenol.

Rumana was excelling in her third year at Dhaka University when her elder brother arranged her marriage with Raihan. Although he did not know much about Raihan or his family,

Rumana's brother deemed it to be a perfect match. After all, Raihan was a professor and owned a house in New York. Raihan had even assured him that he would endorse Rumana's wishes to continue with higher studies.From outside, Raihan's house in Rego Park, Queens, looked decent with a nice-sized front yard. Inside, the house was worse than a shanty. Raihan had cut off the phone lines so he would not have to pay any bills, and nothing in the house had been washed, cleaned or changed in years. Raihan was as mean and miserly as a man can be. He did the groceries himself, and forbade Rumana to have more than one cup of tea a day. She had to have her tea without sugar, because that was one less thing to pay for.

Rumana often went hungry, because her meals consisted of a tiny portion of rice and spinach. She lost about five kilos in one month, and when she asked Raihan about getting a winter coat he gave her fifteen dollars. Rumana stayed home all winter, falling into a deep depressed confusion. Her husband earned a more than decent living, then why this torture? In the spring she reasoned with Raihan. She asked him to let her go back to school, so she could earn a degree and contribute to the household. Raihan laughed at her, long and hard.

He told her that he resented her for all the extra pennies she had already cost him, so going to school was out of the question. Rumana's dream was over. In the months to follow, Raihan revealed more of himself. He openly courted other women, and even brought some of them home in Rumana's presence. He seized all the jewelry that Rumana had received during the wedding, even her wedding ring. He told her that she and her brother were greedy beggars for planning to get a free ride through him, and he had made fools of them. He had married her because he needed a slave.

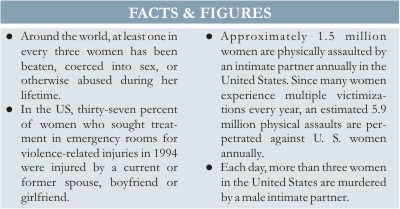

These stories are not anomalies. Around the world, at least one in every three women has been beaten, coerced into sex, or otherwise abused during her lifetime.1 The Raj and Silverman study2 of South Asian women (married or in heterosexual relationships) in Greater Boston shows that 41% of the respondents experienced physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime. In 2004, Sakhi received 581 new pleas for assistance, out of which 13.4% were Bangladeshi women, the third largest group, after Indians and Pakistanis. In 2006, Sakhi's call volume increased to 685, out of which 18% were Bangladeshi calls, making them the second largest group.

In the ordinary business of life, abusers are ordinary, polite, amicable men. But one must remember that abusers are some of the finest actors around us. "Research studies on domestic violence, and experiences of domestic violence incidents shared by survivors and community organizations, all point to manipulative ways that abusers exercise power and control. By being excessively nice to others, the abusers deflect any suspicion about abuse away from themselves, and can create doubts about the authenticity of the victim's claims," says Abraham. One also wonders why abusers who live away from the homeland go back there to choose a wife, sometimes more than once.

Sakhi has come across accounts where women discovered that their abusive husbands had been married before, and their divorced wives had been discreetly sent back home. Perhaps these abusers surmise that they have the best chance for deception in communities where they have had least activity. They also know that they run the lowest risk of facing any protest from their freshly-arrived victims, who are alone and totally inept at working their away around in a brand-new system.

Isolation is a key form of abuse for the immigrant woman, who is not only unfamiliar with the system but may be further handicapped by the inability to speak English. For example, even if a woman manages to call the police she is often unable to explain herself properly enough to get help. The abuser, on the other hand, knows the system well and knows how to manipulate his victim into subversion. Abusers commonly use the threat of deportation, or the denial of valid immigration status, to invoke fear in uninformed immigrants like Dilruba and Rumana.

Purvi Shah, Executive Director at Sakhi says: "The immigration reform debates have taken our country by storm lately. But the various positions have overlooked a key section of the population that remains undocumented, through no choice of its own: battered women whose abusive partners withhold valid immigration status as a method of control. In addition to threats of deportation, immigrant survivors may be kept in a limbo status by abusers seeking to manipulate a complex and overburdened legal system."

Families have a pivotal role to play in fighting abuse. While organizations like Sakhi help to inform women of their rights and help them navigate legal and other difficult arenas, they cannot offer women a real home to return to wherein they can start their lives afresh. Only their families can offer battered women this vital link in the process of breaking free. "It is important to include the judicial system in addressing domestic violence, but not to depend solely on the courts. Religious leaders must address the problem, and the media can play a great role in increasing awareness. Change can only happen through a multi-pronged approach," comments Abraham.

As long as men and women have unequal rights in society, the problem will continue. "After all, whether it is class, caste, race or gender -- those who have the power frequently define the way things should be, oppress, and have interest in maintaining the status quo," says Abraham. Permanent change will be thus initiated when we start to re-define the role of women in our culture, and negate marriage as the fulcrum of a woman's adult life.

If nothing else, let numbers speak the truth. Approximately 1.5 million women are physically assaulted by an intimate partner in the United States, annually. Since many women experience multiple victimizations every year, an estimated 5.9 million physical assaults are perpetrated against US women annually.3 In the US, thirty-seven percent of women who sought treatment in emergency rooms for violence-related injuries in 1994 were injured by a current or former spouse, boyfriend or girlfriend.4 Each day, more than three women in the United States are murdered by a male intimate partner.5

It is imperative to take these figures seriously, and to protect our daughters, sisters and friends from entering into relationships that can cost their lives. Under all circumstances, do not fail to investigate a foreign proposal exhaustively, and do not turn away should the marriage turn abusive. Each one of us can help -- start now by breaking the silence.

For specific information on domestic violence please visit www.sakhi.org