Inside

|

Why Mahmud can't be a pilot Naeem Mohaiemen reflects on the post 9-11 tensions of the Muslim immigrant diaspora in Europe and North America

2005. First warm spring day in New York. A group gathered at a West Village Italian: Bangladeshi professionals around the table, not my usual crowd of activists, artists, and troublemakers. Bonuses, overtime hours, conference calls, performance reviews, commodities, emerging markets, derivatives. As I listen to the flow of chatter, I search for words to hold on to -- a mnemonic device to keep me in the conversation. The occasion is the return of a few people from holiday vacation in Dhaka. A management consultant had gone home to get married and we are celebrating his return with new bride. Two decades back, when I came to the US, this sort of winter-migration was very common. People in Dhaka joked that these returnees were "winter birds returning for a bride." Over time this has shifted, as more and more women are also coming to America on their own, rather than waiting to arrive as somebody's partner. Of course, a sell-by date for marriage comes up for them even before they leave Bangladesh. There are myriad other restrictions and double standards as well. Even with all these restrictions, we have a roughly gender-equal table. Except for the new bride, every woman here originally came to the U.S. to study. But there are still strange rules about "appropriate jobs" for the women. Most of the men work on Wall Street, many of the women seem to be in marketing jobs. Temperamentally, the men are a bit removed from Michael Lewis's "big swinging dick"1 archetype, but they dominate the conversation. Everyone is bullish about things back in Bangladesh. Those freshly returned from vacation bring back excitement about a country going through rapid industrialization. Things are happening in Dhaka now, I'm thinking of going back. Our classmates are all becoming CEOs. The Indians are doing it, why not us? First India Shining, now Bangladesh Shining. A recent Time Magazine cover story, "Bangladesh: Rescue Mission,"2 seems to have done wonders. There's some grumbling in the politically savvy corner of the table that a Washington DC PR firm was hired by the Bangladesh government to plant stories like this. But still, good press is good press ... even if it is potted news. I enjoy the loose talk. They may all be masters of the universe, but it's hard to feel threatened by any of this. A Bengali Wall Street high-riser is not quite the standard testosterone cowboy. Besides all the colonial baggage (the ethnic group selected as "gentle" and "bookish" by the British Colonial project and raised to be the Empire's accountants, not its fighting force), there is also a latent cultural distrust of overt enthusiasm and energy. These are factors that serve to dampen any aggression emanating from the macho Wall Street ethos. Soon enough, many of these Bengali professionals will hear the "call" and depart the trading floor to return to Bangladesh and start their own companies.3 At some point during our dinner, we discover that our head-waiter is Bengali. After listening to our banter for a while, he finally decides to break cover and reveal that he's from Chittagong. His name is Mahmud and he's thrilled to find the restaurant's largest table occupied by compatriots. "This is an Italian place," he explains, "We don't often get Bengalis here. Actually never. Not spicy enough. Fika." Everyone takes a shine to Mahmud. He's self-assured, especially when explaining various wines to the table. Yes the Pinot is good, but not that year. Hmm, that other one has a smoky flavour. It won't go well with the fish. This one is from Coppola's vineyard. He's better at wine than film! Mahmud has no hang-ups about showing off his expertise to a table full of Bengalis. Some people at the table drink, others don't. But there's no pretense that some Muslim "standard" has to be kept. I'm reminded of the New York Times profile of one of the oldest bartenders in a stately Manhattan hotel -- a man who proudly told the reporter that studying chemistry in Bangladesh gave him the knowledge to mix drinks. But though he was quite comfortable talking to an American reporter, I wondered if he would be horrified if that story made it back to the Bengali press. Bangladesh is Bangladesh, appearances must be maintained. Goldman Sachs and Merrill Lynch. CBS and Ogilvy. After he leaves to bring dessert, I turn to our host. "Kothin obostha! That's a tough situation. Does he really think he can get hired as a pilot with that name?" "Don't be silly. Why should it matter? He'll be fine. Anything is possible." This is coming from a man who's a vice-president at his company. Equities or something -- I forgot what he said at the beginning of dinner. Flash back to a recent quote from Raju Narisetti: Anything is possible. A triumphant narrative of a dream life. No time to talk about the other half of South Asian America. No space given to conflicting narratives. Still there were some moments of unintended comedy. The former White House CFO gave the keynote and talked about how "decisive" George Bush had been since 9/11. A few moments later, the Muslim comedian followed and started railing against the "war on terror." An awkward silence descended on the room. A lone smile on my face.

Later, I searched through the speaker bios and organizer names. There were hardly any Muslim names. Of course my Muslim-dar is hardly foolproof. Before it became the vogue at the turn of the century for Bengali Muslims to have identifiably Muslim (read: Arabic) names, most people had Bengali names rooted in Sanskrit. Then there is of course the sizable Arab Christian population, perpetually mis-categorized. But with all those caveats, I felt reasonably certain I could identify Muslim students here by name. I tracked down the one Bangladeshi student on the organizing committee -- one of those solitary Muslim names. "Where are the Muslims on campus? Aren't they involved with these events?" I asked. "Well there are a lot of competing organizations and events. This conference is called 'South Asian' but the Muslim students see this as an Indian thing. So they just stay away and do their own events," he replied. Self selection, I thought, further back into self-imposed ghettos. On their way to becoming a permanent underclass. And why did the Muslim students feel 'Indian' meant it wasn't their space? Scanning the conference catalogue for Muslim names felt like an unexpected act of essentialism. Growing up in Bangladesh, religion is linked in my psyche with obscurantism and repressive state power. If you were a progressive of any stripe, religious parties were the enemy. You identified as Bengali or manush (human) first, not as Muslim. You said goodbye with Khoda Hafez, not the Arabicized Allah Hafez (although only in Bangla politics would such a trivial difference even matter). But transplanted across the globe, and facing many other cultural-ethnic vacuums that have developed over the last three decades, many Asian migrants seem to have slowly slipped into "Muslim" as a form of supra-ethnic identity. The Michigan episode seems trivial, but when I look at those students, I see contours of the future "best and brightest," and there are no Muslims in sight. Pre-law, pre-medicine, or pre-business by their second year, they are preternaturally professional and self-assured. A "summer job" is an internship at top-of-the-heap consulting firms like McKinsey. In fifteen years, these over-achievers will be running corporate America. But the missing names on that roster make me wonder who is being left behind. Or are they leaving themselves behind? Pop-sociologists look to religion for an easy formula to explain the stratified Asian underclass. But these equations obscure more than they clarify. In London, Bengali women are rarely seen working in non-family owned stores. Yet, in New York, they are a familiar presence in the service economy. Differing migration patterns are a bigger influence than religion. The bulk of the Pakistani and Bangladeshi migration came from rural and working-class communities in underdeveloped areas (Pakistanis from Mirpur and Kashmir, Bangladeshis from Sylhet).5 By contrast, the Asian migration to the US went through a restrictive filter of job categories, student visas, or family reunification, resulting in a more educated immigration pool.6 The Economist recently concluded that, even after 9/11, Muslims have better opportunities in the US than in Europe. In line with its ideological stance, the magazine lays the blame for Europe's "Muslim problem" on the mammaries of the welfare state.7 The problem, it seems, is the "excessive generosity" of the European state, which "encourages" Muslims to be lazy loafers. Dutch law professor Afshin Ellian posits: Five years ago, my Afghan sister-in-law emigrated to the United States, where she now works, pays taxes and takes part in public life ... In Europe, she would still be undergoing treatment from social workers for her trauma -- and she still wouldn't have got a job or won acceptance as a citizen.8 These formulations fit smoothly with the apocalyptic fears of British journalist Melanie Phillips, who talks about the growing danger from "home-grown Jihadis."9

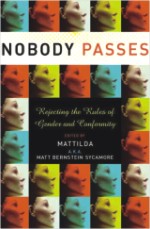

"Ambitious local kids feel themselves orphaned, doubly anachronistic ... So they flee ... In New York last year I found myself in a cab driven by a Bradford Pakistani who had spent the previous four decades working in a factory [in England]. 'Why did I stay so long there?' he cried. 'No opportunity, no future. Pure waste.'"10 Maybe things will be all right for Mahmud, after all? At least he's not in Europe? More of a future on this side? American dream, land of endless opportunity? Mahmud's would-be profession is one rare time that being a woman could reduce potential friction. In spite of the example of Leila Khaled and other female hijackers, the "terrorist profile" remains the Muslim male. This is not to say women are not checked at airports, but within a different calculation -- an "unknowing" mule or a seduced naif. So a Mahmuda may have a slightly easier time becoming a pilot. But then again, crazy patriarchy and power insecurities will trip up a female pilot in other ways. Back to our dinner. The evening ends well. We have a nice bit of banter with Mahmud and promise to return. Yes, please make a reservation in advance. I'll make sure you get the best table. We move on in search of nightspots. The out-of-towners want to go to a club. The rest of us pooh-pooh the idea of paying to get in. Only tourists do that. Our splendid unity is abruptly broken up by the cool factor. Meanwhile, what about Mahmud? Is he a crucible or an exception? Will he sail ahead unencumbered by a name, a presumed religion and national origin, or bump into a glass ceiling? If there is a growing societal consensus that Muslims, especially men, cannot be trusted with jobs in national intelligence, biological research, airport security, or air travel, how will he even know? Job discrimination no longer needs to be clearly enunciated. Quiet execution and a gradual sidelining is more likely. To take the long view, systematic race-based discrimination did not begin in 2001. Anti-black profiling is the original, well-worn template. The addition of a new "other" is only a slight variation in the formula. There is a slight shift in context as well. From drug dealer, criminal, and lazy worker to security threat, disloyal citizen and ticking time bomb. From driving while black to flying while brown. A short, strange trip. 1. Michael Lewis, Liar's Poker: Rising Through the Wreckage of Wall Street, W.W. Norton, 1989. 2. Rescue Mission, Time, April 3 2006. 3. For one example from Silicon Valley, see backtobangladesh.blogspot.com. 4. SAJA.org, interview by Deepti Hajela, April 14 2006. 5. Research by Tariq Modood and Richard Berthoud. 6. Until 1972, no visa was required for those coming to England from Commonwealth countries (this law was changed when Uganda's expelled Asians started arriving en masse). 7. The Diversity lottery visa that began in the 1990s widened the immigration pool from Asia, but even here there were minimum educational requirements. 8. Borrowing from the title of Upamanyu Chatterjee's novel in a different context. 9. "Eurabia: The myth and reality of Islam in Europe", The Economist, June 24, 2006. 10. Melanie Phillips, Londonistan, Gibson Square, 2006. 11. Usman Saeed and Sukhdev Sandhu, I'll Get My Coat, Book Works, 2005. Naeem Mohaiemen works in New York and Dhaka. This essay is adapted from a chapter in the anthology Nobody Passes: Rejecting The Rules of Gender & Conformity, edited by Matt Bernstein Sycamore, Seal Press, 2006. |

More nuanced writers, such as Sukhdev Sandhu, also detect signs of a transcontinental divide in opportunities. Exploring the devastated town of Manningham (scene of 1995 and 2001 race riots with Asian youth fighting police and white gangs), he documents the pervasive sense of dead-end life for Pakistani migrants:

More nuanced writers, such as Sukhdev Sandhu, also detect signs of a transcontinental divide in opportunities. Exploring the devastated town of Manningham (scene of 1995 and 2001 race riots with Asian youth fighting police and white gangs), he documents the pervasive sense of dead-end life for Pakistani migrants: