Inside

|

Rubaiyat Hossain discusses Rabindranath's willingness to subordinate to the cause of nationalism his liberal humanism when it came to the issue of women's emancipation

Madhurilata got married on the first of Ashar, Renuka is getting married on twenty first Srabon. Renuka is ten. When needed, the poet who once spoke against child marriage had forgotten all about it. Not as a poet, this time, he has been flawless and successful as a father. But the poet had to pay a price. For the next three months, not a single line of poetry came to him. Only prose!

-- Prothom Alo, Sunil Gangopadhay

|

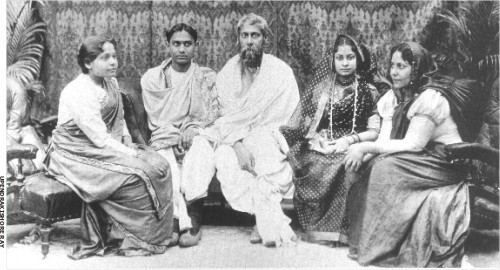

Rabindranath with his daughter Mira, son Rathindranath, daughter-in-law Pratima, daughter Bela. |

In Sunil Gangopadhay's historical fiction Prothom Alo, poet Rabindranath Tagore's remorse after marrying Renuka off at a young age with dowry money is depicted by a sudden spell of drought in his poetic career. That was Tagore's punishment for marrying off his young daughter. If we ask for what offense Renuka was banished to the fate of a young bride, we will not be able to find an answer. Renuka died a few years after her wedding.

Madhuri, Meera and Renuka, all three of Rabindranath Tagore's daughters were married off well before reaching even fifteen years of age. Historical references testify that Tagore was not at all happy with Renu's and Meera's matches. He paid heavy dowry for marrying all three of his daughters, but the dowry demand from Meera's and Renu's husbands remained a recurring theme. Madhuri died at the age of thirty-two in 1918 and Renu died at the age of fourteen in 1904.

It is worthwhile to ask: why is it that all the women in Rabindranath Tagore's family had tragic endings?

|

Rabindranath and his wife Mrinalini Devi, soon after their

Marriage, c.1883 |

Whereas Indira Chowdhury and Sarala Ghosal, two of Tagore's nieces, got married at the age of twenty-nine and thirty-three, respectively, which was quite the exception back in the early 20th century, why did Rabindranath Tagore refused to educate his daughters in Shankiniketan, or perhaps send them abroad to become educated and self-sufficient?

Why did he define their ultimate fates as marriage when clearly he had the understanding that these marriages were not going to work out for the girls' benefit? Why is it that Tagore never made an effort to educate his wife? Why does Mrinalini only appear as a self-sacrificing mother who sells her jewelry to save Shantiniketan from sinking?

Whereas Tagore's sisters-in-law were all educated, and even appeared in the public sphere, why is it that Tagore's wife lived a very uneventful and private life? She was married at the age of thirteen, bore five children, and died at the age of twenty-nine. Why is it that we see a clear diversion from Rabindranath Tagore's otherwise liberal humanist attitude when it comes to dealing with the social and cultural positioning of women in his life?

In order for us to attempt to understand this question it would be helpful to comprehend the idea of "individualism" that was created for Bengali middle class women of the 19th and 20th century. When interrogated against the back-drop of colonial political economy, the overall double standards of Bengali nationalism in creating the women's individuality will become clear.

Women were situated by 19th century Bengali nationalist imagination in the ahistorical, traditional, and spiritual domain of the home. The rules and logic that governed the public domain were questioned, altered, and reconstituted in the private arena of the home. I would like to illustrate this home-world, public-private, Western-Bengali dichotomy by analyzing Tagore's depiction of female characters in his literary work.

|

Two elder brothers of Rabindranath and their wives: Jnanadanandini and Satyendranath, Jyotirindranath (seated) and Kadambari. |

It is worthwhile examining whether or not individualism was banned for 19th century Bengali women through the newly constructed patriarchy that carried out the project of female emancipation against the backdrop of colonial political economy. Partha Chatterjee has spelled out the home/world, spiritual/material, private/public, East/West, and female/male dichotomy to locate the ahistorical, shastric, and self-sacrificing positioning of women by 19th century Bengali nationalism.

This nationalist project sought its unique, and superior, feature in the spiritual domain that was represented by the home, the private, and the woman, and identified it as the "inner domain of sovereignty." It is within this arena of nationalist imagination that the Western modernism was challenged and altered. This alternation was done through flipping the meaning of the word "freedom" for women with the intention of restricting them from fully exploring their individualistic wills and desires, thus sustaining the mechanisms of an extended joint family that demanded total subjugation, selfless sacrifice, and endless service from women.

The word was assimilated into the nationalist need to construct cultural boundaries that supposedly separated the "European" from the "Indian." The 19th century "Indian" interpretation of the word "freedom" differed from the one understood in the West: it was argued that in the West, "freedom" meant jathecchachar, to do as one wished, and the agency to self-indulge; in India, however, "freedom" meant being free from one's ego, and the capability to sacrifice and serve willingly.1 It is in the context of this selfless so-called "free" female individual that Tagore's interpretation of Binodini's character in Chokher Bali (1903) unfolds.

It is interesting to scrutinize the Binodini of Rabindranath Tagore's most celebrated novel, Chokher Bali, because this novel is hailed by critics as the foundation of the modern Bengali novel that "relied upon the detailed psychological method in which incidents and intentions are marshaled in a close array."2 Even though Chokher Bali goes furthest into interrogating the widow's interiority, and offers social solution to the widow problem from the point of view of a male author who came closest to constructing the widow as an active agent of her will and action, at the end, the novel returns to an ahistorical and transcendental understanding of the widow's sexuality as a strategy of aesthetic rebellion against the Western construction of modernity.

Sympathy, Dipesh Chakrabarty argues, derives from the application of reason to the human mind, and it creates a transcendental modern subject who "from the position of a generalized and necessarily disembodied observer" is capable of "self-recognition on the part of an abstract, general human being." It was this sympathy that enabled Tagore to assume the pains and complications of widowhood, and made it possible for him to seek the psychoanalysis of a widow's mind. Chokher Bali offers a special social space to an unfortunate widow, and follows the course of her agency in manipulating relationships in order to negotiate a respectable position within a patriarchal society.

The primary loop-hole in Tagore's construction of the widow's individuality is its ultimate limitation in comprehending the widow's individuality

based on her sexuality, and the employment of the poetic mode within the prose narrative to transform the widow's character into an aesthetic idiom that lacked objective and historical vision.The story of Chokher Bali evolves around the passionate love tale of four characters: Mahendra, Ashalata, Binodini, and Bihari. Tagore admits in the preface that the jealousy of Mahendra's mother Rajlakhsmi towards his wife Ashalata is the driving force of the novel, which creates the ground for Binodini and Mahendra's illicit love affair.

Binodini's marriage was settled with Mahendra, but because of his refusal to give in to the marriage at the last moment, Binodini was married to a wrong match, Bipin, who died only one year after their wedding. Binodini's primary jealousy around Ashalata is born out of her recognition of her own qualities to be a better householder than Asha, and unfulfilled sexual desire further flames Binodini's jealousy.

Bihari, Mahendra's friend, is introduced as a counter-force to Mahendra's selfishness and hyper-active sexuality. Binodini's love creates complete unrest in the family, and Binodini, being the product of enlightenment ideology, comes back to her reason and decides to fall in love with Bihari by understanding the wrongness and social impossibility of her relationship with Mahendra.

Bihari, however, refuses to accede to Binodini's proposal, and Binodini is struck by the ultimate triumph of her reason at the end of the novel, after Mahendra's mother Rajlakhsmi's death, when she simply leaves the scene of the Mahendra-Ashalata household, thereby making a rational choice that gives her the chance to be a modern individual subject.

The women's emotions in this novel, love and jealousy, are derived from their passion to master the masculine forces of the novel. The men's emotions, love and selfishness, are derived from their desire to own and master as many feminine forces in the novel as possible.

Bihari wins this race over Mahendra, because at end, Bihari's superior application of reason gains him respect from the overall female characters in the novel. Mahendra's mother Rajlakshmi jealousy towards Ashalata is based on Asha's complete mastery over Mahendra in the first part of the novel. Rajlakshmi's jealousy brings Binodini into the scene, and Binodini's jealousy against Asahlata, and prem (romantic love) for Mahendra pushes the narrative to a more complicated state where the total breakdown of moral and emotional equilibrium of the novel takes place.

At the denouement of the novel, reason rules over emotion for each character, and things reach a resolution with Binodini's departure from the scene. The word Tagore uses to describe the feminine emotions of love and jealousy is maya; women in this case are shown as mayabinis, creatures capable by their sexuality to manipulate and create instability in the masculine mind. Asha is shown as being naïve in the game of maya, as opposed to her mother-in-law or Binodini. The absence of the essential female power of maya in Asha's character makes her more benevolent than the others.

Tagore's understanding of maya is based on the same idiom as his nationalistic poetic mode described by Dipesh Chakrabarty, where the real nation portrayed in the prose language would transform itself into a poetic transcendental icon to mitigate the distance between the desired state of the nation from the actual chaos.

Similarly, the moral degradation of women in Tagore's novel is described in the prose language, but when he draws the conclusion, and locates the ultimate source of the moral downfall of the females, he delves into the realm of the ahistorical where the essence of maya and its uncontestable authority in the realm of the mythical provides a justification for the violent treatment of female sexuality.

Tagore's overall justification for isolating the feminine to the realm of the ahistorical is part of his larger project of aesthetic rebellion to the West, which is pronounced in one of his last plays Rakta Karabi (1926). It is one of Tagore's last pieces of work, and it focuses on the inherent struggle between agriculture and industrialization.

The play is set up in a place called Jokkhopuri, controlled by a ruler who is completely isolated and out of touch with the community. The air is heavy, and the inhabitants dig the earth all day long in search for minerals. Nandini is brought into the scene as the ultimate sign of force that can free the shackles of Jokkhopuri, diminish its evils of riches and intoxication, and restore freedom and foster closeness to the earth through agriculture.

Nandini, however, is established as a character who is always happy, and concerned about others. There is no personal wish that she attempts to pursue, except for the well-being of the community and waiting for her lover Ronjon who would eventually free the community. In Nandini's case, her innocence, and feminine spirit of caring is enough to shake the foundations of the ruler who is supported by his network of power.

Tagore in Rakta Karabi objects to the lust of the enormous power structure by resisting it with the character of Nandini, who carries the spirit of individual freedom and creativity; but the problematic aspect lies in Nandini's overly dramatic passion of sympathy towards the community.

As I have mentioned earlier, according to Chakrabarty, sympathy is crucial in creating a modern subject who is capable of feeling a universal position and, therefore, acting rationally towards others in the community. Another important aspect of the modern individual that Dipesh Chakrabarty points out is the interiority of the subject. This interiority is born out of the struggle between reason and individual desires, emotion and passion. Even though we see the expression of Binodini's interiority in Chokher Bali, Nandini's interiority is completely lacking in Rakta Karabi.

It was important for Tagore to show Binodini's interiority because, by the virtue of being a widow, she had already committed a social oddity. The only way she could ever render herself acceptable in the society was by fighting her passion, greed, and sexuality with the tool of reason, which opened up her mind to sympathize with Asha, Rajlakhsmi, Bihari, and even Mahendra in realizing the evils of her passion that ruined this family.

Nandini, being a virgin, is pure and less complicated. The spirit of womanly traits as identified by Tagore: spiritual love, spirit of service, passion for self-sacrifice are already present in Nandini, whereas in Binodini's character these qualities were burdened by the ills of her sexuality and passion to practice it. Binodini is Tagore's attempt to internalize the degeneration of the society, and offer a literary solution to the problem, whereas Rakta Karabi is completely set in a mode of poetry, in the poetic realm of ahistorical reality.

If Binodini was a problem and the nationalistic agenda had to seek a solution for her, then Nandini was the ideal iconification of feminine sexuality that was desirable as the foundation for India's nationalistic movement. Tagore's discussion of Rakta Karabi confirms that it is a "vision" that had come to him "in the darkest hours of dismay."3

By 1926, the first world war, growing communalism in India, proposals for partition, violence in the nationalist language prepared the ground of Tagore's poetic humanism to seek for an alternative solution that was to realize the "divine essence of the infinite in the vessel of the finite."4

This aesthetic journey ended in the complete objectification of feminine sexuality in the timeless, spiritual, ahistorical, transcendental, self-sacrificing realm of nationalism: "This personality, the divine essence of the infinite in the vessel of the finite -- has its last treasure-house in a woman's heart. Her pervading influence will some day restore the human to the desolated world of man."5

It is this heavy burden of embodying the true essence of the infinite in the vessel of the finite that caused Tagore's daughters to be sacrificed for the "traditional cause" of early marriages.

Locating this alternative spiritual superiority in the women enabled nineteenth century Bengali nationalism to impose clear double standards on its women. It is under this framework that women became the bearers and redeemers of the culture.

Rabindranath Tagore, who previously protested the practice of child marriage, opposed the Age of Consent Bill 1891, which raised the age of consent for sexual intercourse from ten to twelve. Nationalism and winning the ideological battle with the British was clearly far more important than saving young girls from marital rape.

The Bengali men did not want the British officials setting the rules in the bedroom too. The British had already been ruling the public sector for hundreds of years. The private sector was for Bengali men to lay down their own rules and brew the nationalist emotions to ultimately overthrow the British rule. The "women's issue" could wait until then. After all, women were spiritual beings.6

Clearly, it was more necessary for Rabindranath Tagore to create a social revolution in the public sector than to offer better lives to his daughters and his wife. However, this phenomenon does not seem to bother any of us, does it? After all, Bengali women are hailed for their ultimate power to self-sacrifice, both for the cause of the nation and for their men.

1 Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Provincializing Europe, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000.

2 Sarada, M, Rabindranath Tagore: A Study of Women Characters in his Novels, Bangalore: Sterling Publishers, 1988.

3 Tagore, Rabindranath, Rakta Karabi, Kolkata, Viswabharati: 1998.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 See elaboration of this argument in, Chatterjee Pratha, The Nation and its Women in Guha, Ranajit, Subaltern Studies Reader 1986-1995, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1997.

Rubaiyat Hossain is an independent film-maker and Lecturer at Brac University.