Inside

|

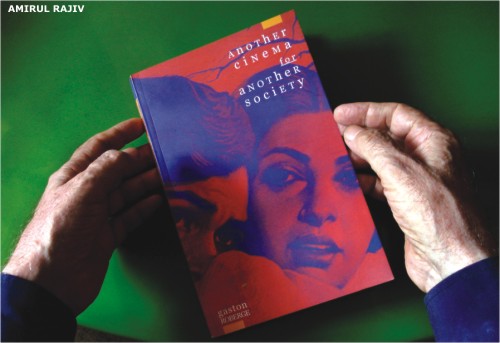

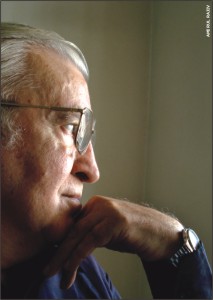

An interview with Father Gaston Roberge Film scholar Father Gaston Roberge talks about Indian film, Greek theatre and the power of the Internet in an interview with Amirul Rajiv and Ahsan Habib One of the top film scholars and critics in India, Father Gaston Roberge founded the Chitrabani media institute in 1970 with support from the late Satyajit Ray, and was a lecturer in film studies at the University of Kolkata before retiring in 2006. This interview was taken last month on the most recent of his many visits to Dhaka. You are a Jesuit, a member of a religious society. Why did you go to study films? The second reason I work in this field, I have been interested in films from a very young age. As a schoolboy I used to attend shows. There was no TV of course. But in the school we were shown serials of cowboys. I was very fascinated by those stories. After that, when I was about sixteen, I heard that a film society was being created in the city I was staying. I asked if I could join without knowing what it was about and then I discovered cinema. I saw many films prior to that as a sort of exciting dream. But once I joined the film society I discovered that cinema was much more than just fun. What interested you about film? What do you like best in film?

Perhaps I could say that even when I was watching the cowboy films as a kid, I experienced the power of cinema, which I understood only later. What I mean to say is that even if I saw films that we would consider of little worth, I was experiencing cinema even as a kid. This is very important to me because the films that the scholars tend to dismiss as worthless have something in them. And it should be the duty and responsibility of the film scholar and film critic to help people make the best of the film experience that they have -- even so-called commercial films. You spent your early days in Canada. Then in 1961 you came to Calcutta and experienced Indian cinema. How was it different from your earlier experiences of cinema? How much did it influence you? But I saw the Apu Trilogy in a particular frame of mind; namely, it was the last night before leaving my country for India by boat. I had to spend the night in a small hotel in New York and I looked at a newspaper like anybody would do and found that there were three films from Kolkata, being shown in an art theatrethree, not only oneso I thought let me see that because I was going to Kolkata. So I saw the entire trilogy, Panther Panchali, Aporajito and Apur Sansar in one seating. It had a tremendous impact on me. It was like introducing me to Bengal. I found the characters so lovely, so human that I was very fascinated. After that in the ship, it took nearly forty days sailing to Italy, going to Mumbai. So I had the time to think and it was as if I was creating my own panchali about the India that I was going to see. Even before that I thought with love about the people I was going to, but here it was more concrete. Did you find any difficulty with Satyajit's Indian characters as a man born and brought up in the west? You see what is happening in the Apu Trilogy is that the aporajito [unknown] is jibon [life] -- cholchhe cholchhe abar ashchhe cholchhe ashchhe cholchhe kono poriborton noi. Also, the death of Harihar is given much attention. In American films there are many deaths but nobody dies, whereas in the Apu Trilogy there are at least five deaths. Harihar has one of the most realistic deaths on the screen. It is death as part of life. Film scholars and critics tend to dismiss popular film as worthless, but the people are very interested in these films. How do you view this gap as a film scholar in the context of the Indian subcontinent? I mean I consider two types of films that the people see. Films that they enjoy and films that they somehow find meaningful. They love to see these latter films usually more than once. These are the films I am interested in because my guide is the public. People may be addicted to the frivolous enjoyment -- a little sex, a little violence, a little death -- but usually they do not see the same film twice. There is no need because after they have seen one they can see another. It will be the same thing, the same formula -- eight songs/dances, what not. Box office hits may not be really popular films. They are films that people see for fun. But the ones that people see for meaning are those I call popular. The reason why popular films are not always seen positively by academics, I believe, is because they see the film in the framework of a western theory of film as expressed by Aristotle two thousand years ago based on the great dramas of his time. I am convinced that if we want to understand the popular film we have to look at it from the point of view of the Indian subcontinent -- because two thousand years ago popular drama was not separate from high drama in the light of Indian art theory which is certainly not inferior to that of Aristotle. I encourage film scholars here to be a little Greek oriented. If we take dramatic structure positively, perhaps we can help the film industry -- the Indian and Hindi film industry -- to do a better job. If they have to put eight songs and dances in their films at least let there be something of quality. You have been writing on film and media for many years. During this time span massive changes have taken place, we are told of a 'revolution' in the field of communication. From Chitrabani to Cyberbani, how did you experience that revolution as a writer?

My book Cyberbani [2005] is not organised like a usual book. Now I am writing one that is more obviously built like the web. Eventually the text will be on the web also. It will be what you call copyleft, open source. There is a licence authorising you to copy it as often as you want as long as it is not to make business. You are also authorised when you take it to change it, make it better. Because the prevalent culture is a collaborative culture, though this is much impeded by the copyright system. We are always told to develop a "balanced view" of the world. But in Cyberbani you said, “Balanced views are not the views that change the world.” Would you please explain it? For action you must target specific facts, you cannot look at all the facts at the same time. Otherwise you don't change anything. You consider the negative side and want to improve it, so then it must be an unbalanced view. For instance, so many students waste a tremendous amount of time on the web. Immediately you can say that is true but others learn a lot from the web, so keep quiet! My approach would be, since many students learn a lot from the web, why not helping those who waste time to also learn. I take an unbalanced view to tackle the negative aspect, well aware that there is a positive aspect. What you want to mean by the term "media-oppressed" in your writing? This is one of the, I would say, problems of our time -- we do not know if we know what we should know. However, something new has happened, what you might call, parallel news broadcast through the Internet. While on the one hand the elite who control the media can to an extent control the knowledge that we have, we have now for the first time in human history, the means to resist false information. But it's not so easy; a lot more has to be done to educate our people as to the possibility of resisting and the duty of doing so. If we want to be free, we have to fight for it without hatred, quietly but efficiently. For instance, when George W. Bush declared war on Iraq, in a few hours, they say they say that over 10 million people worldwide went to the streets to protest. Ten million people, it is incredible. Of course they did not stop the war, but they can never say that they were not told. The very weapon -- if I may say that -- used by the power can be used against the power. If they can use the media, the people also can use the parallel media through the Internet.

The media environment has been structured in such a way that it divides people into those few who do/act and those many who watch/consume. How much space can the new media environment make for resistance to the present order? Self-education for liberation is an attempt to regain the freedom of mind. You can regain your freedom of mind any day you want. You are only to want it and do a little effort. Only those who are free can bring freedom to the world. Amirul Rajiv is Photo Editor, Forum |

However, I can say that the first film I saw as a cine film member disturbed me. It left me with a little uneasiness. You will find this strange, but that film was Battleship Potemkin. For maybe ten years some scenes would come back to my mind and I could not understand why. It was disturbing. Only when I studied Eisenstein I understood. Because he explained that the purpose of his making films is to plough deep in the psyche of the spectators.

However, I can say that the first film I saw as a cine film member disturbed me. It left me with a little uneasiness. You will find this strange, but that film was Battleship Potemkin. For maybe ten years some scenes would come back to my mind and I could not understand why. It was disturbing. Only when I studied Eisenstein I understood. Because he explained that the purpose of his making films is to plough deep in the psyche of the spectators. About ten years ago I became aware that people do not read books from start to finish as in the past, but because of the experience of reading web pages felt less inclined to read a, b, c, d. Already in 1978 I had hyperlinks in one of my book. I did not invent that; I copied it from a French encyclopaedia. But I found it interesting that every time in the text there was a verb on which there was an article, it was underlined.

About ten years ago I became aware that people do not read books from start to finish as in the past, but because of the experience of reading web pages felt less inclined to read a, b, c, d. Already in 1978 I had hyperlinks in one of my book. I did not invent that; I copied it from a French encyclopaedia. But I found it interesting that every time in the text there was a verb on which there was an article, it was underlined.