Inside

|

Published (defiantly) in the Streets of Dhaka Fakrul Alam runs an appreciative eye over the collected works of Bangladesh's finest English language poet

But that Haq is a very good poet, and capable of holding his own with most poets everywhere, should soon become obvious to any reader of his Published in the Streets of Dhaka: Collected Poems 1966-2006. Here, in this modestly sized and produced volume, the still-not-sixty poet who has been writing for over forty years now stakes his claim to be a major poet of his region. Consider "Windows," the first poem of the first of the collections assembled in the volume, which is titled New Poems: 2002-2006. At first glance, this conversation poem seems to be a slight achievement, presenting as it does the exchanges of a couple on their neighbourhood buildings, ghost-like in the gathering dusk one moment but lit up and full of people in motion the next. To one speaker, the denizens seem quite remote from them, but the second one notes that "those oblongs of light" were their home too. But doesn't the concluding stanza of this brief poem ("…Fragile Slates/On which we may adumbrate/Our unsteady kisses") remind us of the ending of "Dover Beach," where Matthew Arnold, famously confronted with a receding Sea of Faith, exhorts his beloved to understand that they should be true to one another since they were positioned "on a darkling plain/Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight/Where ignorant armies clash by night?" In fact, Kaiser Haq's stance as a poet is that of the rooted cosmopolitan. Willingly, and even defiantly, he bases himself in Bangladesh, but his mindset is that of a citizen of the world to whom, in an age full of chaos, the only stay against confusion can come through the seeking, restless mind. Haq, to put it slightly differently, refuses to be complacent, and opts either for communion with seekers everywhere or, aware of the inanities of the quotidian and the vanity of human wishes, resorts to laughter and satire at people's pretensions and the incongruities of existence.

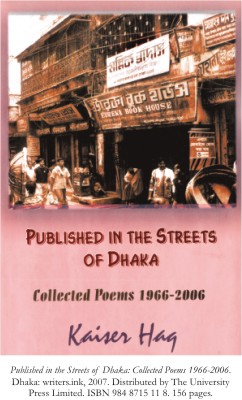

But Haq is aware, too, of how polluted the river has now become, a thought that depresses, for one is then confronted with the feeling that our "doom/looms" and all "we have/to fall back on" is "figures of speech" (and by implication, poetry!). In "Bloomsday Centenary Poem in Free Verse and Pros," written on or about June 16, 2004, he imagines Joyce's dual protagonists a century later in Dhaka "enact the Odyssean perambulations/through fetid, waterlogged lanes, /clutching dripping umbrellas/the monsoon having arrived with a bang/and tiptoeing through slush;" only, they have now metamorphosed in Haq's imagination to Ali Baba, Sindbad and Kipling's Babi Hurree Chandra Mookherjee. Almost miraculously, the poet has had "a double-barreled epiphany" of sorts that aligns him with all cosmopolitan street walkers of the imaginative kind: "Dublin is Dhaka is any city/and Bloomsday is today is any day." Haq is only too aware that, though he traverses time and space seamlessly in his imagination to become one with a poet like Rimbaud or a novelist like Joyce, writers elsewhere may not notice how much at home he is with them. The title poem of the collected poems, "Published in the Streets of Dhaka," originates in Gore Vidal's slighting reference to publishing in a city of philistines, in a characteristically acerbic passage of his essay "On Prettiness." Haq's response to the caustic American expatriate author, however, is to take up the gauntlet on behalf of his city, albeit half-seriously: he has opted to publish from where he lives, "plumb in the centre of monsoon-mad Bengal." He is only too aware that he lives in a world where things are falling apart, but he knows full well also that "evil…requires no axis/To turn on," and that Dhaka is no worse a location to pitch in together with other flaneurs of the imagination chronicling the absurdities of contemporary existence. And so he concludes that he will cut a "joyous caper" by way of a riposte to the peripatetic cynic Vidal, and in imitation of another celebrated American in self-exile, Henry Miller, "On the Tropic of Cancer, proud to be/Published once again in the streets of Dhaka." And so it is that the dust jacket of Published in the Streets of Dhaka has a sepia-tinted photograph of Banglabazar, the Grub Street of Dhaka, for Haq is truly defiant in his stance -- he is a Bangladeshi poet in English, no matter what some of his fellow citizens think about a countryman writing in English, or what the rest of the world says of the state of English-language publishing in the country. However, any reader of New Poems easily becomes aware that asserting his identity thus is, for Haq, not merely a matter of proclaiming his location in time and space but also an existential act, and even a matter of poetic affiliation. He may be writing in English, and may have T. S. Eliot, W. B. Yeats, Wilfred Owens, William Carlos Williams, the Merseyside poets and Allan Ginsburg in his poetic veins; he will also claim Rabindranath Tagore and Jibanananda Das, the two greatest Bengali poets of the last century, as his ancestors.

Haq's New Poems: 2002-2006 is thus a very confident collection of poems: this is a writer at home in his -- and the wider -- world; it is also the work of a poet at the height of his powers, and consummate in his craftsmanship. Some poems show the tight formal control of his early verse, while others meander from verse to prose (and back again!) in the calm but composed manner of his later work. At times droll and playful, on other occasions snide and frivolous, occasionally even garrulous, Haq is also capable of sounding tender, wistful, pensive, and even anguished. A poem like "Truth on the Prowl," indeed, exhibits his ability to drift tonally from moments of high seriousness to the almost pathetic within a few lines. In a number of poems he enacts a minimalist credo, while in others he seems to adopt a William Carlos Williams-like formally achieved freedom. Once in a while, a poem by Haq appears to be nothing more than a jeu d'spirit ("Snapshot"), but the collection also contains intricately structured and extended meditative poems such as "Battambang" (based on a word he has picked up from a Marguerite novel, associated with exile, rerooting and affirming life). Haq's love of the English language, fondness for word and sound play, and self-reflexive versifying is everywhere apparent in the collection ("a slippery susu in the distance/punctuates the rippling syllables -- a kinetic comma;" "the hybrid/ / interrobang;" "Ballot-box democracy is meaningless/without nomocracy," "a mathematico-metaphysical shuffle"), as is his wit and gaiety and gift for the striking image and astounding juxtapositions.

Kaiser Haq chooses to conclude Published in the Streets of Dhaka: Collected Poems 1966-2006 with an appendix that consists of a prose "Apology for Bangladeshi Poetry in English." This is a useful inclusion for it indicates why and how he chose to write poems immersed in the landscape and cityscape of Bangladesh/Dhaka in English: an English-medium education in a postcolonial country; an American missionary who showed to him in school how "writing was a process of playing with words"; the example of other sub-continental poets who opted to versify in English and showed that irony and satire if not lyric grace were attainable goals for Indians writing poetry in the language; intimacy with leading contemporary poets of Bangladesh that he has consolidated through translating them; and a commitment to unifying the sensibility of Bengalis split between a "logic-chopping" side and an emotional one. Surely, Haq's volume of collected poems is a testament to a major Bangladeshi poet writing in English who deserves to be much better known now not only in his own county but in the wider world. Fakrul Alam is Professor of English at the University of Dhaka. His most recent work is South Asian Writers in English, a volume in the Dictionary of Literary Biography series. Drowning is the greatest danger for small children in Bangladesh The biggest killer of children aged one to four in Bangladesh is drowning, according to newly published data by ICDDR,B. The current figures show that up to 17,000 Bangladeshi children die of drowning a year -- on average, 46 children a day. The recently conducted Bangladesh Health and Injury Survey (BHIS) found that injuries of all kinds are the biggest killer of Bangladeshi children under eighteen today, with an estimated 30,000 deaths every year caused by childhood injuries.

Over the past decade, ICDDR,B has found that most drownings actually occur in ponds or ditches, in the monsoon season, in children between one and two years of age, and between 9 am and noon when the mother is busy with household work. The current BHIS data also shows that more than 75 per cent of drownings take place in bodies of water less than 20 metres from the house, with children unable to or too young to know how to swim. Great progress in reducing child mortality from infectious diseases in Bangladesh during the last two decades has meant that injuries and accidents, such as drowning, are now emerging as a greater threat to child survival. But as this has yet to be recognised widely, there are no parental awareness raising campaigns, no programs teaching adults how to respond to life-threatening accidents and injuries. However, ongoing research by ICDDR,B and Johns Hopkins University is being conducted to develop and test ways of preventing children from drowning in rural Bangladesh. - Forum Desk

|

T

T Again and again, the new poems have Haq oscillating serio-comically between the unreal and exhausting nature of life in Bangladesh, where everyday he encounters "the murderous decibels /of hucksters, honkers, sloganeers" (Spend, Spending, Spent), and the solace he finds in the company of great artists, seekers and thinkers with whom he feels akin in his search for a way out of a "passing show" that is perpetually tinged with the absurd. "Figures of Speech," the second poem of the New Poems section of the volume, thus begins with the poet ruminating on childhood memories of bathing in the river of his ancestral village, which make him remember Heraclites on flux, Buddha on time and being, Rimbaud on the self and the other.

Again and again, the new poems have Haq oscillating serio-comically between the unreal and exhausting nature of life in Bangladesh, where everyday he encounters "the murderous decibels /of hucksters, honkers, sloganeers" (Spend, Spending, Spent), and the solace he finds in the company of great artists, seekers and thinkers with whom he feels akin in his search for a way out of a "passing show" that is perpetually tinged with the absurd. "Figures of Speech," the second poem of the New Poems section of the volume, thus begins with the poet ruminating on childhood memories of bathing in the river of his ancestral village, which make him remember Heraclites on flux, Buddha on time and being, Rimbaud on the self and the other.  To Tagore, therefore, he pays ambivalent homage in "Lord of a Dark Sun." Haq is certainly snide in this poem about aspects of Tagore's work and his "perennial philosophy," but his penchant for play and parody, his preference for "celestial chiaroscuro," his "tormented" brush strokes, and incisive words make Haq pay his respects to one who has been "an exemplar/for our entropic millennium, /Lord of the Sun,/Lord of the Dark Sun." Das merits from Haq a full-length affectionate parody: the Bengali poet's most famous creation, Banalata Sen, is now reincarnated as "ms bunny sen," for when Haq is "absobloodylutely/knackered," he hints, he can't help seeking out the company of Das and opt for a "tête-à-tête/with ms bunny sen of Banglamotor." In "Published in the Streets of Dhaka," moreover, Haq places himself intertextually in Das's Bengal, as he watches "Jackfruit leaves drift earthward/In the early morning breeze" as did this famous predecessor in the lovely sonnet on reincarnating in one's homeland , "Abar Ashibo Phire" ("I'll come back again"). Also, in "A to Z, Azad," a poem written after Humayan Azad, a major Bangladeshi poet and novelist who died not long ago, soon after he was attacked brutally by fundamentalists in Dhaka, Haq registers his solidarity with writers who are audacious enough to speak out (the Bengali poet's surname means "to be free"), and affirms his kinship with writers everywhere who use poetry to protest against tyranny and the forces of evil.

To Tagore, therefore, he pays ambivalent homage in "Lord of a Dark Sun." Haq is certainly snide in this poem about aspects of Tagore's work and his "perennial philosophy," but his penchant for play and parody, his preference for "celestial chiaroscuro," his "tormented" brush strokes, and incisive words make Haq pay his respects to one who has been "an exemplar/for our entropic millennium, /Lord of the Sun,/Lord of the Dark Sun." Das merits from Haq a full-length affectionate parody: the Bengali poet's most famous creation, Banalata Sen, is now reincarnated as "ms bunny sen," for when Haq is "absobloodylutely/knackered," he hints, he can't help seeking out the company of Das and opt for a "tête-à-tête/with ms bunny sen of Banglamotor." In "Published in the Streets of Dhaka," moreover, Haq places himself intertextually in Das's Bengal, as he watches "Jackfruit leaves drift earthward/In the early morning breeze" as did this famous predecessor in the lovely sonnet on reincarnating in one's homeland , "Abar Ashibo Phire" ("I'll come back again"). Also, in "A to Z, Azad," a poem written after Humayan Azad, a major Bangladeshi poet and novelist who died not long ago, soon after he was attacked brutally by fundamentalists in Dhaka, Haq registers his solidarity with writers who are audacious enough to speak out (the Bengali poet's surname means "to be free"), and affirms his kinship with writers everywhere who use poetry to protest against tyranny and the forces of evil.  Because Haq has chosen to begin his Published in the Streets of Dhaka 1966-2006 with New Poems: 2006-2006, it is easy for the reader to see that he intends to make us view this latest collection of verse as the climax of a long and fruitful career. It also allows us to note that he has never been prolific -- and how could he be so? He has too fastidious a sensibility -- he has always been aiming for excellence and cultivating a rooted kind of cosmopolitanism from the beginning of his career, so that he could affiliate himself with international literature while representing his own corner of the world. After New Poems, Haq reverts to the chronological format standard in most volumes of collected poems. As a result, one can view his progress from the Kiplingesque "Les Miserables" (published when he was still in school) to the zany poems written either under the influence of the pop poetry of the sixties, or because of his preference at one stage of his career for the ironic but urbane English poets of the nineteen fifties and the sixties. One can also glimpse other phases of his poetic development, for instance the time when he had a fondness for hilarious Nissim Ezekiel-like poems in "subcontinental English," or when he began to savour the freedom of vers libre. Here it may be noted that while he appears to have enjoyed writing in free verse even in his early poems, he appeared to have taken to it most when he let Eros lead him away from almost all formal restraints in the poems of the Black Orchid volume.

Because Haq has chosen to begin his Published in the Streets of Dhaka 1966-2006 with New Poems: 2006-2006, it is easy for the reader to see that he intends to make us view this latest collection of verse as the climax of a long and fruitful career. It also allows us to note that he has never been prolific -- and how could he be so? He has too fastidious a sensibility -- he has always been aiming for excellence and cultivating a rooted kind of cosmopolitanism from the beginning of his career, so that he could affiliate himself with international literature while representing his own corner of the world. After New Poems, Haq reverts to the chronological format standard in most volumes of collected poems. As a result, one can view his progress from the Kiplingesque "Les Miserables" (published when he was still in school) to the zany poems written either under the influence of the pop poetry of the sixties, or because of his preference at one stage of his career for the ironic but urbane English poets of the nineteen fifties and the sixties. One can also glimpse other phases of his poetic development, for instance the time when he had a fondness for hilarious Nissim Ezekiel-like poems in "subcontinental English," or when he began to savour the freedom of vers libre. Here it may be noted that while he appears to have enjoyed writing in free verse even in his early poems, he appeared to have taken to it most when he let Eros lead him away from almost all formal restraints in the poems of the Black Orchid volume. However, in a country with the world's highest density of rivers, and approximately two-thirds of the land frequently flooded, the greatest danger comes from drowning. Although rates of drowning have remained stable since the 1980s, drowning as a proportion of all deaths in children aged one to four has increased from nine per cent in 1983 to 59 per cent in 2003.

However, in a country with the world's highest density of rivers, and approximately two-thirds of the land frequently flooded, the greatest danger comes from drowning. Although rates of drowning have remained stable since the 1980s, drowning as a proportion of all deaths in children aged one to four has increased from nine per cent in 1983 to 59 per cent in 2003.