Inside

|

Ensuring the people's right to know Sadrul Hasan Mazumder makes the case for ending the state's media monopoly

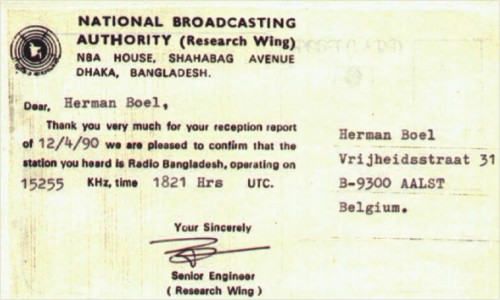

If such national assets were to become the mouthpiece of any one, or combination of, the parties vying for power, democracy would be no more than a sham. An important implication of these guarantees is that bodies which exercise regulatory or other powers over broadcasters, such as broadcast authorities or boards of public broadcasters, must be independent. Background The functions of the National Broadcasting Authority (NBA), which was formed on May 24, 1986 following President's Ordinance amongst others, were to control, manage, operate, and develop the radio and television media of Bangladesh, and to implement the policy of the government with respect to their broadcasts. As per provision of the Ordinance, no plans and programs could be implemented by the NBA without prior clearance from the government. The said Authority, in the discharge of its functions, was bound by such general or special instructions as issued by the government from time to time. Mass media as means of governance In any democracy, access to the media is one of the key measures of power and equality. The media can shape power and participation in society in negative ways, by obscuring the motives and interests behind political decisions, or in positive ways, by promoting the involvement of people in those decisions. In this respect the media and governance equation becomes important. In a democratic society, the role of the media assumes seminal importance. Democracy implies participative governance, and it is the media that informs people about various problems of society, which makes those wielding power on their behalf answerable to them. That the actions of the government and the state, and the efforts of competing parties and interests to exercise political power, should be underpinned and legitimized by critical scrutiny and informed debate facilitated by the institutions of the media is the assumption uniting the political spectrum. Guaranteeing people's right to know The public broadcasting sector in Bangladesh has been misused as a propaganda tool of vested interests of the party in power. Bangladesh Radio and Bangladesh Television were established with the primary aim of rendering public service by the transmission of news and entertainment. But both institutions were, from their very inception, devalued by political appropriation, overt censorship and restraints. During the recent political turmoil the private-owned electronic media played an important role, but people at large found the public media BTV and Bangladesh Betar as grass-roots voices During the political government rule, radio and television seemed to the people to be "His Master's Voice" a totally mysterious thing. And the audience fell victim to their captivating allure. Radio stations gave birth to a sort of master-servant relationship in which the anchorman symbolizes a lord, and the audience his obedient servants. Since different means of mass communication couldn't get out of the ideological straitjacket of traditional ideas, they have failed to reflect the uniform, mass-oriented pattern of life. But the truth of the matter is that planners and executives in the past were far from regarding mass media as the key to the development process, and imposed an undemocratic and unconstitutional decree upon the public. Consequently, the right of the common people to have access to information, which constitutes the mainstream of development, suffered a serious setback. The way the previous government delayed in making BTV and Bangladesh Betar real autonomous institutions exposed its dictatorial approach to the information system. The problems of the common people, and their thoughts and ideas, should be reflected in the state owned media, which is basically run with the tax money they pay. Politics of autonomy Until 1991, the issue of autonomy of radio-TV did not come to the forefront of the societal discourse. Granting autonomy to Radio and Television was one of the main points in the joint declaration of the three alliances, announced after the fall of Ershad. On November 19, 1990, the three major political alliances gave a joint declaration to consolidate the movement against autocracy. Section 2(d) of the joint declaration states: "The mass media, including the radio and television, will have to be made into independent and autonomous bodies so that they become completely neutral." After the democratic election, and with the restoration of parliamentary democracy in 1991 on the basis of consensus among major political parties, the issue of public broadcasting autonomy gained momentum. It was a great expectation of the general people involved in the anti-autocratic movement that autonomy of the electronic media would be granted, in line with the joint declaration. But we noticed with frustration that the BNP government did not uphold its commitment to grant autonomy to the electronic media during its tenure (1991-1996). The then minister for information publicly denounced the idea of neutrality of state-run media, and claimed the government's right to enjoy subjective coverage. Such an absolutely unprecedented argument in favour of a "loyal electronic media" from an elected government put an abrupt end to the hope for an autonomous public broadcasting service. However, the BNP government did form a commission to assess the matter. The commission prepared a set of recommendations to relax government control over the electronic media. But the recommendations were never published, let alone materialized. Left Democratic Front leader, Rashed Khan Menon, moved a resolution seeking withdrawal of state control over the public broadcasting in the fifth parliament, where he proposed that the authority of the parliamentary committee on the ministry of information be strengthened to conduct the affairs of Betar-BTV. But the resolution was not passed. The Awami League government constituted a 16-member "Commission for Framing Rules and Regulations for the Autonomy of Bangladesh Television (Radio-TV Autonomy Commission)" in September 1996. Report at a glance Status of implementation Political commitments During the June 12, 1996, general election, Bangladesh Awami League promised "Autonomy to radio, TV and government-controlled news media. Privatisation of newspapers now owned by the government," while Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) promised that the policy for free flow of information would continue.

End notes Sadrul Hasan Mazumder is a development activist. |

|

T

T behaving like in the past.

behaving like in the past.