Inside

|

The third decade of Saarc Sridhar K. Khatri assesses where things stand and what needs to be done

In the wake of the 14th Saarc Summit in New Delhi there is no dearth of vision on how Saarc should proceed in achieving meaningful cooperation in the region. But there is lack of clarity on how the strategy should be implemented. There have been many inputs from civil society on what steps need to be taken, but the absorption capacity of inter-governmental institutions has been limited in this regard. Even the seminal Report of the Saarc Group of Eminent Persons (GEP), established by the Saarc Summit in 1997 at Male, was not fully discussed at the inter-governmental level nor endorsed in its entirety. But subsequent summits have taken in many of the recommendations of the GEP without establishing adequate mechanisms to monitor their implementation. These include the commitment of Saarc to the following goals: Although valid criticisms can be made about Saarc not producing any concrete result to which the people of the region can relate, there has, nevertheless, been significant progress in a number of areas. *Similar progress has been made regarding poverty alleviation in the region, despite the unrealistic deadline set to "eradicate" poverty in South Asia by 2002. The reconstituted Independent South Asia Commission on Poverty Alleviation (ISCAPA) has adopted a more reasonable approach by suggesting a 24-point approach for halving poverty in South Asia by 2010, as opposed to MDG of the UNDP that requires South Asia to do so by 2015. *The establishment of South Asia University seems to be off to a promising start, where the inter-governmental committee of experts has already approved the draft prepared by Dr. Gowher Rizvi, and is likely to be endorsed by the summit in New Delhi. The novel recommendation of the report is that the university might materialize as a joint public and private sector enterprise which could be operated relatively free of governmental controls. *After years of discussion, and, to some extent, a large degree of negligence, the South Asian Development Fund is also making some headway, with assets amounting to around $300,000,000. *The Saarc Secretariat has also prepared a comprehensive report with the assistance of ADB in developing a multi-modal transport system in the region. As many of you will agree, the main obstacle to realizing the connectivity of South Asia is political. But even on issues that were considered to be sensitive, we are today seeing greater flexibility. The "composite dialogue" between India and Pakistan over the past two years has led to opening of bus and railway services, and dialogue over strategic issues on Siachen, Sir Creek and the future of divided Kashmir. The Indo-Pakistan dialogue has had a salutary affect on regional cooperation, where both India and Pakistan are willing to consider key areas of cooperation more openly than before. Moreover, there is also a newly found confidence in the region, which is in large part reflected by the surprisingly high growth rates in India and Pakistan. Given Saarc's checkered history over the past two decades, there is no denying that in the coming years Saarc is likely to muddle through as it has done in the past, without making any significant dent on the lives of its people or in the political economy of the region. But there are positive indications that South Asia will begin to exhibit its dynamic character in the future, despite itself and the inhibitions it has demonstrated over the past two decades. This optimism regarding the region's future is not based on the belief that governments will one day realize their tardiness and then turn around and take some serious measures to bring South Asia into the mainstream of the international development process. It is based rather on the belief that, despite the failures of governments, there are positive trends which indicate that South Asia is on a positive trajectory for greater cooperation, which governments will be forced to follow in the years to come. Let me just cite a number of examples to support this argument. First is the case of poverty in South Asia. Looking at the two different periods, 1981 and 2001, there has been a marked improvement where the proportion of the extreme poor has gone down from 52 percent to 31 percent. Although this is not as significant as it was in East Asia, where the proportion plummeted from 58 percent to 15 percent, it is nevertheless a significant achievement for the region. The second case is that of economic growth, which has been exemplified by India since it began its liberalization programs in the 1990s. India is now the world's fourth largest economic power, and many expect it to surpass Japan to become the third largest very soon. The entrepreneurs, especially in the IT sector, are the catalyst in India's economic miracle, and have managed to fuel growth through the service sector and domestic consumption. India has managed to maintain an average of 7.5 percent growth rate for the past five years, despite archaic labour laws and "bureaucratic high modernism." India is not alone in registering a positive growth trend in the region. Roberto Zagha did a study in 2005 which lists as "growth successes" those countries with a faster per capita GDP growth rate than the US in the 1990s, and a 1980s growth rate of at least 1 percent. His list contains one Latin American country (Chile), a couple of small African countries (Botswana, Lesotho), no Eastern European or Central Asian country, but six of the eight South Asian countries. Shantayanan Devarajan of the World Bank argues that although some of the same phenomena are present to some degree in South Asia, there has nevertheless been a turn for the better in the region due to a number of exceptional factors: *The case of Sri Lanka and Nepal illustrates that although internal conflicts can be extremely debilitating for countries, and can hold back their potential, the future prospects need not always be dim for nations caught in the conflict trap. Despite two decades of conflict, Sri Lanka grew at over 3 percent per year. The Sri Lankan example proves that there can be growth in non-conflict areas of the country when the conflict is localized. *On the other hand, in Nepal, at the height of the Maoist insurgency (1996-2004), per capita private consumption grew at over 4 percent a year, or 40 percent over the eight-year period. The dramatic reduction in poverty was made possible by substantial remittances coming into the country from the Middle East and India. *As for the natural resource curse, the Maldives has averaged 9 percent GDP growth over the past two decades, with per capita GDP of $2,300. The growth has come primarily through the tourism industry. *Bhutan has a fixed exchange rate with India, but its economy has been growing at 6.6 percent, with per capita GDP growing at 4.4 percent. The contribution of India (and one can add also China) as an engine of growth for South Asia will be substantial, since it accounts for (in 2005) about 80 percent of South Asia's GDP, trade, and regional growth. In South Asia, India's development into a regional hub would attract more foreign direct investments into India, and from India to other South Asian countries, which would boost economic growth in the whole region. As the latest ADB report states: "India is not only crucial for the success of regional trade cooperation in South Asia; it could also transform the development and growth pattern of the entire region." The latest report by the World Bank, entitled Global Economic Prospects: Managing the Next Wave of Globalization, is even more upbeat. It predicts that in the next 25 years the growth in the global economy will be powered by the developing countries, whose share in global output will increase from about one-fifth of the global economy to nearly one-third. It means that some of the key drivers in the global economy will be China and some of the countries from South Asia. There are today six developing countries which have populations greater than 100 million and GDP of more than $100 billion. By 2030, there will be 10 countries that would have reached the twin 100s threshold, and four of them will be from the vicinity of South Asia. In addition to India and China, who have already reached that level, Pakistan and Bangladesh are also likely to be part of this dynamic group.

The question is: Will the approach adopted by India and China be applicable to India's relations with Pakistan? My impression is that, in time, anything is possible. If two rivals such as India and China can put their territorial differences aside to achieve major economic gains, it is also possible for India and Pakistan to find ways and means to benefit economically without sacrificing their stands on political and territorial issues. The important thing is for Pakistan to overcome its fear that open trading arrangements with India, bilaterally or multilaterally, will not lead to Indian products swamping its market at the cost of its own industries. For its part, India needs to be confident of its growing economic power to be able to devise ways to placate the Pakistani fears, both real and imagined. A fourth major catalyst for deeper integration in South Asia could come from a force whose potential has largely gone unrecognized today. It is possible that we may see the private sectors and civil society playing a more decisive role in regional cooperation in the years to come. During the last 10 years, it has been the practice to include a representative of the private sector in the official delegations of governments during crucial trade negotiations. The role played by various business groups in framing the bilateral free trade agreements between India and Sri Lanka, and between Sri Lanka and Pakistan, was substantial, as it was in the case of India's bilateral trade agreements with Nepal and Bangladesh. It may only be a matter of time before the private sectors in the region begin to define for member countries of Saarc the economic benefits of cooperation, instead of being led by the bureaucratic elite. Similarly, the advent of Saarc has generated a sense of regional consciousness among the peoples of the region in the last two decades, something which has never been seen before. The interaction among civil society groups across South Asia, and the non-official dialogues they initiated and maintained through the Track II process, have made it possible to examine issues which governments have been reluctant to explore on their own. Over the years, they have been able to: It is most likely that in the next decade initiatives like the Pakistan-India Peoples' Forum for Peace and Democracy, which aspires to facilitate interaction among the common people in both the countries, will no longer remain a background voice, but act as catalyst for change in the way their countries deal with each other. Moreover, the new technotronic era is likely to have effects that we may not be able to appreciate at the moment. The impact of the electronic and print media in the region will be to bring people and countries closer together. As the World Bank's Global Economic Prospect report for 2006 shows, the competitiveness in the global market is not limited to white collar jobs only. South Asia receives around $32 billion annually in remittances, by exporting labour to the Gulf region and the East and Southeast Asian countries. In Pakistan, remittance increased four-fold, from just over $1 billion in 2001 to over $4 billion in 2003; in Bangladesh, it increased from $1.9 to $3.3 billion; in India, it increased from $12 to $21.7 billion, and Nepal receives $1.5 billion. The remittances account for a high percentage of foreign currency earned by many of the smaller countries in the region. My point is very simple. In the age of New Regionalism that is technology and competition driven, it is not enough for South Asia, or for that matter potential partners of Saarc (like China, US, Japan and Korea), to think small, as we have done in the past. What is needed for cooperation within Saarc, and between its potential partners, are investments that would emulate the Fukuda Fund for Asean, which was nothing short of $1 billion needed to develop important infrastructures. In the case of South Asia, investment is badly needed for energy, transport networks, and major industrial projects which provide a boost to free trade, both within and between our regions. Despite the slow progress of Saarc as an institution, there are indications that South Asia is already beginning to think big about itself as a region. The proposal to set up a South Asian University is the best example, since it would require nothing short of $1 billion to do so. The business community is thinking even further ahead of the governments in the region. In anticipation of Safta, the Tata group of India has already proposed a $3 billion investment in Bangladesh in gas-based fertilizer, power and steel plants. If South Asia is to move forward at a pace that the people of the region wish to see, the vision and strategy for the third decade must include a certain degree of commitment to achieve the goals that we have become familiar with over the years. This entails not only defining new goals for the years ahead, but also strengthening institutions like the Saarc Secretariat, and devising mechanisms which will monitor its implementations within specified timeframes. This alone could be the greatest goal Saarc could set for the third decade, since it would make no sense to have programs without the mechanisms to implement them. If Saarc is to reflect in some form the meaning of a resurgent South Asia, it must prioritize its ambiguous agenda. There are many issues that can be included in the recommendations, but a few of these are spelt out below: 1. Safta and Beyond: Safta is a major achievement for Saarc. However, a recent study for South Asia Centre for Policy Studies (Saceps) underscores that tariff liberalization for enhancing trade flow is not enough. Until non-tariff barriers come down there would be major limitations on the Safta process. There would also be significant limitation on trade, unless Safta's scope includes the service sector and adequate attention is paid for forging linkages between investment and trade. Intra-regional investment flows are needed to overcome the existence of limited export supply capabilities of some of the countries of the region. In addition, the full benefits of trade can only be enjoyed after certain infrastructure, like energy and transport, are fully developed in the region. As the ADB report on Saarc Regional Multimodal Transport System has emphasized, many of the "building blocks" for a more efficient system are already in place. Saarc can help to create the environment where these blocks can be combined to support an efficient regional transport system.

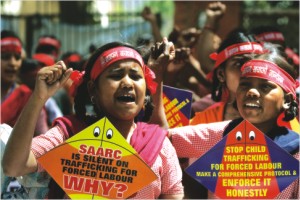

2. Capacity of Saarc to absorb and implement ideas: The capacity of Saarc member governments and its institutions to digest concrete recommendations from various civil society groups, and those commissioned by the governments themselves, needs to be strengthened. For instance, the GEP Report which was mandated by the Male Summit in 1997 never received appropriate attention. If a lesson is to be drawn from the GEP Report, it is simply that Saarc has yet to develop an institutional mechanism to absorb ideas that reach the governments, let alone implement them. Three former Saarc secretaries general and the author recommended in an article some time ago that Saarc might consider setting up an advisory committee of experts selected by member governments to provide independent feedback to the council of ministers on salient programs and policy which might need priority consideration. This option is still a viable one today. 3. Institutional mechanisms: Saarc's institutional mechanisms, in particular the Secretariat, need to be made more professional to meet the requirements that naturally flow from greater integration in the region. A recent study conducted by Saceps on policies and programs of Saarc gives a dismal report on the performance of the organizations in the past two decades.2 Despite the good intentions of Saarc Summits, and the declarations that come out afterwards, many commitments by governments go unfulfilled. Food security reserves have never been used, even during times of crises, and there are no delivery systems in place for it to be viable during times of need. The convention on terrorism exits only on paper, since there are no national enabling mechanisms in place or bilateral extradition treaties that can give it meaning. There has also been no action taken to control abuse of drugs and psychotropic substances, nor has there been serious regional follow-up on trafficking of women or promotion of child welfare. Even NGOs working on these issues have been marginalized, or obstacles have been created in their functioning. In the last few years, the organization has called for an official review of Saarc Integrated Program of Action (SIPA), but there are no independent reviews of the work aside from the work undertaken by Saceps recently. The common problems identified by the study include: lack of coordination of activities; non-participation in meetings; lack of resources to implement programmes; lack of sectoral cooperation; and non-implementation of decisions. 4. The peoples of South Asia: An essential ingredient for a vision of South Asia for the Third Decade is the people of the region. As one of the participants in a FES conference on Saarc, in New Delhi, put it very eloquently: "Saarc needs to be brought to the level of the people, since what the masses feel will count for the government." The flaw in the present Saarc process is that although the governments in theory represent the people, no questions have been raised as to how far they have remained accountable in achieving the objectives of the organizations. There are many civil society groups that have been active in raising some fundamental issues before the Saarc governments, but their voices have had minimal impact since Saarc has failed to develop a strong constituency, which is essential if any body politic is to get anything done. One of the major achievements of Saarc in this context is the Saarc Social Charter, and the supplementary Citizen's Social Charter formulated by Saceps, which makes government accountable for economic and social welfare of the people of the region. The Social Charter is the first document of its nature, where citizens have a right under an international agreement to monitor the progress made by governments in their respective countries. A preliminary work done by Saceps in monitoring the Social Charter in five South Asian countries has not been promising, since many countries have yet to examine and set up mechanisms to implement their obligations.

1. Navnita Chadha Behera, Paul, M. Evens and Gowher Rizvi, Beyond Boundaries: A Report on the state of Non-Official Dialogues on Peace, Security and Cooperation in South Asia (North York, Ontario: University of Toronto-York University, 1997), pp. 28-31. 2. Mahendra P. Lama, SAARC Programmes and Activities: Assessment, Monitoring and Evaluation, SACEPS Policy Study No. 14. (forthcoming) Sridhar K. Khatri is Executive Director, South Asia Centre for Policy Studies. The above was presented at a seminar on "Saarc: Vision for the Future" organized by the Institute of Foreign Affairs, Kathmandu. Photos: AFP |

International as the most corrupt country in the world, Bangladesh is growing at 5 percent a year, with per capita GDP growing at over 3 percent. The country has made significant progress in human resource development, and is on track for reaching the Millennium Development Goal of reducing poverty by two-thirds by 2015. The reason for Bangladesh's positive growth rate goes beyond conventional economics since people have not only "found ways of going around the government" but also because "the government made space for NGOs and the private sector to function." There is a parallel economy for service delivery in the education and health sectors that has been financed by the government or by donors, but it is not the government officials who are running the system. And Bangladesh's world famous micro-credit industry now has 14 million clients, mostly women, and operates almost entirely outside the public sector.

International as the most corrupt country in the world, Bangladesh is growing at 5 percent a year, with per capita GDP growing at over 3 percent. The country has made significant progress in human resource development, and is on track for reaching the Millennium Development Goal of reducing poverty by two-thirds by 2015. The reason for Bangladesh's positive growth rate goes beyond conventional economics since people have not only "found ways of going around the government" but also because "the government made space for NGOs and the private sector to function." There is a parallel economy for service delivery in the education and health sectors that has been financed by the government or by donors, but it is not the government officials who are running the system. And Bangladesh's world famous micro-credit industry now has 14 million clients, mostly women, and operates almost entirely outside the public sector. Taking the economic argument one step further, it is possible to envision a third case where economic compulsion in the region may eventually help to bring down the political barriers, particularly between India and Pakistan, in South Asia. The best examples are India and China, where the two countries after fighting a war in 1962, have, without resolving their territorial differences, engaged each other since the late 1980s. As a result, bilateral trade has boomed from less than $200 million in the early 1990s to nearly $20 billion in 2005. China is set to overtake the EU and the US as India's largest trading partner within a few years. And, despite some political and territorial differences, both countries agreed to set up a "strategic partnership" in April 2005, which has led to frequent high-level visits by leaders to each others' capitals.

Taking the economic argument one step further, it is possible to envision a third case where economic compulsion in the region may eventually help to bring down the political barriers, particularly between India and Pakistan, in South Asia. The best examples are India and China, where the two countries after fighting a war in 1962, have, without resolving their territorial differences, engaged each other since the late 1980s. As a result, bilateral trade has boomed from less than $200 million in the early 1990s to nearly $20 billion in 2005. China is set to overtake the EU and the US as India's largest trading partner within a few years. And, despite some political and territorial differences, both countries agreed to set up a "strategic partnership" in April 2005, which has led to frequent high-level visits by leaders to each others' capitals.

5. Open dialogue: An excellent paper prepared by a retired Indian diplomat and a former secretary in the External Affairs Ministry has called for some "fresh," if not radical measures, for improving the lives of the people of this region. He argues that if Saarc has not achieved its objective then "it is time to consider improving it, or even [consider] an alternate and workable model of regional cooperation…" even if it means "reformulating" the Saarc Charter to bring it in line with people's aspirations in the context of South Asian resurgence and globalization. He says that if we can dream of a South Asian Economic Union then future steps might include discussion on security and foreign policy issues, free movement of people, and even setting up a South Asian Regional Forum on the ASEAN-ARF line. Our newly found confidence in South Asian resurgence will have little meaning without the ability to explore all possible options.

5. Open dialogue: An excellent paper prepared by a retired Indian diplomat and a former secretary in the External Affairs Ministry has called for some "fresh," if not radical measures, for improving the lives of the people of this region. He argues that if Saarc has not achieved its objective then "it is time to consider improving it, or even [consider] an alternate and workable model of regional cooperation…" even if it means "reformulating" the Saarc Charter to bring it in line with people's aspirations in the context of South Asian resurgence and globalization. He says that if we can dream of a South Asian Economic Union then future steps might include discussion on security and foreign policy issues, free movement of people, and even setting up a South Asian Regional Forum on the ASEAN-ARF line. Our newly found confidence in South Asian resurgence will have little meaning without the ability to explore all possible options.