Inside

|

Harvesting for Health Niaz Ahmed Khan and A.Z.M. Manzoor Rashid scrutinise the uses of indigenous medical plants in the Chittagong Hill tracts It has lately been unequivocally established that medicinal plants and associated knowledge, which represent a part of rich local heritage, play a significant role in the general welfare of the upland communities of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Notwithstanding the recognition and emphasis, however, organised research and information on indigenous medicinal plants and knowledge have been strikingly limited. In recent years, a general concern has been that this local wisdom is fast eroding for reasons such as biotic interference, shrinking land resource base, deforestation, insufficient support from the government and public policies, and lack of appropriate management and institutional structure.

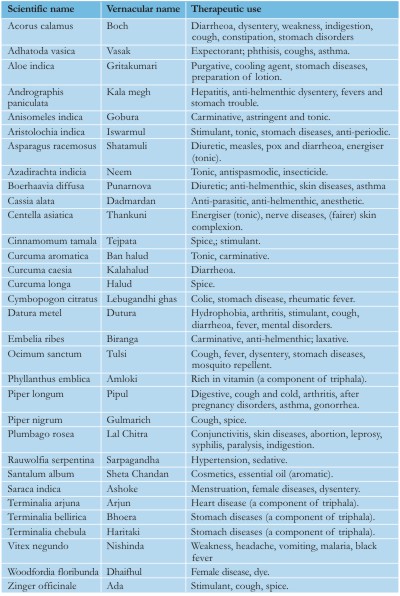

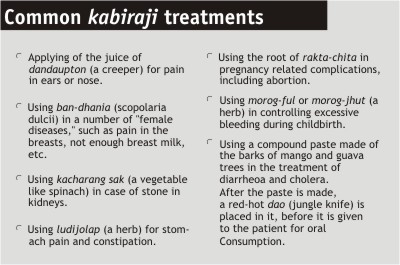

This article, drawing on empirical fieldwork, sheds some light on the indigenous medicinal plants and associated knowledge and practices in six locations in CHT -- Lama, Sualok, Balaghata, Chemidolupara, Majherpara, Madhapara, under the district of Bandarban. The following is a table of important plants which have been observed in the study areas. These plants are preferred as the baidyas (gypsies) because of: (a) their adaptability to the edaphic and climatic conditions of the locality, (b) their market potential, and (c) the diverse use of many of them in different medicines as the "base" ingredient. List of the Major Medicinal and Spice Plants Commonly Observed in the Study Areas Medicinal plants are often found along hedges and boundary lines. The shrubby species are usually cultivated as undergrowth in homestead plantation areas and also in the fallow lands. Organised commercial plantations (as distinct from irregular homestead plantations) are virtually absent. Scientific silvi-cultural practices (e.g. weeding, pruning) are not usually followed. Women play a major role in maintaining the (limited number of) homestead medicinal plantations in the locality. A number of baidyas from the Marma community possess written manuals (Burmese scripts) on the practice, and they deal more in mainstream herbal treatment compared to the tantra-montro or spiritual and sacred ceremonies. The baidyas representing the Tanchangya community are more into the practice of tantra-montro. Glimpses of the life and living of a baidya Shashi represents the Tanchangya tribe. As a baidya, he needs to perform a twofold role: treatment with herbal medicine (kabiraji), and spiritual healing (ban-tona). The raw materials or crude drugs needed for kabiraji had traditionally been available locally. However, now, you do not find trees and herbs in the local jungles. The rocks are barren. People cut trees and take them away in trucks. If you cut trees, herbs also die; trees and herbs are like brothers. One cannot live without the other. Various types of kabiraji treatments are outlined in the accompanying box. Not much is known to us about the other world of ban-tona (spiritual healing). Shashi explains: "You learn this [practice] from your fathers and grandfathers... You have to love and adore the spirits, [until] the spirits gets into you [and starts] living in your [soul]. I learnt it from my father Chandra baidya, who was taught by his father. It took 20 years for my father to learn the montro [the sacred words] and he became the personal baidya of an official of the King …" We saw about 25 dried gourds, arranged in two rows, in Shashi's house (we were invited to his house for a short while towards the end of our discussion). The usual practice is to utter the montro into the gourds and then give each montro-charged gourd to the patient or devotee for consumption. Sometimes, other small objects, known as tabiz, are also offered as talismans. People come to the baidya with a range of problems and complications ranging from troubles with love affairs, litigation issues, crop failure; natural calamities, how to win over enemies, how to influence other people's lives and minds, and treatment for sexual disorders or desires. Some even want to predict the future. The knowledge and wisdom which underpin the practice of baidyas are mostly passed on from one generation to the other. Baidyas provide two broad categories of services: plant-based (curative and preventive) treatment and healing (kabiraji); and spiritual and sacred ceremonies (tontra-montro). Nine out of 30 baidyas maintain a reasonable stock of the major medicinal plants and herbs in and around their homes. Family members, especially the women, typically look after these plantations. Only three respondents have a special chamber for attending to the patients. Others do not have any special provision or formal arrangement, except for small wooden boxes to store the basic equipment and raw materials for the practice. Most <>baidyas<> collect raw materials from local bazaars. For more widely used materials, they occasionally approach intermediate agents or city-based wholesalers. There are a few medicine shops in Chittagong which deal in herbal and medicinal plants. It is difficult to determine a baidya's income. Their income varies substantially, and shows seasonal fluctuations (e.g. winter is often a busy time for the baidyas in handling cases of mental disorder, high monsoon for water-borne diseases). A good number of respondents expressed their unwillingness to talk about their earnings. Besides, for nearly two-thirds of the baidyas, the practice is not the only source of livelihood. They typically rely on other sources of income such as small businesses, collection of non-timber forest products (bamboo, fuel-wood, sun-grass, honey, etc), livestock rearing, sharecropping, and wage labour. The lowest and highest incomes from the practice of baidya, as reported by the respondents (who agreed to share the information), are Tk 1,400 and Tk 6,000. Drawing the respondents' comments and responses, major problems and challenges concerning the practice of baidya arose. The most widely used species in the preparation and practice of medicine are becoming increasingly rare and difficult to procure because of rapid destruction of the natural forests (mainly prompted by organised illicit commercial logging), bureaucratic complications and harassment (e.g. by the Forest Department), inaccessibility, and difficulties in communication and transportation. Also, there is no formal arrangement or institution in the locality to train and nurture this knowledge. Institutional mechanisms for dissemination or extension of the knowledge and practice are also absent. The time of collection and harvesting of medicinal plants is a vital factor in ensuring efficacy of the medicines prepared thereof. The time factor is often ignored or by-passed by the baidyas due to acute shortage of, and great demand for, these plants. Local people nowadays prefer modern mainstream treatment. The reduced number of patients, coupled with the difficulty in obtaining raw materials, makes the practice of baidya almost unsustainable. Unfortunately, the young generation does not show much interest in learning the traditional practice., believing that the profession lacks promise for all the difficulties previously explained. While the majority of existing baidyas buy the raw material (spices, plants, stamp, seeds, roots etc.) of their practice from the local markets, many said that these materials were generally of low quality and poor stock. To ensure a sustained source of quality seeds and seedlings, a central propagation nursery is badly needed. There is also almost no institutional and external support and patronisation, especially from the government, because the development and promotion of indigenous medicinal plants and knowledge are nearly absent in the study areas.

Drawing on the respondents' comments and our observation during the fieldwork, we have drawn up the following ideas on how the baidya's life and trade could be protected and improved: -With the active participation of the local people, the existing medicinal plants should be systematically documented and recorded. -Organised motivational and awareness raising campaigns regarding medicinal plants and their benefits (e.g. free from negative side effects, low cost) may be carried out at the community level, especially amongst the younger population, by involving the community leaders and local community based organisations (e.g. schools and religious institutions) and NGOs. -Experimental propagation nurseries may be established under government and non-government initiatives to ensure sustained supply of seedlings. -Mainstream research institutions in the country, especially the forest and agricultural research institutes and universities, may be encouraged to provide the much-needed research support for proper documentation and dissemination of the knowledge on medicinal plants and associated folk and herbal treatment methods. -The local press, media and folk cultural practices (e.g. folk theatres) may be utilised as community-based extension and dissemination media to highlight the importance of conserving this traditional practice and heritage. -Local base and community relations -- two of the major advantages of some local NGOs -- and community-based organisations may also be used for initiating a network or platform to bring thei together. The age-old indigenous practice of baidya is currently threatened by a host of problems, including limited availability of the required plants and herbs; rapid destruction of natural forests; lack of formal arrangement or institution to nurture this knowledge; lack of organised propagation nurseries; inadequate institutional and external support and patronisation (especially from the government); low quality and poor stock of raw materials in the open market; and unwillingness among the youngsters to learn and adopt the practice.

Despite the rather dismal present state of affairs, this deeply-rooted social practice, which has significant value as a community service, still holds great potential and is too important to be ignored, and, therefore, deserves the attention and support of all concerned. Dr. Niaz Ahmed Khan is Professor of Development Studies at the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh and Honorary Research Fellow, Centre for Development Studies, University of Wales, UK. Photos: AMIRUL RAJIV A. Z. M. Manzoor Rashid is Assistant Professor of Forestry and Environmental Science at the Shah Jalal University of Science &Technology, Sylhet. |