Inside

|

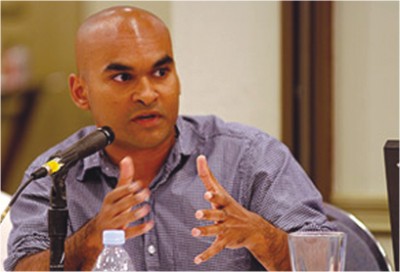

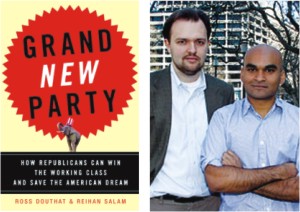

New Star Rising Razib Khan profiles Reihan Salam, an up-and-coming Bangladeshi-American thinker and writer

WITNESSING Reihan Salam speak off-the-cuff feels like some intensely demanding, habit-forming new spectator sport. While he's in full rapid-fire, animated flow, the rapt listener remains completely engrossed, delighted by his insights, analysis, and wide-ranging references, wowed by his effortless formulations and disarmed by his wry asides. Sadly, when Salam's flow ceases, typically abruptly and with a self-effacing apology for only covering one of his dozen intended talking points, the exposition of others threatens to leave the listener cold. Your mind wanders in the yawning pauses of another speaker's slow thought process and you wonder how people can take so long to formulate an idea. In that same time, Salam would have reeled off five perfectly print-ready, erudition-packed sentences, managed to mock his teenage self, veered dangerously close to an Elvis Costello impression, and from the looks of things, politely snuck a glance at the latest titles in his hyperactive email inbox. So, who is Reihan Salam? If you don't know of him yet, you will. Salam is an American-born son of Bangladeshi immigrants, Harvard graduate, prominent political blogger and journalist, and now co-author of a serious and fast-selling political manifesto Grand New Party. To add that he also blogs about pop culture doesn't begin to describe the man's breadth or curiosity. He has long posted original poetry and rap lyrics on the web and steeped himself in pop music, both Japanese and Anglophone. He recently treated his weblog readers to a brief, original audio-file of a flummoxed, sputtering immigrant South Asian shopkeeper confronting a boozy, unflappably warbling piano, a character remotely suggested by Tom Waits' The Piano Has Been Drinking. Flights of artistic fancy aside, whatever Reihan Salam does, he does with an abundance of focus and intensity. Nevertheless, he remains on good terms with intellectuals on all sides of a political argument; he can enter into passionate discussions about American macro-economic policy just as well as he fanatically dissects the plot twists in a hit television series. His boundless energy and generosity of spirit allow him to be the consummate connector, the nexus of social networks. Will Wilkinson, a researcher at the Cato Institute, says of Salam that he is the "Kevin Bacon of the young Bos-Wash political-intellectual scene," alluding to the trivia challenge to link any other actor to Bacon via the smallest number of steps possible. In a recent online conversation with friend and co-author Ross Douthat to promote Grand New Party, Salam nervously observed that many of the people with whom they were on good terms positively detested each other. Wilkinson admitted his own hyper-awareness of this reality when writing; in the back of his mind, he wonders whether he'll come to find out the foe he indicts is in fact another friend of Salam's. Arguably the most prominent American of Bangladeshi origin today, Reihan Salam's story beings in the New York borough of Brooklyn in 1979. He has stated on his popular weblog The American Scene that when his parents arrived in New York City in 1976 the Bangladeshi community consisted primarily of men associated with the shipping industry. In fact the census records fewer than 1,000 Bangladeshis in the city in 1980. Salam's father, Mr. Sarwar Salam, an accountant, recalls that his son's proclivities were clear at an early age. The younger Salam was not particularly interested in sport. Rather, he would read Newsweek, National Geographic, and Time cover to cover. Despite his son's bookish inclinations Mr. Salam sketches an otherwise relatively conventional childhood. Salam rode his bicycle around the neighborhood, was ferried back and forth from the comic store by his parents, and his elder sisters pitched in babysitting their much younger sibling. Dr. Jesse Shapiro, now an economics professor at the University of Chicago, was Salam's classmate at both the elite Stuyvesant secondary school and Harvard University. At Stuyvesant, where Salam was president of the debate team, Shapiro recalled an episode which hinted at both Salam's rhetorical forthrightness and intellectual depth. The former US Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, had been invited to address the student body. After his remarks, young Salam rose to ask a question, making a precise reference to an argument in one of Reich's books. Reich was shocked that such a young man was so familiar with his work, but Salam matter-of-factly responded that he was a "fan" and had read all of Reich's major writings. Dr. Shapiro, who earned his Ph.D. in economics from Harvard, doesn't recall Salam's question, explaining that it was far too advanced for him to comprehend. Not only does he completely immerse himself in each chosen milieu, Salam also moves in many disparate circles. One day might include an appearance on a panel in Washington DC soberly discussing the future of the Republican Party in the United States. The next day he might be dancing under the sun with fellow fans at a music festival in California, checking in via blog at the end of day to record his breathless approbation of a band he acknowledges as unseemly for a man of his age to worship. The elder Mr. Salam observed with bemusement that it was at liberal Harvard his son became a conservative. As a student he produced articles such as "The Confounding State: Public Ignorance and Politics of Identity." What may surprise those aware only of his substantial policy oeuvre is that Salam was also an avid actor during this period. According to Cary McClelland, a classmate who directed a theatrical troupe which spent summers in Britain, Salam brought the same intensity to his acting as he did to his social and political interests. Though occasionally Salam took a serious turn in productions such as King Lear, his forte was improvisation and comedy. A professional actor who was active in the same troupe, Emily Sophia Knapp, predicts that Salam's creative ventures will always remain an avocation, an ingredient in a full, rich life. According to Knapp at Harvard, Salam was an active member of the Signet Society, an exclusive club with a brief to foster the arts. The creative compulsion is key to understanding the full range of Reihan Salam's cultural production. While an undergraduate, he interned at the centere-left opinion journal, The New Republic, committing a number of articles to their archives. But the full effect of Salam's influence there is felt on The New Republic’s website; former associates periodically link to such straight-faced apolitical Salam frivolity as in his interpretation of The Piano Has Been Drinking, inevitably leading to confusion among uninitiated readers. Salam's friends make it clear that he is filled with a joie de vivre, which is contagious and infects all those around him, whether that means drawing an actress into an animated public policy discussion or plying an economist with his latest rap lyric. A heightened taste for the best of policy, improv, and everything good in between is a reliable by-product of association with the always impassioned Salam. How does he manage to achieve all this? Matthew Yglesias, a left-leaning pundit and fellow editor at The Atlantic called him "a blur of activity." Both McClelland and Knapp are similarly in awe of his energy. Dr. Shapiro admitted he wasn't surprised that his friend had become an author before the age of 30; he suggested Salam could have written a book as a teenager. Salam's reported daily intake at that time was one work of non-fiction per day.

After years of supporting the intellectual projects of others, Reihan Salam has come into his own as an editor at The Atlantic, the author of a prominent book, as well as taking a position as a New America Foundation fellow. A month ago The New Yorker magazine published a piece about the decline of the American conservative movement; the ideas in Grand New Party were highlighted as a response to the dispirited state of conservatism. I found it interesting that the article, and Douthat and Salam's mention, came to my attention in casual conversation with an entirely politically-unengaged friend. This is not exactly a case of Will Wilkinson's worry; my friends are not Salam's friends, but his name is becoming well known enough that I receive Reihan reports without requesting them. If a passion for the arts animates Salam's private life, clearly his public life is no less dominated by politics and policy. He has admitted a fondness for culling obscure dissertations for useful bits of data, and anyone who has spoken with him face-to-face is confronted by waves of information gushing forth. Knapp states with some justification: "He knows everything." Douthat's first impression of his future collaborator was tinged with "awe at his fearsome intelligence." But he goes on to add that what is special about Salam is "how genuinely interested he is in other people's ideas." Will Wilkinson echoed that sentiment, contending that Reihan's generosity is driven in part by his openness to friendship, his willingness to make connections with others. I find this crucial to understanding Salam's political passions. At the root of his efforts is a genuine empathetic humanism. His father recalls that as a teenager his son dragged both his parents to the voting booth. Salam once asked me if I was interested in making an impact on the world, and I admitted candidly that my focus was to learn about the world, not change it. In contrast, Salam is alive to the possibilities of other humans in a very visceral way of which I doubt I can fully conceive. Grand New Party, Salam's first book, is an expansion of the argument originally outlined in a widely discussed article in The Weekly Standard which focuses on "Sam's Club Republicans," the working class Americans who are attempting to maintain middle class lifestyles in a globalising world. They tend to live in the broad middle of the United States, they don't hold university degrees, and their lives are often characterised by the spectre of personal disorder. Salam and Douthat outline a project of the centre-right which makes conservatism more explicitly pro-family in a concrete manner with the aid of government incentives, an alternative both to the social democratic future which many left intellectuals are proposing, and the minimal state conservatism which is now the orthodoxy on the right. Some have observed that the authors of Grand New Party are Harvard-educated East Coast urbanites, so what exactly would they know about working class Americans? Yet this very focus on those whose circumstances differ so greatly from his own highlights Salam's lack of parochialism in his concerns. A young man of ferocious intelligence, unbridled spirit, and bottomless reserves of energy, Reihan Salam is only at the beginning of his public life. His interests are myriad and idiosyncratic, and the depth of his comprehension on a range of topics is vast. In the first 28 years of his life he has influenced his family and innumerable friends. The next step is to move to a broader stage and help shape the lives of his fellow citizens through his ideas, a synthesis of his analytic clarity and human empathy. Razib Khan is a UNZ Foundation Fellow. |

Reihan Salam has already worn many hats at a tender age. He has written for the left-leaning The New Republic and the right-leaning The Weekly Standard. There have been stints at The New York Times and at NBC Television. He researched for prominent conservative commentator David Brooks of The New York Times, and Andrew Sullivan, syndicated columnist and author of the weblog The Daily Dish. Salam has since become a colleague of Sullivan's at The Atlantic. The connections to Brooks and Sullivan both came about when Salam contacted them online out of the blue, the same unorthodox manner in which my own association with him began.

Reihan Salam has already worn many hats at a tender age. He has written for the left-leaning The New Republic and the right-leaning The Weekly Standard. There have been stints at The New York Times and at NBC Television. He researched for prominent conservative commentator David Brooks of The New York Times, and Andrew Sullivan, syndicated columnist and author of the weblog The Daily Dish. Salam has since become a colleague of Sullivan's at The Atlantic. The connections to Brooks and Sullivan both came about when Salam contacted them online out of the blue, the same unorthodox manner in which my own association with him began.