Inside

|

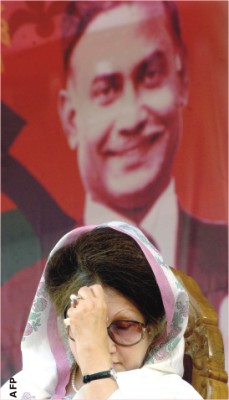

Handle With Care Mahmud Farooque discusses political dynasties

However, a comparable outrage by the same group was remarkably absent in considering the implications of a Hillary Clinton candidacy, which, if successful, would mean a Bush or a Clinton has been on the US presidential ballot for 28 years and counting. There is an internet site called Bush-Clinton Forever that charts a possible roadmap of keeping either a Bush or a Clinton in the White House till as far as 2057! So why does the prospect of a Hillary Clinton presidency not raise as many eyebrows among our progressive opinion-makers as does the prospect of a Bilawal Bhutto prime ministership? When asked, a vast majority of them point to the process, and argue that in the US case the outcome was merely the product of chance and not something determined through an autocratic decree or institutional design. Notwithstanding the disputed results in Florida, there would have been a first Gore rather than a second Bush in the White House in 2001 had the four electoral votes in the state of New Hampshire gone into the Democratic column. Hence, the principal arguments against dynastic politics stems from the lack of institutional safeguards designed to prevent the concentra-tion and transfer of power due to family lineage rather than due process, equal opportunity and political achievements. These considerations have recently and rightfully entered into the national discourse about political reform in Bangladesh, where its most recent 16-year experiment with democracy failed to wrestle power away from two dominant political families. Rather than risking a further continuation of this cycle, steps have been contemplated to leverage legal and institutional means to weaken, if not completely sever, the link between the two major political parties and the two families which have successfully allowed them alternate victories in the national elections. The idea is premised on the conventional wisdom that the strangleholds of these two families are standing in the way of internal party reform, without which it is impossible to rein in pervasive corruption, the deteriorating law- and-order situation, and the political stasis that have been stifling economic growth, social developments and large scale empowerment of the general citizenry. Hence the argument that the removal of these two obstacles is one of the essential ingredients for bringing about lasting democratic reform in Bangladesh. Of course (not that the two efforts are at all comparable), this is not the first attempt to cleanse Bangladeshi politics from dynastic control -- the previous one was in the most brutal manner imaginable. The coup of August 15, 1975, went so far as to kill every single member of President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's family who were within reach, sparing not even his 8-year old son or his expectant daughter-in-law. Yet 20 years later, it was his daughter Sheikh Hasina, abroad at the time of the coup, who successfully reinstated the Awami League back into the seat of power after a long and arduous political battle. During these times, the primary opposition in her political struggle also turned out to be the surviving family member of another assassinated president, and was equally successful in leading the party founded by her husband out of virtual obscurity to victories in two general elections. In light of these well known historical facts, it is therefore not unfair to ask: whether the phenomenon observed in Bangladeshi politics in the form of dynastic succession is indeed the product of institutional deficiencies or something else; whether legal maneuvers and institutional tinkering can actually end it once and for all; and whether reaching such an end will bring about the political stability so earnestly desired. To answer the first question, we turn to institutional structures in countries that have had successive democratic regimes over a sustained period of time. What we tend to observe is that in countries like France, Italy, Taiwan, and Singapore, where transaction costs are perceived to be high, there is an inherent difficulty in sustaining the development and growth of large organisations outside of the public sector. High transactions costs, some scholars argue, result from deficiencies in social capital. A crude mea- sure for social capital had been offered by sociologist Frank Fukuyama through a concept he calls "the radius of trust." Fukuyama argues that in certain societies, cultural propensities, emanating either from religion, custom, or history, make it naturally difficult to extend the radius of trust beyond the members of the immediate biological family. For large organisations to develop under such cultural propensities, the state has to play a larger role, either through direct ownership or by virtue of regulatory incentives and control.

When viewed through these lenses, Bangladesh, in its current stage of development, certainly exhibits many traits of a society where trust is generally lacking. There are strong social taboos and fundamental religious obstacles to accepting kinship outside of the bloodline. As a result, virtually all large private sector businesses and financial institutions are run by family cartels. The level of trust between the political parties is deemed so low that a neutral caretaker government has been constitutionally sanctioned to oversee the national elections and transfer of political power from one elected regime to another. It is thus not surprising that when the country was thought to be on the brink of an insurmountable political impasse bordering on civil war, people welcomed some kind of intervention by the nation's armed forces, arguably the largest non-market institution where professionalism, meritocracy, and due process are still the norm. The appearance of professionalism within the army, made more visible through its direct support of the current technocratic government, has given new fodder to the expectation that a cleansing operation, coupled with the enactment and strict enforcement of new rules and restrictive laws, will improve the governing structures within the political parties, creating a stable and predictable path to party leadership that is independent of family lineage. At first glance, such expectation will seem to be not only well grounded, but also highly desirable. Certainly, if it can be done for the armed forces in Bangladesh, why could it not be done for political parties? One seriously overlooked fact in that argument is that the conditions under which professionalism is developed and cultivated within the army are fundamentally different from the conditions under which a political party or a private enterprise generally operates. And this brings us to the second question: whether legal maneuvers and institutional tinkering can actually end dynastic succession once and for all. To adequately judge its effectiveness, one has to project the results of institutional reform to a period when the state of emergency has been lifted and people's rights to spontaneous political and social engagement have been restored. Under such a situation, the growth trajectory of political parties will not be shaped solely by rules and regulations governing political parties, but more critically through the interplay of institutional structures with political ideology, civil society and culture. And because it is the latter that is least amenable and most resistance to change, chances are that in the long term, the outcome will be shaped more by the strength of cultural tendencies rather than the weak institutional roadblocks designed to obstruct them. Hence, judging by the pattern of institutional developments in high-transaction cost countries, it is plausible to speculate that the leadership structure of political parties in Bangladesh will ultimately not be very much different from the dominant traits of its private sector and society as a whole. At the same time, while recognising its obvious negatives, one also has to admit that dynastic controls do provide a form of consistent political branding that is essential for holding together a weak coalition of many small personality-driven factions within the party that are also subjected to the same cultural propensities towards family-centric control. Indeed, among the noteworthy accomplishments of Sheikh Hasina and Khaleda Zia has been their ability to pull together the warring factions within their parties to string together a contestable coalition for competing in the national elections.

Such drastic measures, rather than paving the way for bottom up democracy to take root in Bangladesh, could actually hasten the case for frequent military interventions and further erosion of individual rights and personal freedom, making it even more unwelcoming for a new generation of leaders to enter the political system. A more pragmatic approach for the near term would be to recognise that the current leadership structures of the two major political parties do provide a modicum of internal cohesion within the party, which by extension provides some basic political stability needed to foster inter- and intra-party dialogue. This cohesion will be more urgently needed after the lifting of the state of emergency because a great deal of instability has been already been inserted into the leadership structures of both parties due to the imprisonment of many of their leaders and outlawing of political activities over an extended period of time. Instead of focusing on developing an exit strategy for the two leaders and expecting that it will cure all that ails our political system, a pragmatic alternative would be to take a holistic and patient approach and rely on the election process to loosen the grip of dynastic control through a process of evolution. Rather than trying to engineer a desired outcome, attention needs to be given to creating equal opportunities and devising a longer term strategy based on balancing the positives with the negatives, without losing sight of the ultimate goal of developing a due process, equal opportunity, and achievement based leadership structure. The argument that a new generation of leaders needs to be brought into the political process is not in doubt. However it is not going to occur if widespread instability persists due to inter- and intra-party fighting. Dynastic control of the political parties did not develop overnight. Dealing with it effectively will require recognising that the problem is multi-faceted and complex and will require constant adjustments, adaptations and changes in response to the crisis at hand, and not some idealistic projection of a perfect world in a sanitised setting. Mahmud Farooque writes from Indiana, US and is a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective. |

I

I

Notwithstanding these arguments, supposing legal and institutional maneuvering did manage to bar the dynastic leaders for now, would this bring the desired political stability? Unfortunately, the answer is likely to be in the negative The dismantling of the leadership structure through external means, apart from bringing questionable results in the longer term, also introduces the risk of injecting greater political instability in the short term by virtue of splintering, factionalisation, and further polarisation. This will make it difficult for any political party that emerges out of the next parliamentary elections to rule effectively without entering into some form of a loosely held coalition with many of its competitors. If it seemed daunting to reach a consensus to form a neutral caretaker government with two major political parties, imagine the insurmountable challenges when the numbers will be increased by a factor of 20, 30, or more.

Notwithstanding these arguments, supposing legal and institutional maneuvering did manage to bar the dynastic leaders for now, would this bring the desired political stability? Unfortunately, the answer is likely to be in the negative The dismantling of the leadership structure through external means, apart from bringing questionable results in the longer term, also introduces the risk of injecting greater political instability in the short term by virtue of splintering, factionalisation, and further polarisation. This will make it difficult for any political party that emerges out of the next parliamentary elections to rule effectively without entering into some form of a loosely held coalition with many of its competitors. If it seemed daunting to reach a consensus to form a neutral caretaker government with two major political parties, imagine the insurmountable challenges when the numbers will be increased by a factor of 20, 30, or more.