| |

SCIENCE FORUM

Ultimate Precision

Atoms and lasers -- inside the clocks of the future

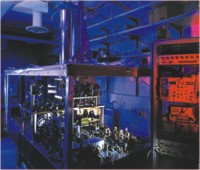

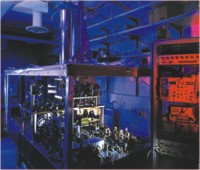

American physicists have created a clock so accurate it will not have gained or lost a second 200 million years from now -- good news for the most punctual among us though we may not be around to test the claim. American physicists have created a clock so accurate it will not have gained or lost a second 200 million years from now -- good news for the most punctual among us though we may not be around to test the claim.

The secret to making an extremely accurate clock is making it tick faster.

"If you make a mistake, you can know about that mistake very fast," said Jun Ye, who developed the atomic clock at the Joint Institute for Laboratory Astrophysics.

Ye's clock has 430 trillion "ticks" per second!

Its pendulum uses thousands of strontium atoms suspended in grids of laser light. This allows the resear-chers to trap the atoms and measure the movement of energy inside.

"Essentially, we are probing the energy structure of the atom. We are probing how electrons make transitions between a set of energy levels," Ye said.

"This is the time scale that was made by the universe. It is very stable."

The clock outperforms the current official atomic clock used by the US's National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), reports Science magazine. The latter is thought to remain accurate down to the second for 80 million years.

"These clocks are improving so rapidly that it is impossible to tell which one will be the best," said Tom O'Brian, head of the Time and Frequency Division at NIST.

In case you were wondering, such high precision clocks are critical for deep space navigation, where even the most minute errors can make or break a space mission.

To test his clock's accuracy, Ye and colleagues compared it with another optical atomic clock -- this one measuring calcium atoms. This calcium clock is highly stable only over short periods of time, so the researchers had to make fast measurements for their comparisons.

Next Ye wants to take on a clock that measures a single ion, or charged particle, of mercury. This clock, also developed at JILA, was accurate to about 1 second in 400 million years in 2006. Because Ye's clock measures thousands of atoms at once, it produces stronger signals, something Ye thinks may give him an edge.

"These clocks are among the best in the world," says John Lowe, leader of the atomic standards group at NIST. "Longer-term experiments will prove which of these clocks may end up becoming the next standard of international agreement."

Ye said pushing for ever more accurate clocks will allow physicists to test some of the basic questions about the nature of the universe.

Science Forum is compiled and edited by Rashida Ahmad.

Sources: Nature,New Scientist, Scienc

It all adds up: babies reveal humans' innate gift for numbers

They may seem to just eat, cry, sleep and fill their nappies, but 3-month-old babies may already be aware of how many animals are dangling from their mobiles. Researchers at the University of Paris-South in France have already shown that adults and 4-year-olds seem to process numbers in a particular part of the brain, separately from other information. To find out if 3-month-old babies did the same, the team fitted 36 infants with caps designed to record their brain waves. They discovered that babies have brain circuits dedicated to noticing quantity, adding weight to the argument that humans may possess an innate sense of numbers.

Even baboons need a daddy

It's not just humans who benefit from having a father figure around; according to new research, young yellow baboons are likely to grow up fitter and mature more quckly when their dad sticks around for a longer time. The discovery reveals there's more to male baboon life than sex and fighting, say scientists at Princeton University in New Jersey.

A step towards babies with three parents?

When British scientists were reported to have created so-called "three-parent embryos" last month, predictable media hype and outrage followed. But some of the reports have misconstrued what the scientists have actually done thus far, and the scientists caution that their unpublished work, while promising, is still far from clinical use. The Newcastle University team believe they have made a potential breakthrough in the treatment of serious disease by creating a human embryo with three separate parents. The embryos have been created using DNA from a man and two women in lab tests. The technique could help eradicate a whole class of hereditary diseases. But progress reports show clinical application is still far away.

Scientists simulate shape-shifting robots

Swarms of robots that use electromagnetic forces to cling together and assume different shapes are being developed by US researchers. The grand goal is to create swarms of microscopic robots capable of morphing into virtually any form by clinging together. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, admit this is still a distant prospect. However, his team is using simulations to develop control strategies for futuristic shape-shifting, or "claytronic," robots, which they are testing on small groups of more primitive, pocket-sized machines. These prototype robots use electromagnetic forces to maneuver themselves, communicate, and even share power.

2008: The start of time travel?

A pair of Russian mathematicians have made the extraordinary claim that, when the Large Hadron Collider is switched on in Switzerland later this year, it might turn out to be the world's first time machine. The LHC is the most powerful atom-smasher ever built, and particle physics could leap forward with its 2008 launch. Yet, if Russian mathematicians Irina Aref'eva and Igor Volovich are right, any advances in this area could be overshadowed. If their speculative time machine claim is correct, the LHC's debut at CERN -- the European particle physics centre near Geneva -- could be a landmark in history. If travel into the past is possible, it's only possible as far back as the first time machine. So 2008 could become Year Zero for future time tourists.

A man on Mars? Global effort needed for mission

The United States must collaborate with other countries to achieve its goal of putting humans on Mars by the 2030s, or it may fall short of its aims, scientists and former space officials said last month. A two-day conference at Stanford University backed greater international cooperation for a global program that would unite European states and more established space powers such as the US and Russia to further the goal of a manned Mars mission. Scientists say, because of Mars' orbit, a manned mission would involve a stay of either just seven to 10 days in a total mission of a year, or a three-year odyssey with more than a year on the planet.

For a healthy mind, just forget it

Some things in life are best forgotten. Studies show that having a normal healthy memory isn't just about remembering the important things. Its also about being able to forget the rest, reported New Scientist magazine last month. Unfortunately for AJ, a 42-year-old woman from California, forgetting is a luxury. Mention any date since her teens and she is immediately able to recall where she was, what she was doing, and what made the news that day. It's an ability that has amazed family and friends for years, but it comes at a price. AJ describes it as a "running movie that never stops." Even when she wants to, AJ cannot forget. She is one of a handful of people with similar abilities now working with neuroscientists to find out how and why they remember so much.

Live slow, die young

Sedentary lifestyles could make you old before your time. Active people could be up to 10 years "younger" than couch potatoes, according to one measure of biological age. The Twin Research Unit at St Thomas' Hospital in London, looked at the levels of physical activity of 2,401 twins and assessed the length of their telomeres -- the "caps" on the ends of their chromosomes that help to protect the DNA from wearing down during the replication process that replenishes cells.

Languages divide, then bloom

Linguistic evolution is marked by "punctuational bursts." Languages show periodic bursts of evolution, in which many new words blossom, according to new research that treats linguistic evolution like its biological counterpart. The research suggests that new words evolve slowly most of the time, but with spurts of diversification when two languages divide.

|

American physicists have created a clock so accurate it will not have gained or lost a second 200 million years from now -- good news for the most punctual among us though we may not be around to test the claim.

American physicists have created a clock so accurate it will not have gained or lost a second 200 million years from now -- good news for the most punctual among us though we may not be around to test the claim.