Inside

|

The Making of Muktir Gaan Catherine Masud tells the untold story of how this labour of love came to the screen It was in the fall of 1990. Tareque and I had been in the US for about one year. We didn't really have any particular plan in mind at the time for staying in the States. Rather, it was a "decompression" of sorts, after a hectic period in Bangladesh and India when we had struggled to complete The Inner Strength, Tareque's documentary film on the life and art of the painter S.M. Sultan.

In New York, Tareque was working in a famous used-book store called The Strand, and amassing an enormous collection of books on film and Indology in the process. I was an executive in an advertising agency, half-heartedly climbing the corporate ladder. We were both looking for something inspiring to throw ourselves into, but weren't quite sure how and where to start. At that time, we were spending almost every weekend with my brother Alfred, who was completing his post-doctoral work in physics in Princeton, New Jersey. One day he was stopped on the street by a South Asian-looking woman who needed directions to the physics department. They began to chat -- she said she was originally from Bangladesh, and Alfred said his sister was married to a Bangladeshi. One coincidence led to another, and it turned out she was the wife of Tarik Ali, an old friend of Tareque's first cousin Benu. The Alis lived in the neighbouring town of Lawrenceville, and the following weekend found us sitting cozily in Tarik bhai's living room, exchanging stories of Dhaka and dreams of return. The conversation drifted to the Liberation War. Tarik bhai and Tareque's cousin Benu bhai were together at that time, singing in a cultural squad of refugee artistes. Tarik bhai recalled that an American film-maker and his crew had traveled with them for some time, documenting their experiences during the war. Tareque vaguely remembered that in the early 1970s, Benu bhai had often mentioned this film-maker in passing during reminiscences of the war. His name, according to Tarik bhai, was Lear Levin. We were immediately intrigued. What an unusual name: Lear. It conjured up images of grandeur and tragedy. What had become of his footage? Perhaps it was a journalistic catalogue of events of the war. Certainly Lear no longer lived in New York. Perhaps he was long since dead. Over the next week or so, Tareque and I gradually forgot about Lear Levin. But the following Saturday, I was suddenly inspired to pick up the phone book and look through the Ls. There were pages and pages of Levins. But suddenly, there it was. Lear Levin. And Lear Levin Productions. I am always nervous about phone calls, so I handed the phone to Tareque. He called the production office -- it was the weekend, but he could leave a message. But someone picked up the phone. Tareque: Yes, I was trying to reach a Mr. Lear Levin. Mahmoodur Rahman Benu is my first cousin. Do you remember Benu? At the sound of Benu's name, Tareque could almost feel, through the telephone line, a rush of emotion overtaking Lear. Lear: Of course I remember him. Well, in 1971 I was a young man, 30 years old. I went to Bangladesh to make a film about the Liberation War. I put a lot of myself into that film, a lot of money and time, but eventually I had to abandon the project. And now, you have called. I've been waiting almost 20 years for this phone call.

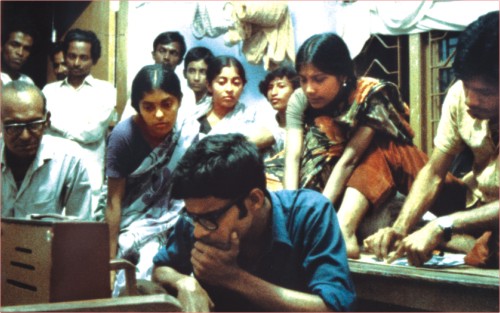

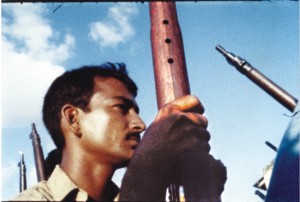

And so began the Muktir Gaan project, which eventually stretched over five long years of struggle and sacrifice. But this is not an account of the peripheral dramas and pitfalls that we stumbled upon in our efforts to complete the film. Nor is it a catalogue of the trials and tribulations of our struggle to get the film past the censors and successfully released, despite attempted banning and the lack of any distributor, or about the years we spent traveling with the film to show it in hundreds of towns and villages around the country. Rather, this is an exposition of the making of the film itself: its evolution as a creative work, its structure, and the various and disparate elements that were woven together to make a complete film. Although this exposition may tear away the documentary façade of the film, it will also illuminate the true process behind its making which this façade obscures. Not long after our telephone conversation with Lear, we met him at Film Video Arts, a film-maker's cooperative in Lower Manhattan where we often rented equipment at cheap rates. Lear, a tall, athletic man, looking far younger than his 50 years, had brought along a couple of cans of his footage. At this point, we were not expecting more than a few minutes of black and white newsreel. So we were completely overwhelmed when the editing machine began to play back pristine, full colour images of Benu, and so many other familiar faces from Tareque's childhood, all fresh and glowing with youth and the ideals of 71. Tareque nearly began to cry. And then Lear said there were another 19 hours of footage still lying in his basement. A few days later, we went to Lear's home on the upper West Side of New York City to begin the lengthy process of studying and cataloging his footage. His basement was not the dusty dumping ground typical of many homes; it was the storage centre of a professional film-maker, and as such, was professionally maintained. It was clean and cool and the walls were lined to the ceiling with shelves of film cans and boxes. He pointed to one particular wall and there we saw a series of cardboard boxes unobtrusively stacked for posterity. They all bore a distinguishing hand written label: "Bangladesh." Over the next five days, using simple viewing equipment, we wound through hours and hours of film in Lear's basement. There were 91 rolls in all, approximately 36,000 feet or almost 20 hours. What unfolded before our eyes was a beautiful document of the birth of Bangladesh. It contained exquisite, poetically photographed footage that attested to the genius and sensitivity of Lear Levin as a film-maker. A major portion of the footage centered on a troupe of musicians, Bangladesh Mukti Sangrami Shilpi Shangstha (Bangladesh Freedom Struggle Cultural Squad), which was traveling and performing throughout the border zones during the war. There was also some material on their interaction with the Freedom Fighters during a brief visit to a liberated zone in late November. In addition, there was a significant portion of Lear's footage that did not concern the troupe or the Freedom Fighters. This other footage primarily consisted of Lear's beautifully shot pastoral images of rural Bengal: farming, bathing, people going to market, cow carts, river scenes. Additionally, there was extensive footage of the minutiae of life in the refugee camps which we felt could be a separate film in itself: refugee women cooking, children fetching water and bathing, people receiving rations, refugee children being inoculated, etc. In fact, this material had formed the thematic backbone of Lear's edited version of the footage, made in the months after his return from Bangladesh. Entitled Joi Bangla, this film was essentially humanist in its approach, focusing on the spirit and beauty of the people of Bangladesh with the war itself as a distant backdrop. Unfortunately, Lear's film never reached its intended audience; the Liberation War came to an end shortly after Lear's return to the US, and after months of labour on his edit he found that the tide of interest in Bangladesh had swiftly receded. Lear could not get funds to complete the film, and so the project was shelved, literally, on the walls of his basement for almost twenty years. We set to work. We were then living in a sleepy part of New York, Staten Island, which was a 30-minute ferry ride from Manhattan. Here, in our little house on a hilltop overlooking the city, we could work undisturbed. The 20-odd boxes containing Lear's footage were transported to Staten Island in my brother's car. After viewing the footage in its entirety, we tried to draw up a treatment plan for the film. Beautiful as it was, Joi Bangla was a completely different film than the one we wanted to make. Rather than targeting a foreign audience, we wanted to make a film that could speak to contemporary audiences in Bangladesh, particularly to a new generation of young people for whom the Liberation War was nothing more than a confused legend. Our emphasis was the cultural troupe itself: their day-to-day experiences, their struggles, and most of all, their music, through which the story and spirit of the Liberation War could be conveyed to a Bangladeshi audience. We therefore bypassed most of Lear's extensive and beautifully shot footage of life in the refugee camps and an idealised rural Bengal. Initially, we thought of adopting a conventional "then-and-now" approach, with interviews of the troupe members reflecting on their experiences in 1971, interspersed with Lear's footage of the troupe during the war. However, our thinking shifted as we began to feel that this type of approach would not appeal to general audiences in Bangladesh, particularly to a younger generation of people who had not seen the war and might have trouble identifying with the older troupe members. We decided to adopt a more narrative approach, building on the story of the troupe in 1971 and giving the film a strong musical and "road movie" structure, using the songs sung by the troupe. Our initial impression at this stage was that the thread of a story surrounding the cultural troupe was sufficient to stand on its own. In a single night we made a video rough cut to be used for fund-raising purposes that exclusively focused on the troupe and its activities in 1971. The linear and episodic nature of the story surrounding the troupe had its natural conclusion with the cultural squad's visit to the liberated area and this is the way we structured the loose narrative. We also included in this rough lineup another aspect of Lear's footage that, along with the images of the troupe, had an exceptional quality of timelessness. These were the numerous close up portraits of ordinary Freedom Fighters: listening to the troupe's music, caught in the rain, or just standing by the roadside. No typical news cameraman would or could have taken portraits of such startling perception. In the course of our fundraising shows of this rough video version for probashi audiences, we were able to get extensive feedback. This feedback was helpful to us as we began our work on developing a script for the final film. The story of the troupe that we had assembled from the available Levin materials proved to be too loose to hold audiences' attention. It required a tighter narrative with more substance, although we shunned the idea of using a commentary with footage that was otherwise so personal and subjective. In addition, some people who saw the video told us they wanted to see more about the war itself.

Considering these reactions, we decided to incorporate two major elements into the film: archival footage from other sources and a first-person commentary to provide a narrative glue for the story. In the fall of 1992, we spent an isolated weekend at my grandparents' home in Connecticut and hammered out a preliminary script for the film. This script required considerable amounts of stock footage on aspects such as genocide, battles, the refugee exodus, and the victory celebration. As part of this script we wrote out a rough rendition of a narration from a cultural squad member's point of view. The vehicle of our narration was Tarik Ali, chosen because of his prominence in the footage and because of his naive, lighthearted character that could appeal particularly to young audiences. We adopted a restrained, minimalist style in the narration that would complement rather than direct the images. This original narration was written in English. Later, our friend Alam Khorshed, then based in New York, made a translation into Bengali. We also made a list of songs to be included in the film that were known by Tareque to have been part of the troupe's repertoire, but were not part of the original recordings from Lear's materials. These songs would also have a significant role in holding together the story because of the way in which we intended to use them as a narrative for the accompanying images. After the basic scripting was done, we began the tedious and time-consuming process of editing the footage. We had already quit our regular jobs so that we would have time to work on the film; now we threw ourselves into the editing process with exclusive attention. We rented a film editing machine on a monthly basis, and had it installed in our home. Before actually beginning our edit, we had to go through an intensive phase of logging and transcription work. Our assistant editor was Dina Hossain, who was completing a Masters degree in film and anthropology at New York University. She would make the long trek from Brooklyn by subway, ferry, and uphill walk to our house, often working all night with us. It was a massive task to go through the 91 rolls of film, precisely logging them shot by shot in the computer. At the same time, we began our research work into archival footage, faxing back and forth to CBS and NBC in New York and ITN, BBC and Visnews in London. Bombay Films Division also had a considerable amount of material, some of which had been shot by Sukdev for his documentary "Nine Months to Freedom," and some of which had appeared as part of a weekly newsreel series on the war. Films Division also had the negative of Gita Mehta's "Dateline Bangladesh," which had some very good action shots of Freedom Fighters. By early 1993, we had created a basic edit structure of the film in preparation for a trip to Bangladesh, where we planned to do the main dubbing and recording work for the film. We brought Benu bhai with us from London, and had an emotional reunion with all of the troupe members together once again after 22 years. On a film editing machine at the national archives, we showed them two of the completed sequences from the film, "the Boat Crossing" and "Janatar Sangram." Some of them cried, others watched in excitement as the images of their youth played before them of the screen. Over the next several weeks, we had a series of sessions at FDC and an audio studio where the songs and dialogue were recorded. Many of the songs seen in the final film were recorded during this time. We also put the finishing touches on the narration in preparation for recording. We decided to record the narration with Tarik Ali rather than a professional actor because we wanted a natural, understated reading. This proved to be the right decision as eventually we recorded an unassuming rendition that was perfectly in tune with the documentary character of the film. After the main recordings were complete and Benu bhai had returned to London, Tareque made briefing of his troops. This sequence, of a supposed confrontation between the Pakistan army and Freedom Fighters, was edited together using unrelated footage from Bombay and London. It was more or less complete, but we felt it needed a proper celebratory conclusion. Tareque had brought back some very powerful footage from Sukdev's film of hundreds of Freedom Fighters shouting slogans which we thought might be appropriate. We initially planned to dub the slogans, but when we ran it on the editing machine, we realised it was impossible to read their lips. We needed the original audio. a trip to Bombay to purchase Films Division footage. We were looking for action shots of Freedom Fighters as well as refugee footage. Although there was ample footage of life in the refugee camps in Lear's footage, he was in West Bengal and Bangladesh for shooting in late October and November, too late to capture the massive refugee exodus across the border. Tareque spent a week in Bombay, going through hours of newsreel material as well as Sukdev's and Gita Mehta's work. The advantage of the Bombay footage, as compared with other archival sources, was that most of the footage was in 35mm colour, the eventual format for our film. Tareque was able to collect most of the footage he was interested in, except for Gita Mehta's material. Apparently Films Division could not sell this footage without Ms. Mehta's permission. She lived abroad in New York, so this phase of archival collection would have to wait until our return. In addition to the colour footage from Bombay, Tareque found a considerable amount of very important black and white footage of guerrilla activities and the refugee exodus, which we decided would be perfect for a pre-title sequence on the historical background of the war. When we returned to New York and began the process of integrating the new material into the film, the structure began to evolve further. We decided that the pre-title sequence would be incomplete without the inclusion of Sheikh Mujib's March 7 racecourse speech. The complete speech was available in black and white 35mm, but the original negatives were back in Dhaka. We then went through an arduous process of having a duplicate negative made, sending special duplicating stock from New York for processing in the laboratory in Dhaka. We also felt that it would be important to include Major Ziaur Rahman's radio announcement in the pre-title sequence, which we finally tracked down at Deutschewelle (German Radio) Archives. We used this audio with Films Division footage of a group of Freedom Fighters sitting around a radio while cleaning their weapons. We also began the task of laying down the new audio tracks of the songs and dialogue that we had recorded in Dhaka, along with the narration. Up to this point we had been able to edit together individual sequences; now, the total structure of the film began to fall into place. However, there were some gaping holes. We were still missing a considerable amount of colour archival footage, which we would need to purchase from commercial libraries in New York and London. The last part of the film was still very problematic for this reason, because we did not want to end with the troupe's visit to the liberated zone, but rather with the end of the war itself. Since this historical dimension was missing from Lear's footage, we would have to rely heavily on archival materials and audio manipulations to give the feeling of the events leading up to the victory celebration of December 16, which was to mark the end of the film according to our script. We needed additional footage of guerrilla activities, of the allied army advance, and the victory celebration itself. In order to bring in the international dimension, we decided to incorporate a segment from Bhutto's dramatic last speech at the United Nations. In addition, we wanted to use unrelated footage of the troupe traveling by truck and, through audio manipulation, make it seem as if they were returning to Dhaka at the end of the war. We had very colourful footage of the troupe singing a traditional kirtan in the truck, led by Shapan Chowdhury, which was otherwise irrelevant to our story but could be dubbed with a new song. While in Bombay, Tareque had begun work on this song. It had wording which was close enough to the original to match the troupe's singing, but with new lyrics that made reference to the rout of the Pakistan army and the troupe's return to a liberated Dhaka. This song, and the picture editing to match it, took months of painstaking labour to complete. It was finally recorded with some of our friends in New York, with Sudipto Chatterjee singing Shapan's voice and Mahmood Hasan Dulu playing the instrumental accompaniment.

To give additional strength to the concluding part of the film, we wanted to bring back the Yahya Khan puppet, and give him a monologue, written by Tareque, that would relate the retreat of the Pakistan forces with Bhutto's desperate last speech at the UN. This monologue was also recorded with our talented friend Sudipto Chatterjee. Another sequence at the end of the film that required some audio manipulation was the scene where a group of Freedom Fighters were shown caught in a rain storm. Lear had been stranded in the rain with these guerrillas, and not wanting to waste a moment of shooting time, he had used the moment creatively to capture some beautiful portraits of the fighters waiting out the storm. We wanted to use this footage as a bridge between the exuberant scenes of guerrilla preparations for battle that were shown with Jessore Khulna and the later marching sequence of Bangla Mar. However, we felt there wasn't enough substance to the storm sequence. We decided that in order to strengthen the feeling of a temporary depression in the mood of the narrative, we would use a broadcast of Akash Bani (All India Radio). Debdulal Bandopadhaya had a regular program in 1971 which broadcast news of the war, and many of these broadcasts contained moving references to individual experiences of suffering and genocide. Together with the pensive portraits of the guerrilla fighters, this broadcast would create the depressing feeling we wanted to evoke. The question was, what had become of the man who would be most helpful in tracking down this audio, Debdulal Bandopadhaya. Some of our friends in New York told us that he was long since dead; however, after several phone calls to Calcutta, we found that Debdulal was very much alive. When we finally spoke with him directly, he was more than willing to help us. Although he had retired from Akash Bani some years before, he still had many contacts there, and he himself went to the archives to search for the audio. However, this search was futile, as Akash Bani, in order to clear their store, destroys archival material after ten years of storage. Thus, the original 1971 recordings had been destroyed in 1981. However, as it turned out, Sattyen Mitra, who used to write the programs, had saved some of the original transcripts, and the text of these transcripts was perfect for our purposes. We decided to re-record the audio with Debdulal. For this purpose, a friend of ours, Junaid Halim, traveled to Calcutta and worked with Debdulal to make an effective recreation of the original. Debdulal's eyesight was very poor, so we made an enlarged computer printout of the text and faxed it to Debdulal to read. Three of the programs were recorded and FedExed to us in New York. From these three we edited a single story about the sufferings of wounded guerrilla fighters. We also needed some visuals of an old radio, in a similar setting, to intercut with the portraits of the Freedom Fighters. With Junaid's help, we arranged for Baby Islam to shoot this material based on our visual descriptions. This film was also express mailed to us and edited into the film. In January 1994, I made a trip to London to acquire archival footage. In one continuous seven-day period, I viewed roughly 30 hours of footage on the war, mostly at ITN. Although ITN was relatively inexpensive by archive standards (roughly 600 taka per second including duplication costs), it was still very expensive by our standards. Nevertheless, I ended up purchasing extensive footage of the refugee exodus, genocide, guerrilla activities, battle scenes, guerrilla hospitals and the victory celebrations. I also purchased footage from Visnews, which was more expensive but very crucial for our reconstructions of actual battles. In fact, Gita Mehta had used archival material in her film, and I was very lucky in tracking down the originals of most of the footage we were interested in London. However, there were still some important shots that we needed from her film, and when I returned from London we desperately tried to reach her in New York. However, as the wife of the chief executive of one of the most prestigious publishing firms in the world (Knopf), Gita Mehta was extremely difficult to track down. For three months we tried to get her telephone number from various sources, but even her own niece wouldn't disclose it. Finally, after we left a message at Knopf with her husband's secretary, she called us, and immediately gave us permission to use her footage in our film. We then faxed her signed permission letter to Bombay Films Division, and waited for a response. We waited for months, in fact, and finally gave up because of the difficulty of tackling the bureaucracy long distance. In the meantime, there were still several parts of the film that needed to be developed. We had constructed a daytime ambush sequence to follow Major Gyash's briefing of his troops. This sequence, of a supposed confrontation between the Pakistan army and Freedom Fighters, was edited together using unrelated footage from Bombay and London. It was more or less complete, but we felt it needed a proper celebratory conclusion. Tareque had brought back some very powerful footage from Sukdev's film of hundreds of Freedom Fighters shouting slogans which we thought might be appropriate. We initially planned to dub the slogans, but when we ran it on the editing machine, we realised it was impossible to read their lips. We needed the original audio. Also, we decided we needed footage of bodies floating in the water to go with the lyrics of Amar Bangladesher Gaan. I had not seen this type of footage in London, and the New York footage we had viewed was not very well shot. However, Tareque had seen some very good footage shot by Sukdev in Bombay of massacred bodies floating in the river. It seemed we would need to purchase more materials from Films Division. However, short of one of us going ourselves, we asked one of our friends in Bombay, who was an editor, to track down the material that Tareque had already viewed and logged. While our friend was collecting this footage, she stumbled across the news that our request for permission to buy Gita Mehta's footage had been granted some months back. So in the end we were able to purchase everything we needed from Bombay. Now that most of the picture editing was complete, we were ready for the final, and complex, work of editing and mixing the audio tracks. We used an advanced computer-based system for this purpose, which allowed us complete control over incredibly complicated edits and mixes. We were lucky to find a reasonably priced facility which provides services for independent film-makers. Using cutting-edge technology, tiny noises were eliminated, old voices were made young again, and effect sounds were painstakingly synchronised with the picture. Without this system, in fact, it would have been impossible to complete Muktir Gaan in its present form. The kirtan sequence of the troupe singing in the truck, for example, required 20 separate sound channels and elaborate editing to create the illusion of synchronous sound. In the pre-title sequence we layered track upon track of sound to create a dramatic audio montage of the UN debates, refugee distress and battle sound effects. Major Gyash (now Bir Bikram Brig. Gyashuddin Chowdhury) came to New York and dubbed his audio, which was very weak in the original, directly into the computer. He also extremely helpful in advising us on various military commands for which we had no audio, and accordingly we dubbed them using Tareque's and Sudipto's voices. Also dubbed into the audio track were numerous "Joi Banglas." The pre-title "Joi Bangla" of a soldier shouting into a megaphone is really Tareque's voice; the "Joi Bangla" slogans shouted by Freedom Fighters in gun boats were actually recorded by us in back of a school in Brooklyn, using the shouts of a group of probashis and synchronising them later on the computer. In fact, most of the audio in the film is pure trickery. Tarik Ali's Joi Bangla, Banglar Joi whistle at the end of the film is actually mine; Tarik Ali was in fact whistling Tchaikovsky, which we felt wasn't relevant for a jubilant scene of the troupe traveling to celebratory Dhaka. The sound effects of the Freedom Fighters crawling through brush were actually created by me, as I crawled through the fields in back of my grandparents' house. We also drew upon extensive libraries of sound effects on CD and tape, which had detailed labels such as "three inch mortar fire," "steam engine train," and "old truck starting." This laborious process took six months to complete. Ironically, it was this effort to create a flawless sound track that eventually reinforced the impression of documentary "reality." Even as we were finalising our audio, we were working on one final aspect of the film's structure that was yet to be complete. We had tried to bring in the wider aspect of the Liberation War through our extensive use of archival footage, but the only footage of guerrilla encounters we could find involved daytime actions. This was because very few film crews would risk their lives (or the lives of their subjects) by shooting after dark during wartime, and none would dare do so in the midst of a military operation. However, an accurate portrayal of the Liberation War would have to include night battles, as most of the guerrilla actions took place after sundown. We felt that it was a distortion of history to show only day battles, so we took creative freedom in reconstructing a night action, using actual Freedom Fighters at the actual location (Savar) where a battle had taken place. Over three intensive nights of production this battle was shot, using Freedom Fighters as leaders and trainers and younger boys as extras, in a swampy area off Aricha road where a bridge had been blown up in 1971. In fact, for authenticity, the "younger boys" were recruited from the armed cadres of local gangs, chosen because they could handle weapons convincingly. They worked with extreme dedication and sincerity, belying the commonly held notion that all hoodlums are hopeless criminals. It is a sad testament to the battles still being waged today that three of the youths were killed a few months later in random street violence. The edited version of the night battle sequence was express mailed to me in New York, where I incorporated it into the film and added the sound effects. Also sent along with the night sequence was an instrumental rendition of Janatar Sangram, beautifully arranged by Sujeo Shyam. This piece put the finishing touch on the poignant portraits of Freedom Fighters seen at the end of the film as Tarik Ali gives his concluding narration.

When our audio was finally finished and all the picture elements complete, we sent the film to one of the best labs in the United States, Cinema Arts in Pennsylvania. This was, incidentally, the same lab where Merchant Ivory had sent Pather Panchali and other Satyajit Ray classics for rejuvenation and fresh prints as part of a worldwide re-release project. The lab is housed on the side of a mountain in a remote area of Pennsylvania, in what used to be a storage facility for rare works of art owned by a reclusive philanthropist, John Allen. Through their delicate work of colour correction, we were able to achieve smooth transitions between shots from different sources and formats. At this very critical and expensive laboratory phase, we were very lucky to receive financial support from freedom fighters Shahidullah Khan Badal, Nasiruddin Yousuf Bachchu, and Habib Khan. In the spring of 1995 the film was finally finished. When we had our first viewing of a crisp print fresh from the lab, we had the same feeling of emotional estrangement we'd often had while viewing our work in our isolated retreat on Staten Island. In fact, we couldn't really feel anything when we saw the film, aside from relief. Over five long years we had toiled on this project, and seeing the finished film, we could only remember the many sacrifices and contributions of all the people behind the scenes who'd made it possible: Lear's generosity, Dina's voluntary effort, our landlord's tolerance, the contributions of hundreds of probashis, the involvement of the original troupe members, and so many others. At times during the production we had felt consumed by an obsessive desire to collect more material, to incorporate more and more elements into the film, and to perfect our work. We also had many moments of depression, when we despaired that the film would ever be finished. In the midst of our labour, it was impossible for us to gauge the impact it might have on an audience in Bangladesh. Little did we imagine the response that awaited us, so many thousands of miles away. And little could we imagine the struggles that awaited us even after the film was finished: the struggle against censorship, the struggle to find a distributor, the struggle to exhibit the film ourselves … But the story of the release of Muktir Gaan, and of the pleasure and pain which surrounded it, is a completely different one, to be told at a different time. This story, of the making of Muktir Gaan, is now complete. Catherine Masud is a Film-Maker. |

|

They felt the film had an overly "middle-class" character because of its exclusive emphasis on the troupe. They wanted footage of battles and genocide, they wanted more action images of Freedom Fighters. Others felt there should be references to some of the war's major events. Some conveyed their disappointment that there was no footage of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

They felt the film had an overly "middle-class" character because of its exclusive emphasis on the troupe. They wanted footage of battles and genocide, they wanted more action images of Freedom Fighters. Others felt there should be references to some of the war's major events. Some conveyed their disappointment that there was no footage of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.  This sequence gave credence to the final scene where the troupe is seen joining the street celebrations in Dhaka. In fact, the troupe was never there, but we intercut close shots of the troupe (actually in a refugee camp) with archival shots of the victory celebration in order to create this impression.

This sequence gave credence to the final scene where the troupe is seen joining the street celebrations in Dhaka. In fact, the troupe was never there, but we intercut close shots of the troupe (actually in a refugee camp) with archival shots of the victory celebration in order to create this impression.