Inside

|

Fighting Corruption:Do We Have a Flawed Approach? We need to focus on reforming institutions and not individuals, argues Mridul Chowdhury During the past year, there has been significant rejoicing over the capture of some corrupt government officials who have amassed huge amounts of wealth through manipulating loopholes in government procedures. The rejoicing is understandable, but what is sad to see is that there is so little talk about the very loopholes that have allowed these individuals to suck out money illegally from helpless citizens. The Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) seems to have taken on a rather narrow-minded mission to strike at corrupt individuals, and has largely failed to bring to light the sources of these corruptions in the government.

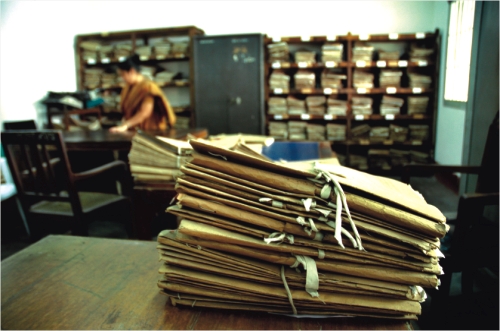

I once had to go to the Revenue Department of a government telephone office in Dhaka, where they keep track of phone bills and payments, and came across a startling discovery. The entries in the huge register books that kept track of this information were in bold and clear figures -- however, they were written in pencil! If you know how to satisfy a clerk or an official who has access to these register books, all it takes is a simple "eraser-action" to put your records "straight." When the procedure is that simple, how do you blame the clerk or the top government executive in the office who is turning a blind eye to this or maybe even the person running the country? We have to realise that corruption in the government is fundamentally a result of simple economics -- that of demand and supply. When there is demand for citizens in paying a little extra to "straighten records" or to receive a government service faster, and there is supply from government officials in providing "premium service" for an extra fee, corruption will always be there. Taking out the players while keeping the system intact will only serve to replace old players with new ones. The playing field will remain the same, and so will the rules of the game. While the national anti-corruption drive, including the revamped ACC, can claim some major early successes in putting behind bars some of the top godfathers who have allegedly been perpetuating corruption at every sector of the government, the ACC should really be focusing on the following strategies if it really wants to meaningfully fight corruption in the government: 1. Identify sources of corruption in the system of infamously rotten government offices that allow corruption to perpetuate -- there are always ways of clamping down on "eraser-action" rather than the "eraser" itself.

2. Once the sources are identified, revise the government procedures so that "figures are written in non-erasable pen-ink." 3. Strengthen accountability structure in the office so that any case of corruption becomes the responsibility of not only those who are committing the crime but also of those who manage the process. With such knowledgeable advisors in the current caretaker government, there is no reason why the government will not be able to take a broader view of fighting corruption and emphasise institutional building, rather than temporary witch-hunts that will not have lasting impact. This government has to realise that it can only leave a meaningful legacy if it can "straighten" the procedures of government institutions that deliver key services to citizens so that the scope for "eraser-action" is eliminated or minimised. In view of the fact that corruption in the government has become so endemic that finding "erasers" one by one can be a never-ending process, and given that the caretaker government is in power for less than a year, the government should really re-strategise and focus on institutional re-building since only that can ensure a long-lasting impact of the current anti-corruption drive.

Law and order However, so far, the anti-corruption drive itself has largely left the judicial and police systems to their own devices. There are indications that the police and the justice systems have internally become less averse to individual-level corruption since this caretaker government took over, but leaving these crucial institutions out of the anti-corruption drive equation in many ways leaves its most vital element out. While the commission can leave much of the implementation of the anti-corruption drive inside these institutions to the respective executives of these institutions themselves, it is important that the commission perceive this as a fundamental pillar of the drive. Not too long ago, there was much attention paid to the case of Ali Hussain, who spent 15 years in jail without a trial-- a somewhat dismal reminder of an unjust judicial system. Also, there have been repeated uproars against controversial judges whose neutrality towards political interests have been brought into question. According to Transparency International's Global Corruption Barometer 2007 findings, "the general public believe political parties, parliament, the police and the judicial/legal system are the most corrupt institutions in their societies." In the current context of Bangladesh, when the political parties are like crownless princes and the parliament good only for housing high-profile political prisoners, what we have with respect to "corrupt institutions" are the police and judicial/legal system -- and without reform, no anti-corruption drive can gain full credibility. IT systems in the government

technologies to address endemic problems of corruption in the government. Going back to the example of "eraser-action," if the entire system of data entry and update had been in a computerised system with several levels of security access to minimise chances of manipulating data, then we could go from a "pencil world" directly to a "computer world" without the need for passing through the "pen world." Several advisors in the current government come from professions which have equipped them to clearly see the power of IT systems to re-haul the efficiency and accountability of government institutions in many cases. Talking to them about what IT systems in the government can achieve in terms of fighting corruption would seem like preaching to the converted. However, it is again sad to see that this is an area that this government has put relatively little emphasis on. For instance, the Support to ICT Task Force (SICT) Project at the Planning Commission which was started several years ago to initiate pilot electronic government (e-Government) projects is nearing the end of its project duration. There is little effort from the government to try to learn from the experience of this project so that government institutions can learn from its achievements and mistakes. Disowning efforts started by previous governments, whether good or bad, is a custom long practiced in Bangladesh -- this government can perhaps try to break the cycle. Also, UNDP's e-Development Cluster has been engaged in providing capacity building and technical assistance to high-level government officers, which have for the most part remained under-utilised by the government. It is crucial that the national anti-corruption drive incorporates strategies to end corruption in governance systems and embrace e-Government as a possible tool. While it may not be possible for the caretaker government to make substantial progress in this respect in only a few months, the least it can do is to try to link the anti-corruption drive with possible solutions to fix the systems and explore how e-Government can support in this process. It may very well be argued that IT systems at the end of the day are under control of human beings and are subject to just as much manipulation, but it is also true that with sincere intentions, IT systems gives powerful options for creating adequate levels of check and balance so that any unwanted "eraser-action" will leave a digital trail -- something that is not possible in a manual system. Conclusion Also, another danger of an Anti-Corruption Commission is that given its lack of internal check-and-balance, this kind of an organisation may be misused if its control is taken over by biased groups or individuals. Considering all this, the government should look more seriously into reducing loopholes in government procedures in key institutions, including the justice and police systems, as the central element of the anti-corruption drive. Mridul Chowdhury writes from Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government.

|