Inside

|

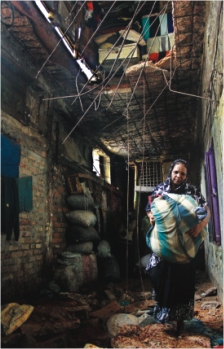

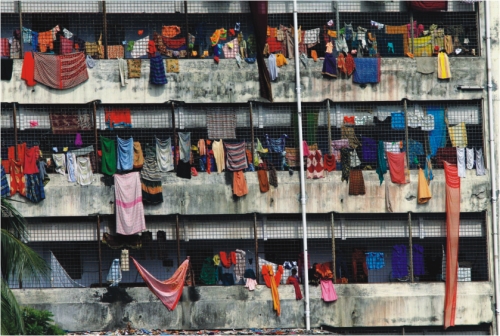

Urban Poverty Ashekur Rahman shines a light on how stronger municipal bodies are needed to tackle rapid urbanisation This year, for the first time in human history there will be more people living in the world's cities and towns than in the countryside. But this growth is not happening evenly across the world: urban settlements in developing countries are, at present, growing five times as fast than those in developed countries. Bangladesh is facing a potentially disastrous time with regards to the ever-increasing urban population. Trends show that the urban population growth rate currently stands at 3.5 percent per annum, almost more than twice that of the rural sector, and should it continue, more than 50 percent of the population will become urbanites by the year 2030. Dhaka has amongst the highest urbanisation rates in the world with a population already over 12 million; it is projected to grow to 20 million in 2020, making it the world's third largest city. The 2005 survey of the six City Corporations estimated that 35 percent of the urban population lives in slums, with the figure for Dhaka being 3.42 million (37.4 percent ) and for Chittagong 1.47 million (35.4 percent ). Information on urban poverty is extremely limited, but available data indicate that 43 percent of urban residents are poor (defined as a food intake of fewer than 2,122 kcal per day) and 23 percent are extremely poor (defined as an intake of fewer than 1,805 kcal per day). The problems of increasing urban poverty are enormous and thus, identifying a poverty reduction strategy and viable mechanism for implementation presents a daunting challenge for us. As it remains closest to the people, urban local government has a crucial role and responsibility in addressing the sustainable urbanisation agenda including adequate shelter, security of tenure, safe water, clean environment, health, education, nutrition, employment, and public safety. Local urban government can best understand and reflect the needs and priorities, and monitor local trends and emerging issues. However, the urban local government system in Bangladesh has remained in a very sorry state over the years. There is no denying the fact that in spite of obstacles towards a vibrant local government system, the country has made some considerable progress in rural local government, especially union parishads. The visible side is that elected local councils are demanding a stronger local government system, while civil society, public policy groups and NGOs are working actively to improve local government. But such activity is mostly limited within rural local government, specifically, around union parishads. Considering current trends of urbanisation , we need a major policy shift to urban local governance. Present situation and practices But the present municipalisation process of the country cannot cope effectively with the issues related to rapid urbanisation. Inherently, pourashavas suffer from the acute shortage of resources, which is the root cause for low-level municipal services. For resources, the pourashava depends on government grants. But this causes many problems due to the age-old procedure of grant distribution and projects remaining half-finished due to shortage of funds.

The hindering factors towards the successful performance of the country's pourashavas are illustrated in the following categories: Until a recently promulgated circular, there were no job descriptions of pourashava staff except for the chief executive officer and medical officer. The present level of staff training, managerial training and auditing and accounting capacity of the staff are minimal. In many cases it has been found that the staff has no minimum knowledge or skills in general management, even at the basic level of filing important memos and circulars. Pourashava executives report that in very few cases has the National Institute of Local Government or local government division taken initiatives for skill and capacity development of the staff. It is noted that the salary and allowances of locally elected officials are also very low. Pourashava members are also largely ineffective in addressing various local needs, coordinating development initiatives by GO/NGOs, restoring law and order and representing the local interests to higher forums. Ineffective statutory and development function: Pourashavas carry out their prescribed functions under the administrative control and direction of the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives. As such, much time is spent in receiving approvals from the ministry for annual budgets, development projects, recruitment of staff, etc. There should, by law, be separate standing committees to deal with health, education, water and sanitation, social security, women and children affairs, infrastructure, legal and financial areas of pourashava operations. However, these committees rarely exist in reality. In one of the northern district pourashavas, nine standing committees were found on paper but not in action. Understandably, this weakens and limits the service delivery capacity of pourashavas. Committees that are operational are often formed and work without following the guidelines they are supposed to follow. Poor participation, transparency & accountability: Lack of transparency, mismanagement, corruption, and inefficiency in financial management by pourashavas further marginalises the poor and disadvantaged. Similarly, the budget preparation system of pourashavas, being completely outdated, is non-transparent and full of loopholes. The basic statistical methods and patterns are not understood for forecasting future income and expenditure. Neither the ward commissioner nor the general public is consulted in the budget's preparatory stage. Rather, the pourashava members take into consideration some favoured projects and the interests of powerful lobbying groups. The general population is not aware of the roles and responsibil-ities of their pourashavas. Schemes implemented by pourashavas are never selected by involving the community. But participation and transparency are not only absent in the context of the community but also within the pourashava bodies themselves. In most cases, the chairman is the only person who makes decisions, and usually does so without sufficient involvement of the other members. However, the situation is slightly better in the case of donor and NGO funded development projects where, in order to meet the funding conditions, pourashavas must maintain a higher level of transparency and people's participation at all stages of implementation. Weak resource mobilisation status and financial management: The weak foundation in terms of human resources, materials and finance of the municipalities is one of the main reasons for non-performance of the pourashava. One of the important consequences of low tax revenue is the institutional weakness of tax administration in the pourashavas. In addition, there is a lack of basic skills in tax administration at the municipal level. A study conducted on 26 pourashavas and 4 city corporations by the World Bank leads to the following results: The main source of revenue income is holding tax. But government has in the past circulated new rules and regulations regarding tax breaks, which are contradictory to the Pourashava Ordinance 1977 and have contributed to a reduction of income. It is stated in the industrial policy of the Board of Investment that export-oriented industries are exempted from paying local taxes such as municipal taxes. In 1999, a circular from the Prime Minister's Secretariat also mentioned that 100 percent export-oriented industries would be exempted from all kinds of municipal taxes. Due to these two circulars, tax revenue of pourashavas has been greatly squeezed. For instance, there are about 338 small and big factories for garments, jute, pharmaceuticals and textiles among others in the Tongi Pourashava area. However, the pourashava is not empowered to collect taxes from any of these due to stated circulars. Moreover, elected local bodies are reluctant to collect tax from city dwellers for reasons of local politics and pandering to public opinion. Reportedly, most ward commissioners and chairmen stand by tax defaulters to attain popularity. Delegation of power: The existing ordinance gives the elected pourashava chairman all executive powers, including the power to delegate to others. In practice, there is a minimal level of delegation of powers by the executives. The roles assigned to the council and the commissioners are too vague, and the committee structures of the municipal councils do not function properly. An important element of government accountability is the oversight and control of the executive branch of the municipal authority by the council. This type of accountability is particularly non-existent at the urban local government levels in

Bangladesh. In particular, the current structure of municipal governance mixes executive and legislative powers by making the chairman the head of the municipal council. Thus, the chairman can overrule the majority of the council's decisions. The municipal council needs to play a leading role in budgetary decisions and overseeing municipal finances and operations. No town planning: Unfortunately, urban planning has never received adequate attention from planners and policy makers in Bangladesh. As a result, preparation and implementation of a city master plan and development plans are assigned to pourashavas as an optional function. But pourashavas seldom prepare master or annual development plans. Instead, they generally prepare a list of projects, which neither evolves out of community consultation nor reflects the community's felt need. It is also noted that there is no functional database for local government, which might help guide overall planning and development, so, planning activities take place without benefit of key information. The creation of posts for pourashava-level town planners is extremely urgent in view of the deteriorating environmental conditions in the towns and city's of Bangladesh. Role of pourashava in poverty alleviation: Unlike rural areas where local bodies are directly involved in poverty alleviation programes (e.g. RMP, VFG, Food for Work etc.) urban local government is not mandated to play a role in urban poverty alleviation. One example of such rural-oriented thinking can be seen in the secondary education sub-sector, in which the Female Secondary School Assistance Programme and the Monthly Pay Order system have done much to boost access, particularly for rural girls, but have failed to address the realities of the urban context. A 2007 World Bank report highlights the severe deterioration of quality of life in urban areas, which jeopardises the efforts of Bangladesh in achieving her Millenium Development Goal targets. It proposes to tackle the problems of urban residents directly through a range of measures, including improved incentives for poor children in metropolitan areas to go to schools, replication of effective water and sanitation service delivery models, and reduction of air pollution. These problems must be addressed through ways that increase the accountability of urban government officials. Autonomy of pourashava: Pourashavas are autonomous and independent in many ways, but in reality, their effective autonomy is limited. The administrative operations of urban local governments are subject to the rulings of the central government. In practice, pourashavas have limited flexibility in the daily implementation and management of their budgets. Revised budgets require approval of the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development and Cooperatives, a process which is time consuming. Moreover, the current legal framework for pourashavas does not provide scope for considering alternative approaches to service delivery, through privatisation or the participation of NGOs. Alternative options must be considered for improving the provision of municipal services and for achieving efficient resource allocations. Political will and municipal reform initiatives A thorough review of governance and management aspects of municipalities suggests that there is a patron-client relationship between government and local bodies which hinders the process of staff recruitment and development of skilled staff, timely delivery of services, and effective implementation of development projects.

The issue of urban local governance presents a peculiar and frustrating paradox in Bangladesh. The most crippling problem faced by the urban local government is the absence of a sense of urgency to reform it. Unlike union parishads, there is a perception gap to view the municipal institution as a facilitator of poverty alleviation. It is seen that the government lacks a clear strategy relating to the pourashava problems. However, in 1990, an attempt was made to reform the existing urban local government institutions, i.e., the pourashavas of Bangladesh, by appointing the "Poura Commission." The main objectives of the commission were to: 1) identify reasons as to why city corporations/pourashavas could not provide adequate services to the urban people, and 2) offer recommendations on the measures to be undertaken by the local bodies to meet various increasing demands of urban people, keeping in view the country's existing socio-economic conditions. The Poura Commission provided several recommendations on the aspects of structure and composition of urban local bodies, central-local government relationship, finance, planning, municipal services and housing and land policies. The commission also recommended formulating an appropriate slum development policy with the participation of slum dwellers. Similarly, in 1997 the Local Government Reform Commission presented a report, with many recommendations about the decentralisation of local government institutions. But, unfortunately, not much has been done on this commission report so far. The current Bangladesh PRSP indicates the need for a reformulation of the decentralisation agenda and an agenda for promoting local governance. Key priorities in this reformulated agenda include the course of action to lay the groundwork for a comprehensive legislation on local government. At present, there is a plethora of laws and circulars, often outdated and self contradictory, which govern existing local governments. These need to be streamlined into a comprehensive act.

As the current caretaker govern-ment is committed to bringing meaningful changes in many sectors, a real need for undertaking urban reforms becomes pressing. Already, a high-powered committee on local government reform has been created to formulate the recommendations and find a way forward. There is, therefore, an urgent need to review the findings and recommendations of the Poura Commission 1990 and to highlight issues of the pourashavas to enhance service delivery systems of these urban local government bodies. We hope the local government commission will make some sweeping changes in the laws and policies of the local government system both in rural and in urban Bangladesh. Ashekur Rahman is currently working with Care Bangladesh as Deputy Urban Program Coordinator. Views expressed in this article are his own.

|