Inside

|

Food Fight Mamun Rashid examines the risks and effects of high and volatile food prices Food prices have surged over the past few years and have increased by about 40% since We all know price increase usually results from increased demand or reduced supply. The surge in global food prices is not an exception. It is once again a story of supply and demand. However, short-term pressures are mostly on the demand side of the equation and a confluence of factors has led to price hikes. However, before going into the demand drivers, let us look at the supply side constraints. First of all, high fuel prices have contributed directly to soaring food prices, as well as further undermining the livelihoods of the poor through overall inflation. While grain prices have almost doubled over the past year and a half, oil prices have almost tripled over the same period. This has had a direct impact on farm production costs (cultivation, processing, refrigeration, shipping and distribution), fertiliser prices (200% to 300% increases), as well as diesel and transport costs -- all of which contributed to continued high food prices. Further, productivity growth in agriculture has festered as a result of low levels of investment in infrastructure and R&D, and the deterioration of institutions and poor conservation practices. Continuing low prices at the farm gate for output coupled with general subsidies for consumption and rising input prices because of increased oil/fuel costs have damaged incentives for farmers. The main reasons behind why Bangladesh was not affected as badly as expected were a gradual rise in food prices during last several years, and the present government's drive to shift the terms of trade towards rural Bangladesh by increasing the procurement price. Increased inwards remittances from the oil rich countries and disbursement of MFI loans also contributed significantly. Commercial property development and urbanisation have taken over farm land and have increased competition for supplies of irrigation water. Irrigation accounts for 85% of water withdrawals in developing countries, and farming is completely based on the availability of these huge quantities of low-cost water. Supply disruption due to adverse weather conditions in key exporting countries also contributed to global food shortage. If we focus on the demand drivers there are a number of factors, some of them are long-term in nature. Recently, US president George Bush linked the higher food prices to higher demand in China and India. Strong economic growth is continuing in the emerging countries. Hence, more and more people are crossing into higher income threshold and there is a steep rise of the middle class income group in the emerging economies. The middle class is buying more food higher up the food chain and the apparent improvement in the diets of people, particularly in populous emerging Asia, have underpinned rising demand for grains (dairy and livestock products are highly grain intensive). Recently, a World Bank report which stated that rapid income growth in developing countries had not led to large increases in global grain consumption and was not a major factor responsible for the large price increases of global food created much controversy in the international arena. The report estimated that higher energy and fertiliser prices accounted for an increase of only 15%, while production of bio-fuels in the US and EU countries were responsible for a 75% jump in food prices over that period. Bio-fuels have distorted food markets in the following ways: Moreover, many countries started imposing food export controls by agricultural export bans, high export tariffs, and price controls to protect local farmers and consumers, which further distorted regional and global food markets. Countries in Asia (India, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia) and South America (Argentina, Brazil) clamped down on exports or banned them, mostly at the behest of their panic-stricken leaders worried about inflation.

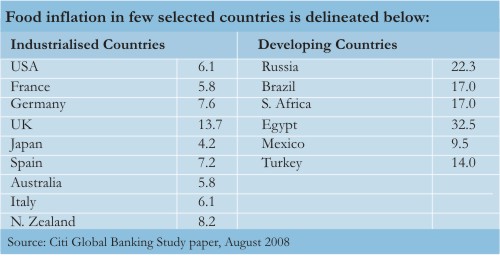

What can be the economic impact of high food prices? (Refer to tables above.) Higher global prices translate to rising inflation. The inflationary impact of rising commodity prices varies, depending on the share of the consumption basket dedicated to food purchases, and how much is passed through to other goods and wages. The impact is more heavily felt in developing countries -- given that a greater share of income goes toward food purchase. In Asia, the impact will be even more as many Asian nations are net importers of food and oil and food carries a large weight in consumer baskets. GDP growth is expected to decline since higher prices will reduce consumption. The impact of higher food prices is affecting the external balances of some of the poorest food-importing countries. The effects are being exacerbated by high oil prices. Targeted subsidy programs may be implemented to alleviate inflationary impacts on the poor in the short term. However, countries seeking to soften the impact of food price increases through subsidies must cope with increased fiscal pressure. For example: as per Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates, in the Philippines where most of subsidised rice is imported, a 50% increase in rice import prices leads to a 329% increase in total subsidy cost. Other distributional implications of high food prices include rising poverty levels in food-import dependant countries, and declining living standards for the poor, which is also applicable for the industrialised world.

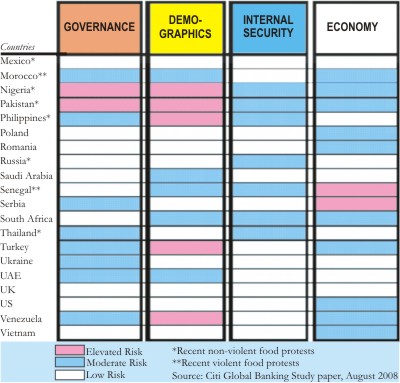

After 20 years of progress toward more open markets, higher food prices may strengthen support for protectionist policies and anti-globalisation sentiment. However, this will depend on a country's level of development. For example, export bans/restrictions may increase volatility, harm import-dependent trading partners, stimulate cartel formation, undermine trust and encourage protectionism. Price control is likely to reduce farmers' incentives to produce more food. Increased subsidies will trigger high fiscal costs and the system will be inefficient. Food insecurity can be a powerful trigger for aggression. Rising food insecurity has the potential to spark resentment. Soaring food prices are a catalyst for, but not a cause of, political risk. A country's vulnerability to the shock of high food prices can be assessed by considering a range of political and economic factors (delineated in the table below). Countries experiencing fast growth and weak governance/institutions often show more elevated risk. Countries with weak governance are most at risk of demonstrations that can turn into riots, or worse. Food insecurity can lead to rapidly rising inflation, declining living standards, weak institutions, well-organised political opposition and political conflict. In such cases strong GDP growth, higher contribution of agriculture to GDP, large trade surplus, and creation of effective security forces can be the stabilising factors. In short, a country's governance (strength of governance/government effectiveness), demographics (growth of urban population, percentage of adult population), internal security (civil conflict, violence, strength of military), and economy (trade balance, inflation, GDP growth, fiscal balance, production/export of key staple goods/crops) determine a country's capacity to respond to the food crisis. The political implications of the food crisis will also depend on a country's economic growth and structure. (Refer to table on same page). While the emerging markets and industrial nations may suffer from risk of decline in living standards or increased perception of income inequality; the least developed countries may experience large scale famine, poverty to a great extent, riots, protests, demonstrations or coups. It is reported by World Food Program (WFP) that more than 70 countries have experienced food-related riots. The impact of high food prices also varies by region. African countries are the most severely affected by rising food prices, given already-high poverty levels and dependence on food imports. UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation has identified 36 countries, which are deemed "in crisis" in terms of food security. Out of those 36 countries, 21 are African. About 33% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa and 16% in West Africa is considered "malnourished." Around 2.9 million hunger-related deaths are reported per year in the region. In Mexico, Central and South America region, a high level of income inequality prevails, which can be exacerbated further by income erosion due to higher food prices. While some areas of Latin America could potentially benefit from higher food prices through increased production, the region's relatively higher logistics costs (1832% of product value versus < 9% for OECD countries) may limit their ability to capitalise on price increases.

On the other hand, Eastern Europe and Central Asia are major grain-producing regions. Several of the world's biggest beneficiaries of high food prices, like Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Russia, are concentrated in this region. The UN suggests that 13 million hectares of arable land in this region could return to production, with no major environmental cost. The region is also still in the midst of its transition from communism, and moves toward state intervention in grain markets and the re-imposition of subsidies are emerging. However, despite rapid growth in living standards, many could relapse into poverty. Asian consumers have been hit particularly hard by high food prices. Recent improvements in standards of living and rising incomes in Asia have, at the same time, driven prices higher in the region and around the world. Higher prices will disproportionately lower real income in parts of Asia, especially in Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines and Vietnam, where food consumes about 50% of family expenditures. The South Asian region has not been immune to the global price rise phenomenon. Bangladesh, a net importer of food grains, has been seriously affected by food price shocks, driven by higher international prices and domestic production shortfall following successive natural disasters. Although upward price pressures somewhat eased by early May 2008, the price of rice and wheat in the domestic market is still 50% higher than in FY2007. The government's selling price under open market sale was Tk 28 per kg as against the import cost of Tk 32 per kg. Since FY1991, food-grain production rose by 2.5% or 0.5 million tons a year. But food security remains elusive, particularly in years when production is affected by natural disasters. The food deficit remains sizeable, estimated at 340,000 tons in FY2008. Although larger imports more than offset the food-grain production shortfall following the natural disasters, prices in the domestic market soared because of higher international prices. Despite a bumper boro crop, risks of a supply shortage are possible if the next aman and boro crops are affected by natural disasters or other factors. To deal with any possible food shortages in the coming months or later, the government was planning to build a stock of about 2 million tons of food grains under the public food grain distribution system.

There are also business implications of food insecurity. Food-related industries have varied vulnerability to high and volatile food prices depending on the importance of food commodity prices to the overall business. The elasticity of demand for products is a factor in determining the degree to which the companies can pass through higher prices. For example, during crisis the restaurants, food distributors and the related industries will be more vulnerable in terms of costs and demand since due to higher prices customers will shift from eating out to dining at home. Companies may adopt a number of measures to counter higher and volatile input prices. In the short-term, companies may focus to the degree and timing of passing on higher costs to end consumers. The other options can be cutting costs or shifting of product quality mix, etc. However, the range of options varies on the nature of the industry. In the medium term, companies are expected to hedge commodity prices, redesign production process or product mix. Consolidations, mergers and acquisitions are also likely options in the medium term. In the long term, companies may also find vertical integration and renegotiated agreements with suppliers and distributors as viable options. In capital markets, stock prices in certain industry sub-sectors can be significantly influenced by volatile food prices. With rising commodity price volatility, correlation between range of commodities and their impact on a company's share price have also increased over the past years. Price volatility of wheat was about 27% between 2004 and 2007 and price volatility of sugar was 22% during the same period. In past 12 months, price volatility of wheat increased to 39.2% (12% increases) and for sugar the volatility rose to 39.8% (17.8% increase). Safety nets should be created by government to address the most immediate food, nutrition, and production needs in susceptible economies. Safety nets have broad common objectives. They can vary in the form in which assistance is provided and the behaviour they are intended to support. The most common forms are in-kind, vouchers -- including food stamps, fertiliser vouchers, and cash. In a poorly functioning economy, it may be more effective and less costly to provide food or inputs directly to families. Where markets are in-place but private suppliers are unwilling to invest in distribution infrastructure without some assurance of demand, voucher-based systems can be highly effective in providing incentives for greater private investment. In countries and regions where markets and banking systems are operating reasonably well with an outreach to people even in remote areas, cash transfers may be the preferred option given their generally lower administrative costs.

The World Bank has estimated that there are an estimated 982 million poor people in developing countries who live on $1 a day or less (World Bank, Understanding Poverty, Chen 2004). As per FAO estimation, there are 850 million undernourished people. World Hunger Facts, 2008 mentions that extreme poverty remains an alarming problem in the world's developing regions, although, despite the advances made in the 1990s till now, which reduced "dollar a day" poverty from (an estimated) 1.23 billion people to 982 million in 2004, a reduction of 20 percent over the period. Progress in poverty reduction has been concentrated in Asia, and especially, East Asia, with the major improvement occurring in China. In sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people in extreme poverty has increased. The way out of the crisis will not be easy, since the dramatic food price spiral has numerous causes. It is vital to ensure early emergency reaction to food shortage episodes, including capacity to mobilise food quickly and cheaply to the most affected areas of the world. Efforts to increase funding and improve coordination between governmental agencies responsible for food assistance are all excellent initiatives that have already been announced by many governments including Bangladesh in recent months. Policies that stimulate production of bio-fuels have taken away lands from food production. More knowledge and study on the overall contribution of bio-fuels to sustainable development is absolutely essential.

Export restrictions in food-exporting countries are a detrimental reaction to food price increases. Export restrictions also highlight the weakness of the global agricultural trading regime. We need a system to ensure that both imports and exports remain free to flow in all times. A positive fallout of the current crisis is to bring agriculture back into focus. Decades of neglect of agriculture have heightened our exposure to food crises and contributed to increasing the number of people who go hungry in the world. To do so, resources alone will not suffice if they are not properly directed to raising agricultural productivity in developing countries. To counter the challenges posed by the current food crises requires joint action by various members of the international community. Wealthy and developed nations should take the leadership role. In the short run, Japan and China should allow their stocks of rice to be shared with those in need, and the United States should abolish origin requirements on food aid. Over the medium run, we need collective action in the WTO to eliminate distortions in agriculture and agricultural trade, including the substitution of US and EU bio-fuel programs with green policies. In the long term, we need to rally resources and revitalise institutions to boost agricultural research and productivity in developing countries, including Bangladesh. Mamun Rashid is a banker and economic analyst. The writer is grateful to Dr. Mahabub Hossain from Brac, Dr. Zahid Hussain from the World Bank, and Suraiya Zahan from Citibank, for their intellectual support and guidance in this regard. Photos: AFP |

2006. The dramatic rise in global food prices is not the result of any specific climatic shock or emergency. These are cumulative effects of long-term trends, including supply and demand dynamics. Although prices have declined somewhat from their recent peaks, several structural factors are expected to keep them relatively high and more volatile than in the past.

2006. The dramatic rise in global food prices is not the result of any specific climatic shock or emergency. These are cumulative effects of long-term trends, including supply and demand dynamics. Although prices have declined somewhat from their recent peaks, several structural factors are expected to keep them relatively high and more volatile than in the past.  Panic buying by importing countries, as well as by consumers and traders, caused further price increases. World trade in rice is extremely small relative to production/consumption -- over 90% of rice is produced and consumed in Asia. Only a few countries supply rice to the international market. This has made international rice prices volatile. Down the supply chain, farmers and producers are hoarding food to delay its sale. Hence, we are experiencing a sort of "prisoner's dilemma" known in game theory: Individuals (and individual countries) are protecting only their own interests -- "defecting" rather than cooperating -- since supplies has become more precious.

Panic buying by importing countries, as well as by consumers and traders, caused further price increases. World trade in rice is extremely small relative to production/consumption -- over 90% of rice is produced and consumed in Asia. Only a few countries supply rice to the international market. This has made international rice prices volatile. Down the supply chain, farmers and producers are hoarding food to delay its sale. Hence, we are experiencing a sort of "prisoner's dilemma" known in game theory: Individuals (and individual countries) are protecting only their own interests -- "defecting" rather than cooperating -- since supplies has become more precious.

In summary, the effects of the food crisis will reduce incentives for reform, undermine business environment, increase political risks, and induce policy changes towards export restrictions and subsidies. Government takeovers of food production or distribution could occur where food stocks are diminishing. Foreign governments' efforts to secure future food supplies by buying land and investing in agricultural production in the developing world could generate repercussions. Political risk premium could also rise in some countries, if protests, riots, increased demands by the public and other pressures contribute to government policy reactions that undermine markets. The operating environment for business in many countries could become more erratic, given the constellation of emerging risks. Protectionism and anti-globalisation sentiment could increase as well. There will be enhanced prospects for investing in agricultural production and technology. Food producing nations would be more benefited by being part of the solution and could see more inward investment. Corporations and policy-makers should be prepared to respond to high and volatile prices and develop strategies to mitigate the risks.

In summary, the effects of the food crisis will reduce incentives for reform, undermine business environment, increase political risks, and induce policy changes towards export restrictions and subsidies. Government takeovers of food production or distribution could occur where food stocks are diminishing. Foreign governments' efforts to secure future food supplies by buying land and investing in agricultural production in the developing world could generate repercussions. Political risk premium could also rise in some countries, if protests, riots, increased demands by the public and other pressures contribute to government policy reactions that undermine markets. The operating environment for business in many countries could become more erratic, given the constellation of emerging risks. Protectionism and anti-globalisation sentiment could increase as well. There will be enhanced prospects for investing in agricultural production and technology. Food producing nations would be more benefited by being part of the solution and could see more inward investment. Corporations and policy-makers should be prepared to respond to high and volatile prices and develop strategies to mitigate the risks.