Inside

|

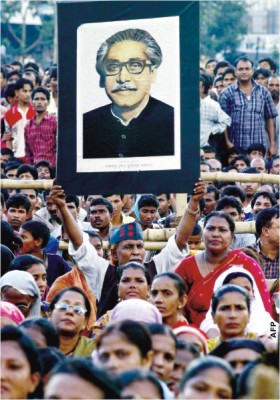

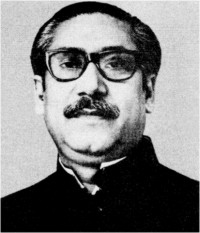

Reflections on a Murder Tariq Karim ponders what Bangabandhu's assasination on August 15, 1975 means in today's society In every nation's history, there comes a leader who stands head and shoulders above all others, who serves to define the ethos and essence of that nation. No one can ever doubt or contest that for Bangladesh, that leader was Bangabandhu, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Without Bangabandhu's appearance, without his uncompromising determination and courage -- let us face it and acknowledge it -- there would have been no Bangladesh. Just as how India's independence struggle would not have been defined and chartered in the way it had been without Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Or, how South Africa's liberation struggle and long walk to freedom was led by Nelson Rohlilala Mandela. And so, as Gandhi is rightly identified and revered as the father of modern India's nationhood, and as Mandela is universally acknowledged and respected as the father of post-colonial South Africa, Bangabandhu was undeniably the father of the new nation of Bangladesh. Yet, one cannot help but be troubled by the fact that the nation remained largely silent when the killers who murdered Bangabandhu and almost his entire family in cold blood 33 years ago were not only indemnified from standing trial for their heinous crime, but were also rewarded with lucrative diplomatic assignments abroad and protected by state security. August 15, 1975 remains a shameful black spot in our nation's history that no perfumed detergent from anywhere will ever erase easily. The fact that there was no official commemoration or national mourning of this tragic date and event over the last six years will haunt the conscience of Bangalees everywhere who take immense pride in their nationhood. It was only after the Awami League government of Sheikh Hasina took the initiative that efforts were made by the state to bring the killers of Bangabandhu to justice. An agreement on extradition was signed with the United States government shortly after I took office as Bangladesh's ambassador to the United States in April 2001. Although this agreement was ratified by Bangladesh immediately on account of the relative simplicity of our ratification procedures, the US ratification procedures were not completed until late October of that same year. However, by then, there was a new government in Bangladesh. At a reception I hosted for the new foreign minister of Bangladesh in November 2001 (who later became president for a short period of time), an official of the US Justice Department, who participated in the final round of negotiations that led to the signing of the agreement, drew me aside and asked me: "Mr. Ambassador, we are ready now to extradite the people wanted by Bangladesh for the assassination of your president in 1975, but we have not yet received any request for the same. Do you know why?" I had wished at that moment that the earth would swallow me and cloak my sense of shame. I commend the present government in Bangladesh for having restored the comm-emoration of August 15 as National Mourning Day, following the High Court ruling. Indeed, I commend it on its many other noteworthy achievements such as getting the core institutions of the state, that had been so grievously injured and damaged, like the Election Commission, the Public Service Commission and the Anti-Corruption Commission, back on their feet.

I commend it for finally having separated the judiciary from the executive and setting this hallowed and all-important institution of the state back on the path to functioning in a truly independent manner. Given the nature that our practice of politics had mutated into, these are all tasks that only a government of this nature could have done, and they have done it well. But I still have grave misgivings and am still deeply troubled by this interregnum government's over-zealous and lopsided agenda of "wiping out corruption." In embarking on this, they have strayed into an arena that is beyond their ken and capacity, and rightly belongs within the jurisdiction of an elected government. I am convinced that the manner in which they set about it was wrong and self-defeating, because they have put the cart before the horse. The so-called Truth Commission is a travesty of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that I had in mind and advocated earlier, in the page of The Daily Star and elsewhere -- and I will state why I feel this way. The crimes of corruption that so preoccupy the present regime, as indeed they have horrified the entire nation, pale in significance when compared with the reprehensible crimes of the murders of the father of our nation and almost his entire family, of state leaders who were supposedly in protective custody in jail, and countless other killings and acts of violence crimes committed over the past three decades that were virtually indemnified from prosecution by the state. And those crimes in turn, pale beyond any significance when compared to the most heinous crimes committed against humanity during the period leading to our liberation, crimes which we all appeared to have turned a blind eye to for the last 38 years. In the ultimate analysis, the entire nation is deemed as culpable for having acquiesced to this state of affairs as the administrations that actively presided over this malfeasance. A nation's consolidation can only take place on the bedrock of justice and a rule of law that is Similarly, in a converse and reverse mirror-image process, each criminal act that is ignored, condoned and indemnified, serves to give sanction to every subsequent criminal act, irrespective of its scope and dimension.This is the inevitable yin-and-yang of any web of societal mores. And this continued ignorance of the now long dossier of horrendous crimes committed in the past has resulted in our culture of acquiescence and impunity today that defines us to ourselves and shamefully identifies us to the rest of the world. Sometimes, I wonder what Bangabandhu would think if he were to somehow miraculously return today and witness to what depths his dreams of Sonar Bangla have been consigned to by the people he so loved. I imagine he would call out in his booming, resonant voice, something to this effect: Tariq Karim is former Ambassador of Bangladesh to the United States. He currently teaches as Adjunct Faculty at the University of Maryland, George Washington University and the Virginia International University. |

applicable in equal measure to all persons in that society, irrespective of their status. Without it, the foundations of that nation will always be brittle. This system of justice flows not only from a nation's constitution, but also from the cumulative judicial precedents that accrue over a period of time. Each new precedent established in rule making and administering justice serves to reinforce and further strengthen this holistic system of law and justice.

applicable in equal measure to all persons in that society, irrespective of their status. Without it, the foundations of that nation will always be brittle. This system of justice flows not only from a nation's constitution, but also from the cumulative judicial precedents that accrue over a period of time. Each new precedent established in rule making and administering justice serves to reinforce and further strengthen this holistic system of law and justice.