Inside

|

Nurul Islam: Searching for Truth Fariha Karim talks about the end of a lifelong crusader against injustice The walls are scorched black, a thin film of soot covers the burnt out wreckage inside the

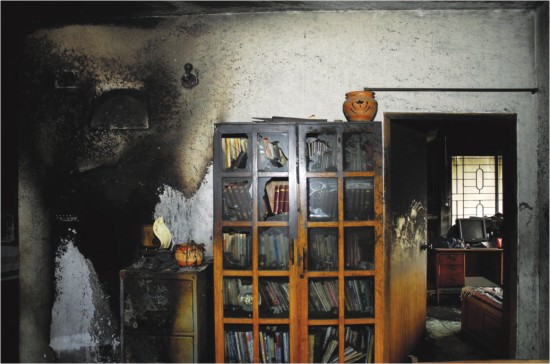

living room of Nurul Islam's former flat. A thick smell of burnt plastic hangs in the air. On the corner of the dining room table, a packet of cigarettes stubbornly sits in pristine condition, and books arranged on nearby shelves are in a near perfect state. It's a bright Thursday morning and the light is good. It pours in through the windows, bringing a strange glow to the otherwise pitch-black former family home. It's six months on from the fire, which killed Nurul Islam, a freedom fighter, Ganotantri Party president and the president of the Trade Union Kendro (TUC) in Bangladesh. The veteran left wing politician was found gasping for his life minutes after the fire broke out during the early hours of December 3 last year, his only son, Tamohar, killed before he could reach the front door. Moutushi Islam, Nurul Islam's only daughter, is back in Dhaka on a brief visit from the States where she works. Time is short, but I wanted to meet her and her mother, Ruby Rahman, since elected as an MP, to talk about the horrific events, to talk about how they are able to carry on afterwards, and find out why they suspect Nurul Islam, the country's foremost trade union leader, was the target of a politically motivated killing and not the victim of an "accident" as ruled in a report.

The first thing that strikes me is that time has healed no wounds for Moutushi. Standing among the charred debris of the fourth floor flat, she still cannot say they are dead. "I refuse to accept this fact," she says, "I can't say that they 'died'. I say 'ora ekhane ar nai' -- they are no longer here." Her description reminds me of the "disappeared," in Bangladesh, but also historically in South America. The Argentinian photographer Marcelo Brodsky has spent the last 10 years working on the "disappearances" of the dictatorship during the 1970s in the country's Dirty War. He describes how they refer to victims as "missing" -- always in the present tense, because their situation has never been resolved, they still don't know what happened. For Moutushi it is a clear-cut case of the kind of political violence that reportedly claimed at least 1,300 lives in Bangladesh between 2001 to 2006 -- the death of a popular political activist in mysterious circumstances in the run up to the election. The following attempt to record the death as 'accident' and subsequent attempts to hush up further investigation, to ensure the initial report is the only verdict, urging people to "forget" and move on. The nation was in shock when news of the fire first broke. Suspicions ran wild that Tamohar and Nurul Islam, due to stand on an Awami League ticket in the 14-party alliance, were the victims of sabotage. Using his final few breaths, Nurul Islam told television channels he was being threatened -- since confirmed by party and trade union colleagues -- by people urging him to "come to the path of Allah." In a series of heartbreaking interviews, he used his last available strength to loudly say: "It is a conspiracy to kill me. They have been threatening me for a long time so I can't stand for election. They won't let me live." Under the constant glare of rolling TV crews, he was visited at Dhaka Medical College Hospital by now Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and opposition leader Khaleda Zia. He had suffered 40 per cent burns, and surgeons operated on his windpipe. But being burned alive was too much for his body to cope with, on top of his diabetes and kidney problems. He died after being transferred to the Combined Military Hospital where, visiting friends had said, he should have been taken earlier so he could have been treated in intensive care. At the time, Sheikh Hasina told reporters: "It should be properly investigated whether Nurul Islam was killed in a planned way." Her colleagues, Matia Chowdhury and Abdur Razzak, added: "We cannot let the evil forces go scot-free and the killers of Nurul Islam must be brought to justice.” The following day, hundreds of supporters and well wishers flocked to the Shahid Minar to pay their last respects, showering flowers on their coffin before Tamohar and Nurul Islam were buried at the Martyred Intellectuals Graveyard in Mirpur. Tributes poured into every newspaper, mourning the loss of one of the country's greatest potential leaders. A cross party collection of politicians, trade union members, International Labour Organisation representatives, television personalities and activists joined growing calls for an investigation, saying it was the greatest honour they could give him.

Almost immediately, a joint team of Detective Branch (DB) of police, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) and Mohammadpur Thana launched an investigation into the incident. But by December 7, fire service director Brigadier General Abu Nayeem Mohammed Shahidullah claimed their investigation did not find signs of combustibles, explosives, or suspicious materials. He said the fire was caused by "accident," by a short circuit in the fridge. The finding was officially recorded and sent to the home ministry. But the report, according to family, former colleagues and friends, was demonstrably flawed. It claimed there had been an explosion from the gas cylinder in the fridge. Yet a television report showed the fridge compressor perfectly intact. Flammable items within striking distance -- cigarettes, books, papers, plastic food covers -- hadn't been touched by the flames. Eyewitnesses told of intense heat and noxious smoke, but not fire. And more perplexingly, the fridge which "caught fire" was disused and had been "unplugged for three years," according to the family. They also fear the report, which they have never seen, leaves further unanswered questions, for example the threats and phone records. These were never raised. Investigators also failed to examine the very reason Nurul Islam was in Dhaka at all. Earlier that day, he was travelling to the Noakhali constituency he was going to stand in, but turned back after a former trusted associate told him his name was on a bankruptcy list, declaring him unfit to stand for election. He was also told a letter, mysteriously from the Sonali Bank in Cox's Bazaar -- with which he had never had any dealings -- said he had taken 8 lakh taka and he was being investigated. He was fatally advised to come back, and planned to release a press statement the following morning with evidence of how the letter and list was clearly a stitch up. Now, Moutushi tells me how she looks back to the last conversation she had with her father, two hours before the fire, and in hindsight, was given warning, but not nearly enough. She was always aware that as a political figure in Bangladesh, her father was at greater risk. But she never imagined she would lose her father so soon. They talked for the first time about the threats he had been receiving. She asked him if he was sure he still wanted to run for election. She says: "He told me, 'don't you want me to work for my people? This is what I have been doing all my life. This is my last chance to talk about them, voice their needs, in parliament'." She continues: "My father was very vocal. He wasn't scared of death, or of the truth. He accepted that unwanted things could happen in his life. He was very brave, even more than we knew. I didn't know the context in late November, but I was still feeling scared, I thought there might be a hazard. But I wasn't expecting this -- that both of them would be killed. Neither of us realised the final blow was knocking at the door."

Nurul Islam's son, Tamohar Islam, affectionately known as Puchi was a musician and writer who wrote for international publications, composing songs and commentaries on music while working as an IT professional. "He was witty and friendly," Moutushi says. "He was brilliant. He could just make up funny poems on the spot. He was talented. He was always the centre of attention, and always kind, especially to his friends. His former boss in the States, who is 62, still comes to me and cries about his death."

Moutushi and her friends had been preparing a surprise birthday party for Ruby, who was visiting her on a writer's fellowship as part of her work as a visiting professor at the University of Iowa, when her cousin called and gave her the news. There had been a fire at their flat while her brother and father were asleep. Puchi had died. "I can't stop thinking about that those newspaper headlines that said 'he was burnt alive'," Moutushi says. On the plane on the way back, she suffered in silence knowing her brother had died, unable to break the news to Ruby. By the time she arrived at Zia International Airport, she was given the final blow. Her uncle told her: "Baba o nai." "I think my life stopped there," Moutushi says. "I felt this was just a nightmare. I still sometimes think that, it's just a long nightmare. It's not happening to my house, to my life. How could anybody burn two people in a family?" But her life hasn't stopped, just changed beyond all recognition. Now, she is determined to ensure the report is not the only historical verdict on the deaths. She can't bring them back, but she can try and ensure no stone is left unturned to establish how and why they died. In this, she is backed by family and friends, her father's colleagues in the 14-party alliance, and comrades in the trade union movement who have all fought for the case to be investigated. Following an order by home minister Sahara Khatun, the case has been kept open and is with CID. They are investigating the threats, the mobile phone records, and the letter trail, according to the investigating officer. Moutushi and Ruby are also conducting their own door-to-door enquiries. Moutushi said: "Whoever planned the killing thought it out very well and was careful to make it look like an accident. But there are too many discrepancies. It is also strange it happened when my mother wasn't in the country, so the house was more unguarded. There are too many co-incidences to say it is just an accident. If they say it was an accident, they have to justify and prove it, which they haven't yet done. Just saying so isn't enough." Looking back to Bangladesh's past, if she is able to prove that her father and brother did not die by accident, it will be a rare historical moment. Political killings in Bangladesh have a poor track record of being truly solved, beyond all reasonable doubt. As well as the hundreds of deaths, more than 35,000 have been injured in acts of political violence, often by henchmen armed with anything from pistols to bamboo sticks. Activists are routinely abducted. But it is now feared a culture of impunity has overtaken attempts for justice, beginning with the assassination of independence leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1975, killed with 21 members of his family. For two decades the killers were shielded under the Indemnity Ordinance act until it was repealed in 1996, allowing further killings to continue in the absence of any punishment, which could have set a precedent. While 12 people were then handed the death sentence, the government is still working with foreign ministers in the US and other countries to have remaining "fugitive killers" extradited. Meanwhile murders of other political figures, such as former finance minister Shah AMS Kibria, killed in a grenade attack in January 2005, are still unsolved. Sheikh Hasina herself survived an assassination attempt the previous year, during a grenade attack, which left 23 dead and 200 injured. During the attack, both legs were blown off veteran Awami League politician, Ivy Rahman, who died in hospital three days later. The cases have never been concluded before the courts.

Cases, which have been brought to court, have done little to restore faith in the justice system. When, in 2004, the culprits were brought to trial for the 1975 "jail killings" -- where acting president of the government-in-exile Syed Nazrul Islam, prime minister Tajuddin Ahmed, finance minister M Mansur Ali and home minister AHM Qamruzzaman were killed inside a prison cell -- the judge cited faulty investigation. Families of victims claimed the process was a farce. In May 2004, freedom fighter and Awami League politician Ahsanullah Master was shot after a public meeting, dying in hospital hours later of profuse bleeding. While 22 people were handed the death penalty over the murder, it is feared some culprits are still on the run. Bangladesh has also witnessed the killings of leaders through coups and counter-coups, for instance Ziaur Rahman in 1981, in cases that raised further dubiety during the trial process. Others were killed in a wave of politically motivated bomb blasts in 2005. Lawyers have suggested the conviction rate in criminal cases is less than 10 per cent in Bangladesh. "I don't know if it will be different for me," Moutushi sighs, "but there is no question of giving up. It will be a very arduous journey. But anyone whose family was burnt alive would do the same thing." Now, Moutushi has made steps towards continuing her father's legacy at the Dhaka University Class Four trade union. At an emotional meeting last month, University union members were in tears while recalling Nurul Islam's memory, and pledged to build a library in his name. "I used to play in the yard of the Class Four union office as a child while my father was meeting the union members," Moutushi says. "I want to continue the hard work my father spent his life building up. He had so much support from his union colleagues, and I want to continue the relationship." Is Moutushi prepared for what will probably be her toughest fight? She says that having worked as an activist with acid burn victims and women workers on lower tiers, she knows "there will be lots of negative things, lots of failure in the process." But, she continues, "My father was a very spirited activist, he achieved a lot and he lived up to his dream. I feel that inside me. I'm not like my father at all, but I feel I can borrow his spirit to seek justice." Fariha Karim is a freelance journalist and photographer. |

Friends described Islam's family as the ideal, romantic family -- the leftwing trade unionist and his poet wife, a handsome couple who modestly brought up their musician son and activist daughter in a rented Lalmatia flat. Nurul Islam was regarded as a tireless fighter for the oppressed, as well as a great personal friend and mentor to hundreds, devoting his entire life to the causes he believed in. He joined student politics in his school days and became an activist with Bangladesh Chatro Union, later joining the Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) after completing his masters. He took a well-paid diplomatic job, which he left after three years with plans to work as a whole timer in the trade union front of the Communist Party. Ruby started working two more part time jobs in addition to her full time job to maintain the family. Islam set up the Class Four Employees Union in Dhaka, and then mobilised workers across the country under the broader labour movement, eventually becoming President of the TUC. He parted with the CPB after its division following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, joining the Ganotantri Party in 2004.

Friends described Islam's family as the ideal, romantic family -- the leftwing trade unionist and his poet wife, a handsome couple who modestly brought up their musician son and activist daughter in a rented Lalmatia flat. Nurul Islam was regarded as a tireless fighter for the oppressed, as well as a great personal friend and mentor to hundreds, devoting his entire life to the causes he believed in. He joined student politics in his school days and became an activist with Bangladesh Chatro Union, later joining the Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) after completing his masters. He took a well-paid diplomatic job, which he left after three years with plans to work as a whole timer in the trade union front of the Communist Party. Ruby started working two more part time jobs in addition to her full time job to maintain the family. Islam set up the Class Four Employees Union in Dhaka, and then mobilised workers across the country under the broader labour movement, eventually becoming President of the TUC. He parted with the CPB after its division following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991, joining the Ganotantri Party in 2004.