Inside

|

Catalysing Change Syed Akhtar Mahmood talks about improving the investment climate in Bangladesh Poverty reduction requires jobs, and productive jobs are created through investment. Unless the climate for investment is conducive, investors will not be forthcoming. This much we all understand. But how do you bring about changes in the policies, laws, regulations and institutions that shape the investment climate? Experience shows that pious intentions and open-hearted pleas are not adequate. If you want to catalyse change, you have to do much more.

The challenges of getting government going But there is hope. The same dynamics also create windows of opportunity. Those who want to catalyse change need to understand these dynamics and exploit the windows of opportunity. Mistrust of private sector but recognising that it is the engine of growth At the same time, there is widespread recognition that the economy needs to be driven by the private sector and that the socialistic approaches of the past have not borne much fruit. There is quite a bit of faith in the small entrepreneurs players. This often leads to a paternalistic attitude in government officials who feel that the government needs to take care of the small players. But like over-indulgent parents, the government often ends up doing more harm than good through such misplaced paternalism. It is important to close the perception gap between government officials and the private sector. Catalysts who wish to bring about change will have to pay attention to this. There are a number of things that can be done, such as bringing the private and public sectors together whenever possible, ensuring the participation of the private sector even in programs primarily targeted at the government, advocating public-private partnerships and disseminating knowledge about what the private sector does and what problems it faces. It is important to note that the attitude of government officials regarding the private sector is not entirely unjustified. There are indeed many cases of business people operating in ways that are not ethical. And no one is arguing that regulations should be done away with. However, government officials need to learn how to separate the wheat from the chaff. They need to know how to design and administer a regulatory system that protects societal interests while ensuring that the business people who want to play by the rules of the game have the right incentives to do so. Generally poor knowledge of PSD issues but good ability to learn quickly Yet, at all levels of government, there is a willingness to learn. I have seen from my own experience that when the officials are given the opportunity to learn, they often pick up the lessons quite fast and relate these to their own experiences. This is particularly true when they are exposed to what other countries are doing. Well-planned study tours often help change the mindset of government officials. These officials may not immediately apply the lessons they have learned but they usually end up being less cynical about reform ideas than before.

Few bold reformers but many silent change agents While there are few bold reformers, there are indeed many silent reformers. Many government officials have a desire to make good things happen, even if on a modest scale within their small domains. Many small reforms in Bangladesh happened that way. Some big reforms driven from above, got traction when they received support from such small reformers. An important challenge of change management in Bangladesh is to trigger these latent reformers. Catalysts who want change may need to cast the net wide and work at various levels of government, from senior to junior. It is important to work with the senior government functionaries but one should not depend too much on one or two key reformers. The middle levels of bureaucracy are an untapped resource; when incentivised they can do a lot (see appendix). Belief that government knows all answers yet heavily influenced by civil society However, this "know-it-all" attitude is often superficial. Deep down, government officials are influenced considerably by civil society leaders and the media. Comments made by civil society leaders in seminars, op-eds and TV talk-shows are closely followed and help shape opinions in government. Senior government officials are concerned about what the media will write and sustained media coverage about specific issues often lead to action. By the same token, anti-reform comments by civil society leaders also get wide publicity and have impact on government officials.

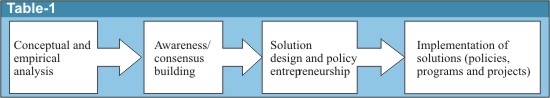

Getting the government going: need for a multi-track

approach Sustained improvements to the investment climate in Bangladesh will require work on four fronts, starting from conceptual work in the universities to the implementation of policies, programs and projects in government. While the focus in Table-1 is on the last front, i.e., actions by government, all four fronts are important and work on each feeds into the next. The role of change agents will vary across the whole chain. However, they have a significant role in all areas. Conceptual and empirical analysis Beyond the conceptual work on these fundamental topics, there is need for solid data collection and sound empirical work. This could include a variety of empirical studies with an operational focus. Some studies may involve collection of primary data (e.g. through surveys of the private sector) while others may rely on secondary data. Some may be long-term in nature while others may provide answers to immediate policy questions. Examples of subjects that could be covered include statistical analysis of productivity, in-depth studies of individual sectors, surveys of investor perceptions and assessments of the investment climate in particular regions. Such studies have an operational focus they identify investment climate constraints, help develop solutions to address these constraints, and identify the potential costs and benefits of these solutions. Few think-tanks in Bangladesh conduct research on investment climate issues, primarily as a result of the lack of resources for such research. This should change given the importance of the subject and more resources need to flow to think-tanks to conduct research on these issues. There is also need for statistical work; indeed, a data bank on critical investment related indicators has become critical. Think-tanks such as the Bangladesh Institute for Development Studies (BIDS) may have a comparative advantage in such analysis and thus lead these efforts. However, one may envision a network model where people in other institutions, such as universities, consulting firms or government agencies, participate in a research program with a think-tank acting as the hub. The links between research and advocacy The universities and think-tanks have this research capacity. But they are not deploying it towards investment climate research. Research emanating from the universities on investment climate issues is sporadic, infrequent and uncoordinated. No mechanism exists to conduct long-term research. There is a need to bridge the schisms between these two groups and develop a rich, indigenous knowledge base that can be leveraged for investment climate research and advocacy in Bangladesh. There are people who do champion business reforms. But usually their interactions with policy makers are sporadic and ad hoc in nature, and often lack concrete information on the problems and what needs to be done. There is need for a coalition of champions who would advocate for business reforms with policymakers in a coordinated and holistic fashion. They need appropriate information, data and statistics. Awareness and consensus building The first is the dialogue track. Institutions such as the CPD, Bangladesh Enterprise Institute and the private sector chambers will have a comparative advantage in this. However, others such as BIDS, Unnayan Shomunnay, Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) and the Brac Institute for Governance Studies (IGS) may also arrange dialogues as they have done in the past. The second is the media track. The media often does not accord business news the importance it deserves and many in the media do not understand business reform issues well. But it does have a powerful role to play in increasing understanding and awareness of investment climate issues; it should advocate and generate support for reforms in this area. Catalysts for change should thus place a premium on working with the media. Journalists need a number of things -- on-the-job training to build business journalism capacity, access to findings of the latest research on investment climate issues, and channels of dialogue with key stakeholders. The media can also do a better job of reporting on reforms actually undertaken. Currently, their reporting on government reforms is rather arbitrary and sporadic. It will be useful if the media regularly collect feedback from various stakeholders on reforms and pass it on to the public sector. Think tanks have a role here. Some think-tanks have high influence and media credibility. But few of them produce and disseminate high quality policy briefs, or hold high quality advocacy events. Think-tanks need to use their media credibility in an effective manner. It is true that some think-tanks are able to attract media attention to their dialogues and other events. But this is still falling short of a concerted effort to brief and educate media so that media reporting is of a high quality. Think-tanks may require some capacity building to develop communications and advocacy skills. Solution design and policy entrepreneurship Once the solutions are designed, they need to be sold to the government unless the government has been involved in the process from the beginning. When governments are pro-active, there is less need for such policy entrepreneurship. One can bank on the government to pro-actively seek out the findings of empirical research and identify where consensus has been reached by various stake-holders. If the dialogues organised by think-tanks do not reach a consensus, the government may itself step in and resolve the trade-off in a way that balances technical appropriateness with political considerations. But often governments do not behave in such a pro-active fashion. This is where some groups in society need to play the role of a policy entrepreneur. This is also advocacy but it is going beyond simply talking about problems and general solutions. The policy entrepreneurs will need to be prepared with specifics, such as suggested drafts of policies or fairly detailed design of specific programs, and then present these to the government for their consideration. Specific proposals help because government functionaries usually show little interest in recommendations that are not clear or specific, rejecting them as infeasible or unworkable. For policy entrepreneurs, patience and doggedness is the name of the game. They need to sustain their efforts and keep at it till something is done. One-shot interactions with government are not enough and it would be naïve to think that governments, even when presented with specific suggestions, will immediately act upon them. A major lacunae in Bangladesh is the paucity of single-issue advocates. A case in point is the Centre for Policy Dialogue. This influential institution has played a useful role in sensitising people on a large number of areas but, apart from trade policy, it has not doggedly lobbied for reforms in any particular economic policy area. Analysis, design and implementation within government The same is true for analytic work done outside government. Government agencies should help develop terms of reference for empirical research so that these are operationally useful. They should also have the capacity to translate the findings of empirical work into policy and project work. Civil society institutions could play a valuable role in helping to build government capacity in all these areas. A good example of this is the work done by the Centre for Policy Dialogue in helping to build trade policy capacity in the Ministry of Commerce. The government also needs to do a better job at publicising reforms which they have carried out. Currently, the line ministries and other government agencies do not disseminate information on reforms and their impact in a systematic manner. This is partly because they are often unaware of the true impact of their own actions. A good monitoring and evaluation system should be part and parcel of any reform program. One of the weaknesses of the last caretaker government, for example, was its failure to communicate to the public, or even the key stakeholders, the reforms they were undertaking to improve the investment climate. An IFC-sponsored survey of various stakeholders carried out in the last quarter of 2008 found that very few people (less than 5%) knew about the Regulatory Reforms Commission and the Bangladesh Better Business Forum, two important institutions created by that government. Yet, when the same respondents were given specifics about the mandates of these two institutions, an overwhelming proportion -- almost 80% -- expressed support.

Catalyzing change: the bottom line Catalysing investment climate reforms is a challenging task. This will require many talents and actions on multiple fronts. There is need for patience and staying power, for creativity and innovation, for networking and coalition building. It will be a challenge. But at the end of the day, it will be worthwhile. Those who decide to become champions of investment climate reform will find this a noble mission. APPENDIX Awakening the sleeping bureaucracy Traditionally, civil service officials of Bangladesh are not proactive about business related reforms. They are used to playing their roles as regulators to control and manage, and are not confident enough to champion themselves as facilitators of private sector development. Most of the civil servants of Bangladesh have only a general understanding of the importance of creating a climate conducive to private sector led growth. They lack the knowledge and skills required to identify and initiate reforms for private sector led growth and usually do not get opportunities to learn from the successful initiatives of other countries. They lack the incentives to learn by themselves and to utilise their knowledge in their jobs. The overwhelming mistrust between the public and private sectors also discourages them from being proactive. Nonetheless, there does exist a latent desire among many civil servants to learn and do something good - even if it is within their limited jurisdictions. A critical mass of latent reforms still exists in the present bureaucratic system and they have the potential to become agents of change. They also have the willingness to champion themselves as proactive reformers. The challenge is to trigger this latent desire. With the support of the International Finance Corporation and a local think-tank, the Bangladesh Enterprise Institute, the government last year formed a group of mid-level government officials who went through a eight month program of sensitisation to investment climate issues. The program, which was launched in June 2008 and ended in March 2009 had 48 participants, including 38 participants from 30 government ministries and agencies, and 10 from private sector business associations. The program consisted of lectures, seminars and workshops on various investment climate related subjects, study tours within the country and abroad, and specialised courses on English language and basic computer skills. The officials were mostly mid-level, i.e., at the Deputy Secretary level. Why mid-level civil servants? Because, they are key players in the Bangladesh bureaucracy, responsible for implementation of projects and policies and also playing an important role in initiating the formulation of policies and regulations. They can make or break things. However, despite their importance, they are often overlooked. The inclusion of private sector representatives generated cross-fertilisation and created unique opportunities for government officials and private sector representatives to work together on investment climate issues of Bangladesh. The government officials also found this to be a great opportunity to know their own colleagues in government and become familiar with the work of their ministries and agencies. For example, several participants commented that they had heard, but knew little, about export processing zones (EPZs) till their fellow core group members from the EPZ authority arranged a visit to one of the EPZs. The contacts forged through the program have been maintained in most cases. Several officials who have gone through the program are now showing pro-activeness in identifying and advocating reform issues. For example, about 10 articles and op-eds have been written by the officials on reform issues in leading national dailies. This is rather unusual for civil servants who traditionally do not write in the public media; yet, the quality of the writing suggests that these officials have very good writing abilities which have just not been nurtured so far. Several of them have identified reform actions within their own ministries and agencies. Each of them may be small in nature but cumulatively they are big. Even bigger is the awakening of the sleeping reformers and the change in their mind sets. Syed Akhter Mahmud is with the International Finance Corporation |