Inside

|

Just Another Bomb Blast in Afghanistan SYED A. MAHMOOD recalls heroism at a perilious time

Sometimes, we would catch a glimpse of the smiling face and the light hand-wave of the dignitary. Often, even that would elude us. We would wonder what the point of all this was, whether the VIP had any idea of the torture we had gone through so that his or her spirits could be uplifted by the sight of smiling and waving school kids. We wondered if they knew that the smiles were more of relief than excitement. But, never, in our worst nightmares, did we worry that we could lose our lives; that the merciless action of someone could put shrapnel through our bodies; that we could be killed or forever maimed. Yet, on an otherwise beautiful day in the peaceful town of Baghlan, this is exactly what happened to dozens of Afghan schoolchildren. Once the capital of Qataghan, a province that was dissolved in 1964, Baghlan is now home to about 120,000 people. They are mostly Pashtus and Tajiks along with a smattering of Uzbeks. A short but helpful entry in Wikipedia tells us that Baghlan was once a sleepy village in the lap of the Hindukush, 1,700 metres above sea level and three miles east of the Kunduz River. Baghlan's isolation diminished after the 1930s, when a new road built across the Kunduz linked it to Kabul, gradually turning the village into a small but important urban centre. Baghlan is now the centre of sugar beet production in Afghanistan, although cotton production and manufacturing are also important activities. That November day, it was indeed a sugar factory that a group of politicians had come to visit. The group included several members of the Afghan parliament, including six members of its economic sub-committee, and many town people had gathered to welcome them.

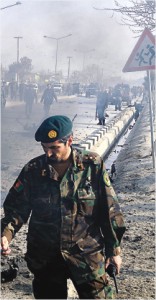

Waiting in front of the sugar factory were local politicians, government officials, newspaper reporters, and factory workers. There were dozens of school children too in their best dresses, waiting to sing the songs they had rehearsed for many days. One man in the crowd had a bag full of ball bearings. No one noticed, no one cared; it could have been a small trader going about his business and just pausing to check what was going on. Only one man standing at a safe distance knew something the others did not -- that there was more in the bag than just ball bearings. A few minutes later, as the visiting dignitaries made their way through the crowding, a huge blast shattered the joyous environment. As anguished cries went off, and people stood numbed, dazed and confused, the man in the distance hurriedly left. His job was done. I first read about this in the on-line edition of the New York Times. The early report did not have a full count of the casualties. The headline, which vastly under-reported the number of dead, said simply: "26 dead in Afghan suicide blast." The first paragraph was a repeat of news items about Afghanistan that I had become so familiar with: "A suicide attacker threw himself at a delegation of lawmakers visiting a town in northern Afghanistan on Tuesday, killing as many as 26 people, including a leading opposition figure, and wounding scores more, local and regional Afghan officials said." Sad though it may seem, I had become used to such dispatches from Afghanistan. It was just another bomb blast in Afghanistan, I thought, and was about to move on to other stories.

The next paragraph, consisting of a single sentence, drew my attention: "Many of the victims were schoolchildren performing at a welcoming ceremony." I started having the same thought that has haunted me ever since I came to know this beautiful but unfortunate country: when will this all stop? And where were the leaders who could ensure that Afghans are forever spared such tragedies? Karzai was clearly failing and the old warlords could not be trusted. My thoughts then drifted towards Sayed Mustafa Kazemi. A strikingly handsome man, even by Afghan standards, Mustafa Kazemi was Afghanistan's commerce minister when I first met him in early 2004. I had walked into his room with the usual trepidation you have when meeting a minister. The interlocutor, either a fellow World Bank staff or an official of the Commerce Ministry -- I do not remember exactly now -- introduced me as Syed Mahmood (the name that I was known by at my work place in deference to the western practice of using one's first name). Suddenly, Mr. Kazemi's eyes opened up, his smile became broader, and as his hands clasped mine in one of the warmest handshakes I have ever experienced, he repeated my name, with an extra emphasis on the word "Syed." I noted he was a Syed too, and that emphasis reminded me of something I had heard many years ago -- that Afghans have a special regard for "Syeds," believed to be people with a direct lineage to the Prophet.

And it was not reassuring that within two hours of landing in Kabul, I had to go, with many other officials of international organisations making their first trip to Afghanistan, to a UN briefing session, where we learned not about the culture and literature of Afghanistan but about the different sizes and shapes of car bombs. But Kabul was a warm place. The snow-capped mountains in the distance, the bright sunshine, the crowded streets and, above all, the friendliness of the people, kept telling me that it can't be all that bad. But the meeting with Mr. Kazemi was the tipping point -- his warm hand-shake and the emphasised mention of my first name made me feel immediately at home. The subsequent discussions got me excited about Afghanistan's future. Minister Kazemi knew English but was not fluent (which he admitted with a nice, shy, smile) and chose to speak through an interpreter. That was good, because by then I had come to love the sound of the Pushto-Dari language, its cadences and intonations, its emphases and lovely phrases. And Sayed Kazemi spoke with a lot of passion, with a constant twinkle in his eyes, and breaking out in broad smiles every now and then. He was best when he spoke of the sad history of his country, of how things once were, of the dreams they once had of returning to the peace and serenity they knew as children. Like many Afghans of his age, Sayed Kazemi had been unable to finish a college education because of the war, and he was determined that this would not be the fate of his children. The pathos made the man even more handsome; his face and expressions showing simultaneously the pain and hopes, and the fear and dreams, of the people of this tragic but beautiful land. I had only thirty minutes with him. But as he started speaking of his dreams, Kazemi forgot his other appointments -- the thirty minute appointment turned into an hour long conversation. That day, in the hour that I had with him, the minister laid out his dreams and plans for reviving Afghanistan's economy. He was particularly keen to revive an industry that Afghanistan had once been famous for, dried fruits and nuts -- pomegranates and peaches, apples and apricots.

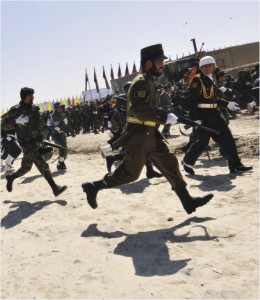

He told us of orchards and farms, of soil types and climates, of small factories tucked away in lovely valleys that processed the fruits and nuts and packed them for export to distant lands. And he told us about the distant lands, about Europe and America, about Indonesia and Africa, and about the not so distant lands of India and the Middle East, where breakfast started with juices, and dinner ended with almonds and apricots from the mountains and valleys of the enchanted land of Afghanistan. One could not help but be inspired by him. In September 2005, after the first parliamentary elections, Sayed Mustafa Kazemi had to give up his cabinet seat. In an effort to reduce the influence of the warlords and keep them out of his cabinet, Karzai had engineered a rule that prohibited people without a university degree to be in the cabinet. Kazemi, who was far from a warlord, was part of the collateral damage. Unable to complete his university education due to the war, Kazemi was left out. But he was elected to the parliament and soon became a powerful voice for integrity, reason, and progress. As head of the United National Front, he was one of a younger generation of leaders eager to pull Afghanistan out of the destructions of war. On the day of the bombng, I started thinking of Kazemi. While the sad event, especially the death of so many innocent school children left me profoundly depressed, I found hope in Kazemi and the dozens of leaders like him who inspired faith in a bright Afghan future. I hoped one day he would be back in cabinet, perhaps even become president of his beleaguered land, and with the help of many others like him, revive the country, the orchards and the farms, the factories and the universities, and inspire Afghans to dream big again. In the despair of that tragic bomb attack, I could still afford to be optimistic. But tragedy has no bounds in Afghanistan, a land where hopes are raised only to be dashed again. As I continued to read the New York Times article, a shiver ran up my spine. The group of Afghan parliamentarians that was visiting Baghlan that day was led by no other than Syed Mustafa Kazemi. He had gone to see the re-opening of the sugar factory, once an important part of Baghlan's economy, but had been closed for several decades. For a man who dreamed of reviving Afghanistan's factories, and who one day had ignored all his important appointments so that he could tell a fellow Syed from Bangladesh about his dreams, this must have been a great moment. But tragedy struck and like many other Afghan dreams, this too was shattered. Kazemi was a man of the future but others harkened back to the past. That day, the latter had the upper hand. In the peaceful town of Baghlan, in the lap of the Hindukush, three miles east of the Kunduz River, Kazemi's blood mingled with that of 59 schoolchildren for whom he was dreaming a new future. Syed Mustafa Kazemi was only 45 the day he was struck down by the Baghlan bomber. Syed Akhter Mahmud is with the International Finance Corporation.

|

W

W

That was my first visit to Afghanistan and the meeting took place on the third day of my visit. I was still unsure of things in this troubled and risky land. My wife had not wanted me to work in Afghanistan, having had her own worries about security compounded by the reactions of whoever she had mentioned my impending visit to: "What, Afghanistan?!" or "Does he really have to go there?!"

That was my first visit to Afghanistan and the meeting took place on the third day of my visit. I was still unsure of things in this troubled and risky land. My wife had not wanted me to work in Afghanistan, having had her own worries about security compounded by the reactions of whoever she had mentioned my impending visit to: "What, Afghanistan?!" or "Does he really have to go there?!"