Inside

|

Reaping the Whirlwind ZIAUDDIN CHOUDHURY traces the roots of radicalism in Bangladesh

ALMOST every week these days we find in the news reports of arrests made by police of elements that are associated with religious militancy. Some of them have been in the wanted list for having direct connections to acts of assassination or other destruction, some for suspicion of connection with militant organizations and bodies. This should not surprise us as for long we had nurtured these elements, even coddled them for short-term political gains. I say short-term with some hesitation, as I am not fully convinced that among some of the political patrons of there are elements who do not indulge long-term goals of establishing an alternative system of governance in the country. Nevertheless, we should be thankful that there is now a genuine effort in containing the radical forces that were set loose in an earlier period. What should concern us, however, is the presence of a mindset among our political leaders that could be opposed to building a society that is free from religious bigotry, intolerance of religious and political differences, and violent imposition of religious doctrines. History is witness that profession of this school of thought had led to acrimonious debates within the community, and ultimately to civil wars. Within a few years of our hard fought independence we saw a premature demise of the ideals of secularism, and dream of a pluralistic society built on the beliefs and cultures of multiple faiths. We witnessed contemptible attempts to denigrate our nationhood based on our language and culture, in favor of religious identity alone that was mightily unsuccessful in keeping us wedded to a geographically dispersed entity before. Unfortunately, these malignant forces, contrary to the values for which we fought, did not take birth in a vacuum. They have been always present with both internal and external help.

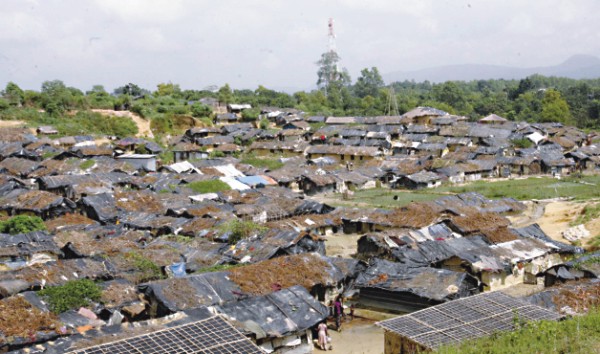

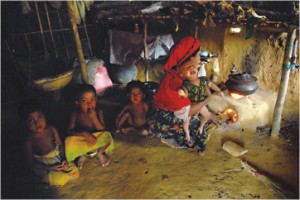

Internally, these forces have been sustained by elements that had always aligned themselves to a political ideology based on religion alone. These elements were dormant in the initial years of our independence, but were stoked back into life after the founder of our nation was cruelly struck down. People who date back to the early seventies will remember that among the first to embrace General Ziaur Rahman as the saviour of the country were the leaders of the Madrassa Board and other religious organisations that were practically defunct immediately after the independence. Externally, the forces have been aided and abetted by the proselytisers of a political philosophy that seeks a forced imposition of religious dogma on our life and politics. A principal way to propagate this ideology has been through financing of institutions for religious education, and religious charities. The prime example being the exponential growth in private madrassas in the country in last two decades, and the upsurge in religious charities (NGOs) that have little audit of the sources of their funds. In the case of Bangladesh, however, one of the ways the seeds of external encroachment to guide and assist the radical forces were sown from across our eastern border. I believe the foot in the door for the global network to proselytise the radical version of religion was made possible in our country by the first influx of the Rohingya Muslims from Arakan in Burma (now Myanmar) to Bangladesh in 1978. As deputy commissioner of Chittagong during that period, I was on the receiving end of the influx and had toiled over months with my colleagues to provide food and shelter to hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children. In the first week of this exodus about ten to twenty thousand refugees arrived all of whom were accommodated with local help in schools, cyclone shelters, and make shift tents. However, as time passed and more and more shelters were established along the Burma border after international agencies got in to help, the number of refugees sweltered to around two hundred thousand. Our initial thinking, when the first wave of refugees arrived at the borders in tattered clothes, was that they were victims of a brutal ethnic cleansing effort launched by a junta. The refugees claimed that they were driven out of their villages by marauding Burmese army intent upon killing all "Muslims." I had no idea until that time Arakan had a substantial Muslim population. However, the stories given out by the refugees were not consistent. While a good number stated that they were hounded by the army for their religion, others stated it was because of their ethnicity. The only consistent story was that that they had left behind their hearth and homes out of some fear. The ethnicity part appeared more credible to me as the refugees were of Bengali origin, a large number of who had actually migrated to Burma only a generation before. Moreover, the claims by the Burmese authority that period were that these refugees were mostly illegal, and the effort of the government was only directed against the illegal citizens only. In the midst of these conflicting stories about the reasons for the mass exodus of the Arakan Muslims I received some astounding information from a traveling journalist of the Far Eastern Economic Review (now defunct) on these events. The journalist, a British reporter, was visiting the area like many other international journalists who came to witness and report on the mass migration. While interviewing me, the journalist stated that the he had visited the Burmese side before coming to Chittagong where he had interviewed the main leaders of the Rohingya "guerillas." I was struck to no end by hearing the word "guerillas" as I had assumed like many others, both within and outside our country, that the refugees were hapless victims of a brutal ethnic cleansing. I was to further learn first time about Rohingya Land for Muslims in the Arakan state that the guerillas stood for. He further informed me that although many refugees had fled Arakan to escape the immigration check by the Burmese authorities (called Operation Nagamin), a large number had been persuaded to leave by the Rohingya Liberation Front (aka Rohingya Solidarity Organisation), the main guerilla organisation that time. I found the information so alarming, but useful at the same time, that I alerted our government to this additional dimension to our mounting refugee problem. The new information notwithstanding, we could not stop the wave of refugees crossing daily our eastern border, and we could not help but continue to shelter them. Our law enforcement authorities had no way to verify who among these refugees were actual guerillas as none carried any weapons, at least openly. The involvement of UNHCR and other international aid agencies also made it difficult for us to discriminate based on suspicions of affiliation of any of the refugees with any armed guerilla group. Our government's intention that time was not escalate the problem to international level, but to repatriate the refugees negotiating with Burma, in which we succeeded. With the number of refugees growing every day, the government allowed more and more foreign organisations to come forward with assistance, including Rabita al-Alam al-Islami, a religious charity based in Saudi Arabia. The nexus of the Rohingya guerillas with our own radical elements first came to my attention when the sub-divisional officer of Cox's Bazar stated that he had received an application for lease of government land in Ukhiya (a thana bordering Burma where the majority of the refugees were camped). The lease requested was for establishment of a mosque and hospital with financing from Rabita al Alam al Islami. Since the charity organisation was foreign, the application for lease was made by a local resident. Normally this would not pose a problem since the sponsor was a known international charity organisation. But the problem was the applicant who, according our records, had been an active member of the student wing of Jamat-e-Islami, which that time was a banned organisation. The applicant was prosecuted under the Collaborator Ordinance, but unfortunately the case was dropped along with others when the general amnesty was proclaimed by Bangabandhu. Nonetheless, I had no hesitation to ask the SDO to reject the application, knowing about the applicant's identity. I knew also well that there would be consequences to this decision. There were consequences. The applicant had friends in higher places, particularly in the Ministry of Home Affairs that period, who asked the SDO the reasons for denial. The ball finally rolled to my court, and I had to defend our decision citing serious local opposition to the applicant who was still remembered in the area for his criminal role during the war of liberation. I believe the matter went up to President Zia who, for reasons best known to him, did not want to pursue the case of the collaborator, at least while he was alive. I say while he was alive because shortly after the takeover of the government by General Ershad, permission was given to the same person and his allies to establish the hospital and religious centre in Ukhiya under Rabita banner. A centre was established right across our border that would provide relief and support to a militant organisation that was fighting an ongoing battle with its own government. Unfortunately, it would take us more than a decade to realise to our peril that in the wake of showing our hospitality to the Rohingya refugees we had also invited a group of militants who would be allies to radical extremists in our country. Reportedly, the Rohingya movement not only fed arms to our militants but provided a fertile ground for recruitment of religious militants world-wide as far as Afghanistan and Bosnia. If last several years experiences are any lesson, we should do well to follow the trails of destruction and hound out all elements, past, present, and future to weed out the threat of militancy that our country had been exposed to. There have been some laudable actions in the last two years. The most salient features of these have been arrest, prosecution, and meting out of exemplary punishment to some of these radical elements. But the looming fear is that with the continued mind-set in some of our political leaders to gain support from these elements for political power we may fall back to these hands and expose our society, and country at large to possible anarchy. My fear is because we have yet to identify and unearth the real forces that were behind the arms smuggling of Chittagong because of the unseen political hands that prop up the radical elements. My fear of the resurgence of the radical forces grows when I still see that some of our political leaders are out to muddy the prosecution of the war criminals on pretext of political opposition to the party in power. All I can hope is that our leaders rise above their narrow goal of short-term political alliance with a force that we all know does not believe in a pluralistic society or liberal democracy, ideals that we want our nation to be built upon. Ziauddin Choudhury is a former civil servant in Bangladesh who now works for an international organisation. |