Inside

|

A Tale of Two Cities S. AMINUL ISLAM questions urban planning in Dhaka and provides his vision for the future

DHAKA, from a small population of 90,000 in the 1700s, is projected, according to the population division of the United Nations, to have 22 million people by 2025, and turn into the fourth largest city in the world. Since independence, Dhaka has become a city of crowds, chaos, and immobility. One single statistic by the Economist Intelligence Unit encapsulates the story of Dhaka. It is ranked the second least livable city in the world. It has become for Dhakaites, to borrow an epitaph of Bertold Brecht for New York, a real "inferno." Robert Ezra Park, the leading figure at the Chicago School of Urban Sociology, underscored clock as the symbol of city, and city as the epitome of modernity. The city, although haunted by the spectre of disorganisation, represented speed of movement, regularity and rule -- a built structure of impeccable order -- an orchestrated social life from birth to death. Several decades after "one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five," when Dickens' story begins, Paris was a miserable city. Even in the 1820s, an approaching visitor could identify the city from a long distance simply from the smell of its open sewers. But from the 1850s, Paris, perhaps more than any other city in the world, gave birth to different paradigms of urban planning and architecture that might be instructive in envisioning the future of Dhaka.

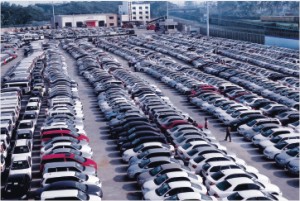

In 1853, Napoleon III, writes Jeffrey Schwartz, envisioned for Paris "a city of marble" to rival Rome, and through his new prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugene Haussmann, undertook to rebuild the city through a grand and unified vision for movement of people and goods necessary for an ascendant bourgeoisie. Haussmann, an engineer by profession, viewed his task as "functionally providing for Paris's nourishment through the circulation of the roads that were its arteries, the parks that were its lungs and the sewers that provided for the disposal of its waste." The project involved rebuilding one-fifth of its streets. Haussmann had spent 2.5 billion francs through a new mechanism at the time -- debt-financing. With its more than three thousand gaslights -- a novelty of the time -- Paris had turned into a wonder of the world, a luminous spectacle with its streets, boulevards, parks, and gardens. Paris thus dramatically offers the architectural vision and urban planning paradigm of early modernism. Over three-quarters of a century later, Paris had become clogged with traffic and crowded with people. It partly inspired a young architect in the 1920s to develop a new and revolutionary vision of urban planning. Coming from the family of watch-makers in Switzerland, Le Corbusier (Charles Édouard Jeanneret Gris, 1887-1965) set for himself the task of establishing a clocklike order in the urban space with the slogan: Architecture or Revolution. The central problem for him was how to solve the constraints of space for a hugely growing population. He solved the problem in a fundamentally new way. The 19th century city was a city of streets and he transformed the city of streets into the city of highways -- into "a factory for producing traffic." He gave birth to a totally new vision of urban space -- a city with super highways, high-rise buildings, and underground garages that solved the problem of urban space for the time being. Thus was born the paradigm of what can be called high modernism. Although his grand vision for Paris was ignored, his influence endured and spread all over the world from Chandigarh to Brasilia. In the early 1960s, the problems of Paris became very acute due to high migration from rural areas. De Gaulle wanted to bring "a little order in Paris." He is known to have taken Paul Delouvrier up in a helicopter, and ordered him to clean up the "crumbling suburbs" and their narrow streets. Delouvrier, as the prefect of Paris region, embarked upon what Peter Hall calls the most "grandiose" plan ever "attempted in the history of urban civilisation." The hallmark of the plan was the construction of satellite cities connected by express transit system. Thus Paris ultimately had five new towns planned for 300,000 to 1,000,000, three huge motorways and five rapid express railway lines. Meanwhile the vision of Le Corbusier -- the vision of high modernist architecture --collapsed precisely at 3:32 pm on July 15, 1972 when dynamite was charged inside the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Projects in St Louis, US -- an icon of all that went wrong with the modernist paradigm -- and many herald it as the symbolic moment when the paradigm of post-modernism was born. Post-modern architecture and urban planning celebrates the heterogeneity, eclecticism, pluralism, and the paradox manifested in the AT&T Building of New York or the city of Los Angeles. The failure of modernism was also evident in Paris. Even Paul Delouvrier's grand plan failed to solve the problems of Paris. From the 1970s the north-eastern parts of the city began to suffer de-industrialisation, and parts of it became deserts of unemployment, which turned into ghettos leading to two cities of Paris -- the south-west and north-east -- that gave rise to greater social tension. The riots of 2005 were an outburst of this simmering tension. It is in this context French President Nicolas Sarkozy in 2008 unfolded his vision for "grand Paris" -- for turning it into the finest example of post-Kyoto city -- inclusive and eco-friendly. He moved ahead with his grand vision by creating the office of secretary of state for the capital region and entrusting Christian Blanc for implementing this vision. The story of Paris has several lessons for the future of Dhaka. Firstly, there is no simple or final solution for giant cities. No single paradigm is sufficient for dealing with the complex dynamics of urban growth. Secondly, the building of a great city demands the highest commitment and grandest of visions. Thirdly, it requires financial innovations. Finally, the greatest challenge for Dhaka is to redesign the social architecture of urban life-attitudes and behaviour of urbanites, for the city is perpetually threatened by what Le Bon feared as the reign of crowds, something which Robert Park termed "urban disorganisation." There is no dearth of plans and strategies for Dhaka. Debates have raged over the best strategy for movement of people and vehicles -- arguments for and against fly-overs, as if there is a single or ultimate solution for everything. There has been strong opposition to building expressways/fly-overs in Dhaka. Although it is true that no expressway has been built in Europe in the last two decades, most third world countries are going ahead with building them. The reason is not difficult to understand: Western cities are growing slowly and even losing population, thus there simply is no need to construct new expressways. With a large build up of private cars, Dhaka needs expressways/fly-overs. One advantage of fly-overs is that they can now be built quickly. Some fly-overs in Chennai and Delhi have been built using latest technologies within less than two years. A Japanese firm called Daiho claims to have developed a new technique to build fly-overs at busy intersections of the city, something that can be constructed within four months and can significantly improve traffic flow. But fly-overs alone are not going to solve Dhaka's problems. What we need for Dhaka are integrated policies spanning a time-horizon for implementation, and including macro and micro interventions that can serve the needs of different socio-economic groups and areas of the city. Given the socio-economic conditions of the country, a bus rapid transit system (BRT) has to be the hinge of the transportation of the city in the short run. Sao Paulo has the largest BRT system in the world with 12,000 buses that carry 4.8 million passengers per day. We will perhaps have to wait for a metro for a decade or two: we simply don't have the financial, technical capabilities, or infrastructure for it. We must be particularly careful before we venture into building underground metro for Dhaka largely sits on a substratum of young or soft soil-inceptisol. It is again both difficult and expensive to design a structure that will be able to withstand once-in-a-century catastrophic flood in a climate regime of escalating extreme disasters. We also need to build up an eco-friendly city, for example, and keep the existing rickshaws. In the old part of the city of Delhi (where the only transport is rickshaw), rickshaws are being run experimentally by solar power. Rickshaws are eco-friendly and provide income for the poor and so there is every reason to promote rickshaws in Dhaka. There is again need for relocating some factories, schools, and offices. Perhaps a new city can be built on the other side of the Buriganga. The older part of the city can be preserved like the old city of Beijing and the waterfront developed in a fabulous way. Urban planners in developed countries are now using new techniques and computer software for imaging, planning and managing cities. Given these new facilities, it will not be difficult to achieve an effective traffic control in the city. But perhaps what is more challenging is to transform human behaviour in the city. Dhaka is characterised by a strong rural pull. The emerging urban culture is highly fragmented in terms of Kutti, indigenous Bengali, Islamic revivalist, Western and hybrid "sub-cultures." It is also characterised by widespread anomie or absence of norms and rules -- which absence is best manifested in the chaos on the streets of Dhaka. As a young man, Le Corbusier held firmly that Paris could be saved by a great vision. This is also true for Dhaka. Brasilia, the new capital of Brazil, was built in four years. Dhaka can be transformed completely during the tenure of the present government. It will require a strong and innovative leadership and deep public participation. It will require an effective partnership among the prime minister, a state minister who will be solely in charge of rebuilding Dhaka, and a newly elected mayor of Dhaka, and financial innovations. We are still celebrating the four hundred years of the city. It is the most fitting moment to broaden the government's initiatives in a fundamentally new way so that the future historians of Dhaka can call it, to borrow the phrase from Dickens, "the worst of times" and "the best of times." S. Aminul Islam is Professor of Sociology, University of Dhaka. |