Inside

|

The Transfer Chronicles QUAZI ZULQUARNAIN ISLAM explains the art of winning an unfair game

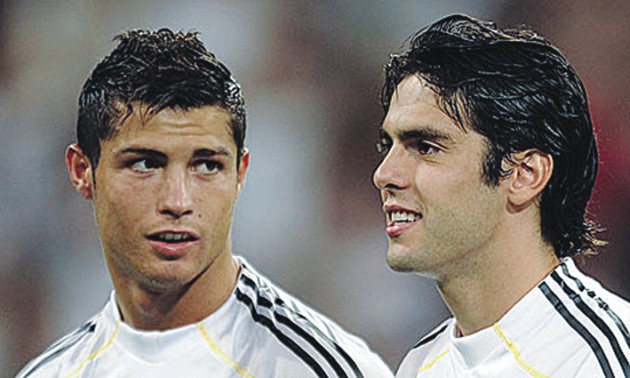

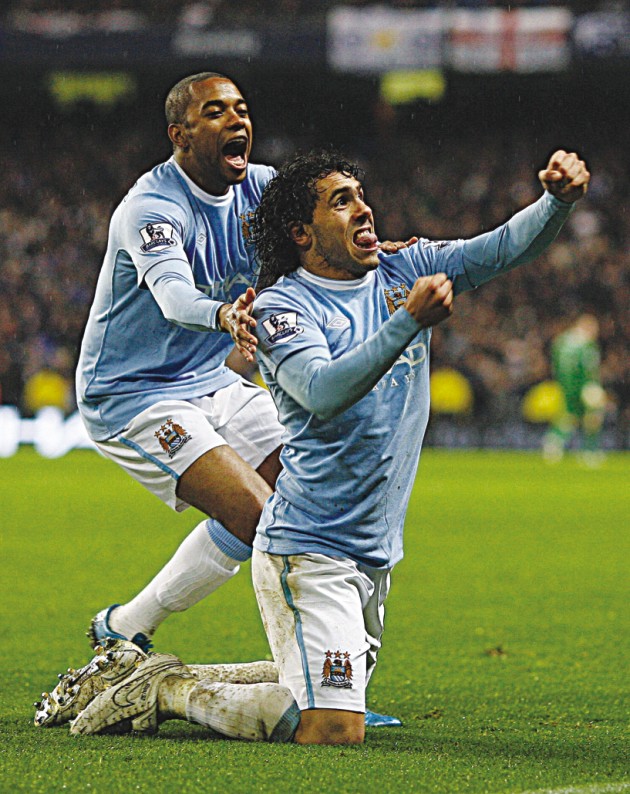

For every hard-core football fan, of which there are many in Bangladesh, the summer months can be long and arduous. League season in Europe winds down with the Champions League final in May and unless you are an aficionado of the Icelandic or Russian leagues, June-August will most likely be spent in a state of hope/despair, depending on the performance of your chosen team in the corresponding season. Of course, every two years, you have either the European Championship or the World Cup to keep you busy, but often even these heady tournaments take a back-seat to the single most important activity for the summer transfers. Transfers are a unique activity and it would not be wrong to say that they are almost football's lifeblood. People talk about them, the press jump on them and the clubs see it as a way of improving their playing staff while at the same time appeasing their demanding fans. The blood-thirsty nature of transfers mean, that every off-season (and for a short while in January) fans are baying for new blood. Newspapers are abound with rumours of fresh recruitments by big clubs and all this means that the clubs are always under undue pressure to sign up the next big star name to their books. The short time span, lack of proper planning, and high competition mean that more often than not a lot of transfers turn into busts. Take the case of AC Milan for example. In the early 1980's, a Milan scout spotted a feisty young black forward playing for English upstarts Watford. Rumour has it, that the player was John Barnes. But the poor scout, suffered from a case of mistaken identity and instead roped in the hapless Luther Blissett for the princely sum of 1 million pounds. Suffice to say, Blissett's time at the San Siro was acrimonious, and his name is now synonymous with anarchy, in the fashion capital of Milan. But those were the halcyon days of the 80's. As football gained more professionalism and as scouts were increasingly fed with information gleaned from every corner of the globe, you would expect transfer activity to have been perfected to an almost exact science. Right? Wrong. The truth is, clubs continue to rope in players with hardly any thought to proper planning. Small wonder then, that a high percentage of transfers end up being expensive failures. For a more recent example, one only has to look at the supposedly infallible Sir Alex Ferguson. After the World Cup in 2002, much was made of the decision of the Scot to rope in Brazilian midfielder Kleberson. The previously unheard of midfielder had, according to Ferguson, won Brazil the World Cup. Many were shocked, since Kleberson had played in only a few games in the finals. But Ferguson was convinced, and Kleberson it was, who strutted his stuff in the Theatre of Dreams for two seasons; with understandably tragic results. For an even more recent example, one only has to look at the case of the Portuguese starlet Bebe, signed this season by United. A former homeless World Cup player, Bebe was secured by Ferguson for the princely sum of 7.5 million pounds. So far, he has even failed to crack the reserve team, with his control and touch apparently not good enough. Ferguson admitted, he had never seen Bebe play and this is astonishing for someone who splashed that kind of cash on a player. Yet, Ferguson is not the only example. Clubs often splash out on unknown talent and are left with egg on their faces. Yet, paradoxically, it is this inefficiency (and in some cases wanton disregard) that makes the transfer market and the buying and selling of players so interesting. It's important to remember that in football, there are two crucial "markets" "the wage market" and "the transfer market." Wages are generally considered to be an efficient marker of a player's ability, i.e, the better a player the better he will be paid. A recent study conducted on the league position of English clubs (in the Premier League and the Championship) through the 1998-2007 period showed that spending on salaries by clubs explained their league position to a variation of 89%. Stripped of statistical jargon, what this means is that the higher you pay your players, the higher you generally finish. In the period sampled, Manchester United, Chelsea and Arsenal were the top three clubs in terms of salaries paid. Compare that to their average league positions over the same period and it doesn't take a genius to understand the link. Hence, we can come to the general conclusion, that the market for wages is quite efficient. Thus, if you are paying Cristiano Ronaldo, Frank Lampard and Cesc Fabregas big bucks, you can be certain you won't finish far from top spot. The market for transfers though, is an entirely different story. Take the case of the second most expensive player in history; Kaka. The Brazilian's first season at the Santiago Bernabeu has been insipid by his own lofty standards. And now, with a new coach at the helm it seems that his opportunities may well be very limited and that he may even be forced out of the club. It seems like a classic case of overpaying for a player past his peak. And Kaka is just one glitzy example of an overall inefficient transfer market. The truth is that often clubs buy just the wrong players. Many often raid the South American and African leagues to find the next uncut diamond. Players are bought at an increasingly young age and often never mature. Prima donnas often never settle into the club they were bought in to. But herein is the paradox. Since the transfer market is inefficient, it automatically means that some clubs are underperforming while others are over-performing. In most cases, clubs that fall into the latter category are smaller clubs than your Real Madrids or your Manchester Uniteds. And for the sake of competition it is vital that these small clubs over-perform, because otherwise, they would never be able to compete against the giants of the game. But, why not? Because the truth is that at the end of it all, football is actually an unfair game. The bigger clubs have massive budgets and mega wage structures. Their stadiums are generally bigger and their fan bases are also larger and more global. Yet, they are all competing in a single league with other smaller counterparts, and all for one single prize. For big clubs, it is the equivalent of playing Monopoly with Fleet Street and Mayfair already in the bag; there are only very few ways in which a small club can compete with that. And one of those ways is by mastering an inefficient transfer market.

It is not really rocket science, and a lot of small clubs have already jumped on this and become masters at manipulating the market to secure the best deals. These small clubs cannot afford to pay their players to success, so they choose the route of transfers. The best example is serial French champions Olympique Lyon, but more on that later. First, let us run through some of the more obvious inefficiencies in the transfer market, that these clubs have been able to spot. Honestly, it really does not take someone like Lyon general manger Jean-Michel Aulas or Arsene Wenger to figure these kinks out, but they still exist, mostly due to the conventional belief held by clubs to stick to the tried and trusted ways of doing things. In short, traditionalists are held in high stead and reformists frowned upon in the general structure of club football. More importantly, though, what are these obvious inefficiencies? The first is that tournament (World Cup or European Championship) stars are almost always overvalued. It is fitting to start with this since the World Cup has just concluded. And the first name that would jump off the block is Mesut Oezil. Now, Oezil is a supremely talented player and has been one for quite a few seasons now. But the fact of the matter is that with a single year of his contract remaining, Werder Bremen (more on them later) would have been lucky to get into the two-digit millions for him. As it happened though, Oezil cost Real Madrid as estimated 16 million pounds, with the figure expected to rise into the early 20 million range. Now at the end of it all, Oezil might turn into a huge success, and people will not be complaining. After all, Real have enough cash to burn. But the fact remains that Oezil's value peaked and only peaked so much since he was a star of the World Cup. Another classic example is that of El Hadji Diouf. The Senegal star rose to prominence on the back of a stellar World Cup in 2002, when they famously beat France. This forced through a dream move to Liverpool and Diouf was expected to light up the Premiership. Eight years later, he remains a decent, yet journeyman striker, with dreams of dominance long over. The fact is that as a mark of a player's ability, the World Cup is a frighteningly short sample size to draw from. Seven games if you make it to the final and many players can look very good in seven games. But ask them to maintain that consistency over a league season for a number of seasons and many will fail the test. Secondly, centre-forwards or attacking players in general are almost always overvalued. This is surprising because any manager worth his salt will tell you that strong defences are what usually win you championships. There is a famous mantra, "offence wins games, defence wins championships" and often you will see that the team who wins the league has the best defensive record. In spite of this, forwards or attacking players are always overvalued. Nemanja Vidic was arguably as important as Cristiano Ronaldo to Manchester United's Champions League win in 2008, but put them side by side on transfer value and Vidic will cost only a fraction of what Ronaldo would. In the infamous, Galactico era, Real Madrid had players of the like of Zinedine Zidane and Ronaldo adorn the same pitch. But the brilliance of Iker Casillas is what often kept them in games. Yet, in terms of transfer value a goal-keeper is valued far lower than a forward, despite having more longevity and playing in a more demanding position. Thirdly, certain players, Brazilian or Dutch for example, are in vogue in the transfer market and are considered, for want of a better term, brands. Both the nationalities are traditionally associated with attractive football and clubs end up dishing out far more on them, than their talent deserves. Take the case of the Dutchman Giovani van Bronckhorst or the Brazilian Sylvinho. Both players were considered failures at Arsenal after joining from smaller clubs. Yet their next big moves, ended up being to Barcelona, arguably a bigger and better club than the Gunners! Brazilians evoke a sense of mystique. Clubs reckon that having a Brazilian in the team is fancier than say a Belarussian of equal talent, only because of the positive connotations attached with having the former in the squad. Or how else do you explain, Real Madrid being reluctant to buy the brilliant Serbian Aleksandr Kolarov for a trifle more than they used to buy the error-prone Brazilian Marcelo?

Finally, new managers often always waste a lot of money buying up players who understand his system or he is familiar with. This is almost always easily avoidable, and to be honest, a manager is often a very poor judge of a club's long-term needs. Managers come and go, but clubs remain. Hence, many managers have roped in expensive stars only to be fired few months later. The new man, then again, wants his own players and all this means that there is often a question of expensive turnover, which is hardly beneficial for the club. These are some of the most common asymmetries that are prevalent in the market and this is what makes it possible for some smaller clubs to succeed. As aforementioned, the likes of Lyon and Werder Bremen are the perfect examples of how clubs have identified these inefficiencies and manipulated the transfer market to carve out an existence in a highly competitive game. Lyon first, since their success is one that every small club should look to model. Even a decade ago, Lyon was a small club in a fashionable city where football was not the rage. Their neighbours St Etienne were once the biggest clubs in the land and Lyon was never more than a satellite to their planet. However, in less than ten years Lyon have emerged as the biggest force in France and won seven consecutive titles. How? Much of the credit should rest with Jean-Michel Aulas. Aulas, who took the club over in 1987 has a simple theme; over time the more money a club makes, the more matches it will win, and the more matches it wins, the more money it will make. Aulas has almost perfectly abstracted the time factor. Short-term losses mean little to him because Aulas reckons that in the long-term there is rationality, even to football. His rationale is simple. If you buy good players for less than they are worth, you will win more games. You will then have more money to buy better players for less than what they are worth. The better players will then win you bigger games and so on. Of course all this is easier said than done, but Lyon's track record is impeccable. They continue to triumph based on these principles. Lyon hardly overpays for players and instead is known as the best wheeler-dealers in the business. They know when to buy a player and when to sell him. And often most of the players they sell are not as successful in their next clubs, because they also sell at the right time. Michael Essien and Eric Abidal are examples of the former and Mahmadou Diarra and Karim Benzema examples of the latter. Essien and Abidal were sold at massive profits to Chelsea and Barcelona respectively, and both have shone. Diarra and Benzema on the other hand have struggled to replicate their form for Lyon at Madrid. Considering the profile of the players that Lyon has sold over the last decade, you would think they would be languishing in the bottom echelons. But Aulas always has a ready-made replacement and this past season, for the first time, they even cracked the Champions League semifinal. It is easy to put this down to a manager but Lyon have had four to five in the last decade and their results have been roughly similar. It is almost always Aulas' superior dealings that make the difference. In Germany, Werder Bremen is quite similar, but maybe not as successful. Their general manager Klaus Allofs is a master at manipulating talent and finding players at the right time. The Brazilian Diego is a good example. A burgeoning talent, Diego was struggling in his first stint at Europe as a teenager. Porto had relegated him to their B team and his talent was rotting. But Allofs stepped in, buying him for about 6 million pounds. A Bundesliga title and UEFA Cup final later, Bremen sold him on to Juventus for 20 million pounds. Both Lyon and Bremen work under similar premises and avoid the pitfalls mentioned earlier. They never overpay for a player or buy him on the basis of success at a big tournament. New managers hardly have a say in transfer dealings, in Lyon's case, while Bremen have had the same manager for more than a decade. They hardly ever buy players in vogue and even when they do; it's almost always one who is undervalued. Juninho Pernambucano is a Brazilian and a Lyon legend, but he was picked up at a pittance, similar to Diego and served the club very well. But most importantly both clubs always know exactly the right time to sell a player. Mesut Oezil arrived from Schalke for about 3 million pounds and was sold for five times that. Next season he would have left for free and Bremen's model might have been affected. In the end though, it is worth remembering that clubs like Bremen and Lyon can only exist under such a system because their supporters are more understanding than your usual Madrid or Manchester lot. But suffice to say, we need more clubs like this, because otherwise, football would be a boring game restricted to a group of elitists. And no one wants that fate for the beautiful game. Quazi Zulquarnain Islam is a football Journalist.

|