Inside

|

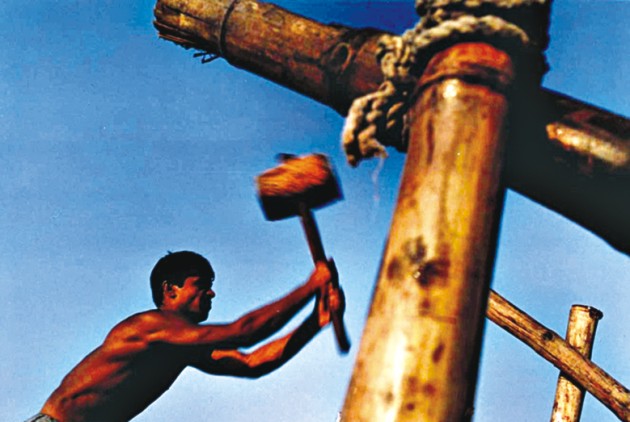

A Triangular Manipulation MD. SHAIRUL MASHREQUE looks into the politics of rural development

The contemporary scenario of triangular manipulation is a manipulation by the dominant interest group -- the coalition of interests among "governing elites," "fortune seeking political entrepreneurs" and privileged business communities. Governing elites include both political leadership and bureaucracy. It is seen that governing elites expand various opportunities for economic concentration including rent-seeking ones. It ultimately aggravates the poverty situation threatening the legitimacy of the regime and increasing the probability of regime turn over. Political leadership actually does not represent the majority of the rural population. The change of political allegiance of local leadership with the change of the ruling regime is evident (Ahmed 1991). Local leadership has turned into a lucrative trade without investment drawing most patronage resources from the ruling regimes. Patronage resources have been usually placed at the disposal of the influential elites including local MPs. There is a great struggle among faction leaders to capture those resources which provide accessibility to development inputs flowing into the locality from different strategic points of the "centre power axis." The crisis of non-participation of the ordinary ruralities is crystal clear in a "soft" and "predatory" state like Bangladesh. Here the structure of governance is subservient to "extensive rent seeking" an omnipresent policy to obtain private benefits from public actions and resources. So fuzzy governance bedevils the otherwise seemingly stable community life. Repeated policy failure is thus a forgone conclusion. This is evident from the frantic attempt of the governing elites to grab more resources. Bureaucracy is found to be bolstering fuzzy local governance using manipulative skills and techniques. The governing class including the tycoons may not benefit from the "enforcement of rules of law," transparency and anti-corruption state action. Instead they "gain from extensive unproductive and profit seeking activities in a political system they control than from long term efforts to build a well functioning state in which economic progress and democratic institutions flourish"(Nafgee and Anvize:2002). The protracted fuzzy governance is an inevitable outcome of triangular manipulation with bureaucracy going strong to practice corruption. A plethora of organisations influenced by a triangular alliance are not effective mechanisms to articulate the interest of the deprived class as policy inputs. Local government bodies, co-operatives, several committees and civil societies (not all) have become more or less the "ploys of intensive political hobnobbing." The foundation of peasant existence in the politico-administrative landscape has been constantly eroded by three interlinked processes: one operates on the global dimension, one the national plane and one at the local level. The net effects of the cold and dark happenings in the globalisation process have been disastrous in the southern hemisphere; battering the lives of peasants. The cumulative effects of policy failures and inadequacies in organisa-tion and management at the national level are equally disastrous, worsening material conditions of living. In addition, the shattering impact of project intervention altogether with flimsy and insensitive institutional structures on the peasant economy is obvious. Policy failure is not a matter of inefficient public policy but clear-cut fuzzy governance. The governing class running the show through various intervening interest groups blissfully overlooks progressive impoverishment in the countryside marked by a "veritable" cauldron of economic crises. The downslide of the poor and fixed income group has become one of the significant marks of the fall on the destiny of the peasant society. This state of affairs has accelerated by the dysfunction of politico-bureaucratic leadership at the local level. Local government, including field administration and local self-governing body, has been serving the "centre power axis" consisting of political leaders, bureaucracy and metropolitan tycoons. Trapped by the illusion of autonomy, the continuing malfunctioning of local governance tells heavily on community life terribly immersing the peasant and low-income group. There are many cases of corruption practiced by public officials in collaboration with politicians who have lost public image. We may cite one case of bureaucratic corruption: misappropriation of food from buffer stock. Buffer stock operations to maintain price stabilisation of food items in internal markets and to meet sticky situations such as food crisis were soaked with misappropriation. This corrupt practice is proverbial Food crisis loomed large in 2006. But the ruling politicians and bureaucrats unashamedly claimed there was no such crisis. Tactics of misappropriation that are at bureaucrats' fingertips also benefited the ministers. Food otherwise misappropriated was shown as a consignment on the way to a delivery point. Out of 603,852 metric tons of food in buffer stock 201,204 metric tons of food was shown as consignment on the way. Stories about sinking a barge with food in the river/sea and missing of truckloads of cereal are common and misleading. In reality food items were misappropriated (Bangladesh Observer, April 4, 2006). At the local level of rural development, village leaders branded as touts benefited from bureaucratic allocation that turned into misappropriation and bungling. This is evidenced from manifold stories of malpractice in public distribution system as in the case of subsidies in agriculture (fertiliser as a case), distribution of khas (government-owned) land, relief under Food for Works Programmes (FWP) and Money for Works Programmes (MWP), rural rationing and Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGD). The wave of politicisation -- a phenomenon of the recent past has its impact on the criminalisation of local politics. Politicisation in the whirlpool of criminalisation of politics took a heavy toll. The unholy nexus between the politician, politicised local bureaucrats and businessmen was embedded into the governing structure to pollute policy environment at the local point. Politicisation of administration constituted a fundamental constraint to fairness in justice and distribution of inputs and to new investment by bonafide businessmen. It rather facilitates political and bureaucratic payoffs for the privilege of doing businesses. Reports have it that artificial crisis of food and price hikes are due to the presence of criminal syndicates controlling markets at bottom. This sort of political bankruptcy adversely affects the peripheries. The terribly bad shaped democratic institutions plagued by internal strife, impotence and splits enable the bureaucracy to gain a stranglehold over local institutions. Relative autonomy is used only to resolve internal contradictions and manage manifold crises in intriguing issues of development to serve information needs about local situation. As a matter of fact the recent dynamics of rural development under bureaucratically shaped institutional arrangement hints much about erratic governance. While "bureau-pathology," "organised anarchy" and "formalism" at the field are a constant source of discomfort to the ordinary masses, the local conglomerates feel at home on the vantage point of access relationship. The dysfunctional role of local MPs is pertinent to the analysis of mal-administration. They have been found using their position to channel rural development projects into their constituency. It is obviously to establish command over patronage resources and mobilising supports. One can easily surmise the direction of local politics of rural development that is presumed to be inhibiting normative process of project implementation.

The urge to share patronage resources was found to be a critical factor in the abiding interests of MPs to see how projects were being implemented. MPs increasingly intruded into local politics when it came to utilisation of public funds in their respective constituencies. Since the abolition of upazila (sub-district), local administration in 1991 the MPs emerged as the major players in local politics of rural development to control public resource patronage. Such intervention impinges on the institution of local government giving rise to dualism in the implementation of the projects of rural development. Anyway, the rural leaders affiliated to ruling party and politicised local bureaucrats were not presumed to be resentful. They might not be affected by the centrally determined sectoral allocations of development projects. Increasing alienation of the "disadvantaged locus" is thus an inevitable outcome of the malfunctioning of the structural dimension of governance based on triangular manipulation. The bureaucratic approach is deeply entrenched with a rigid blueprint and non-participation. Political leadership is soaked with marked populism, factionalism and power politics. Economically affluent tycoons approach with the proceeds of business somewhat in a non-conventional manner to influence politics and public policies in their favour. This triangular manipulation contributes much to the reinforcement of "institutional anarchy." Protest movement against irregularities, price hike, malpractice, insensitive political leadership and much less bureaucratic response -- institutional anarchy syndrome -- creates sufficient ground for a man-made crisis. Structural tension has become a common feature of community life at the base. Unhappy consequences of even disadvantaged-focused rural development projects breed frustration among the disgruntled and the victims. This is a continuing process as the bottom end of distribution profile continues to be caught up by the deprivation trap. Paradoxically the outcomes of poverty alleviation policy in the presence of policy triangles rather help the crisis of poverty to raise its ugly head. Allocative decisions under elitist manipulation both intra and intersect orally without emphasising the depressed rural sector and isolated population in the countryside, may mean to exclude the rural poor from the purview. Pro-poor economic growth with targeted safety-nets as envisioned in the PRSP is mere rhetoric. Moreover the extent and ramifications of rural poverty can hardly be reduced to a single dimension of political economy -- income, material benefits, maternity health, and reduced infant mortality. There are other dimensions too like community organisation, market mechanisms and bureaucratic public administration. The inextricable crisis of rural poverty that badly hurts the countryside is a culmination of erratic policy management that perpetuates discrimination and instability, Project implementation scenario bespeaks of the poverty of implementation resulting in a series of policy failures. Several policy induced measures funded by donors and manipulated by policy triangles are stated to be counterproductive having failed to increase the poor's access to "productive assets," "raise their return to assets," improve employment situation during lean period, ensuring the poor's access to basic education and health and supplement their resources with transfer as "access to secondary incomes." Too many projects under annual development programme (ADP) and several technical assistance programmes and technology transfers have been far from effective, weakening the platform of stabilisation and integration. Multiplicity of anti-poverty projects is merely a stop-a-gap measure to compensate for the colossal damage done to the agro-based peasant economy due to large-scale privatisation under open market economy. 'The primary producers of rice, wheat, cotton, and jute are beginning to face challenge; in market-led "institutional milieu." They defray excessive costs of production getting much less return than expected. Land owning plutocrats, potential investors and tycoons are not affected. This economic class can easily shift to even tertiary occupations making best use of opportunities under privatisation (Mashreque 2005). Projected safety nets against damaging consequences of globalisation can hardly provide protection against exorbitant rate of interests, black marketing, hording and ills of monopoly competition. There is no protection for cooperative marketing. It is facing problems such as inadequate facilities for transportation, poor holding power of the peasants, storage of facilities, lack of grading and standardisation, fraud practice, lack of primary producer's organisation and inadequate market intelligence (Habibullah 2005). In addition, there is no protection against local monopoly of business class and dealers and middlemen obtaining support from politico-administrative institution and no arrangement for the extension of market infrastructures to the benefit of the primary producers of rice, cereals and cash crops. The dichotomous situation in the policy arena of rural development as clearly indicated by relational matrix and uneven distributional profile stands out to be a menacing setback bringing us to the heart of political economy of peasant society in Bangladesh. The challenge in the wake of the downward spiral of rural poverty and escalating tension can hardly be met even by pro-poor economic growth with a human face. The institutional set-ups as the vehicle of triangular manipulation cannot be expected to provide a tangible program for the poor. The strategies of rural development to handle outstanding issues accelerate poverty aggravation rather than alleviation reportedly at the implementation stage due largely to a subtle mechanism of manipulation engineered by "policy triangles." There has been overlapping of the ruling elites in all decision making institutions at he micro level, for example, village council, co-operative, union parishad and various development and project committees. They decide upon priorities and strategies maintaining liaison with local bureaucracy that is dispensing promotional and extension services. In the process of triangular manipulation they obtain access to patronage resources.

Roadmap to poverty alleviation -- the projected policy goal sketched by the governing class has turned into a roadmap to manipulation and corruption. The real beneficiaries are not the poor as such. Leaders/tycoons dispense patronage resources to their immediate followers and henchmen. As a result benefits of growth-oriented development trickle down only to the immediate followers. Bona fide participation in the sharing of benefits has evaporated in such a policy environment. The cumulative understanding of the peasant society from a series of research activities is not enough to see things below the surface. Ignorance about the behind-the-scenes maneuvers continues to be profound despite much concern in development policy with crisis of poverty. The content of public policy on poverty alleviation prepared through agenda seeking activities of the relevant institutions blocks the road to desired outcomes. For, there is little knowledge about policy context, environment matters, resource relevant activities, interest groups, target population, social fabric and organisational resources. True, there remains a critical linkage between policy content and policy context. An attempt to understand this critical linkage in rural landscape enables us to fathom various structural features that are synergistically related to provide a background of grinding poverty. The economically and politically influential have overtime developed all the skills of manipulation bending the process of policy implementation in their favour in alliance with the bureaucracy. They fare well in the competition for scarce valuables in an economic environment that the bureaucrats pretend to change under the banner of poverty alleviation. Despite a barrage of policy measures to redress public predicament at the rural-local point the overall context reveal that such measures have paradoxically reinforced the status-quo empowering the dominant peasant layer. Bureaucratic power is hardly used to curb the stranglehold of the landowning and rising commercial classes. The governing class is thus reluctant to go for any economic policy reforms that may cost them "political support without bringing any political dividend." The members of the governing class are understandably bound by common interest that ultimately coheres a well-knit relationship. They thus form "special understanding" as a class for itself to successfully block any effort that threatens their interest (Mozumder 1994). Any apparent conflict/competition on any development issue among the ruling elites is a mere camouflage to turn public attention other way round. Under circumstances it seems difficult for the incumbents on the supply side to break the "political vicious circle" protecting the rights of the peasants through projected safety nets against the domineering political and economic forces. When such forces coalesce to render distribution process all but skewed market as a socially construed mechanism functions to drain the surplus from the rural to the metropolitan area. A similar situation exits in India where sweeping changes of the social action by action from above were thrown away despite repeated ideological assertions of the policy makers for developing socialistic pattern of economy. This is due largely to the lack of explicit political commitment and the domination of the propertied class over political leadership. Elitist orientation of bureaucracy with its close linkage with local elite accounts much for making things worse. On the one hand the hidden subsidies on food and other inputs are phased out in rural Bangladesh. On the other hand, a major percentage of aid funds earmarked for poverty alleviation is absorbed in paying high salary to project consultants-both local and foreign and defraying the cost of contracting the project/sub-project through an underhand deal with bureaucratic incumbents. Only a little percentage is spent on the target beneficiaries. Dr. Md. Shairul Mashreque is a Professor, Department of Public Administration, Chittagong University.

|